Monica Amor

Monica Amor

Organs and needles: twenty-five years after his death, the Brazilian artist receives his first US solo show.

José Leonilson: Empty Man, installation view. Image courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas.

José Leonilson: Empty Man, Americas Society / Council of the Americas, 680 Park Avenue, New York City, through February 3, 2018

• • •

This carefully curated exhibition of the Brazilian artist José Leonilson (1957–93) presents a body of work that is intensely poetic, intimate, and materially fragile. Those familiar with contemporary Latin American art know Leonilson best for his delicate embroideries featuring images and texts that elusively ponder a range of existential issues, including the nature of the self, the possibility of signification, and the emotional life of the body. Empty Man (as the show is titled, after a work by the artist) delves deeply into this deceptively marginal practice. His first solo exhibition in the United States, it introduces Leonilson to a US audience through approximately fifty drawings, paintings, and, of course, embroideries, housed in the Americas Society’s three-room gallery space.

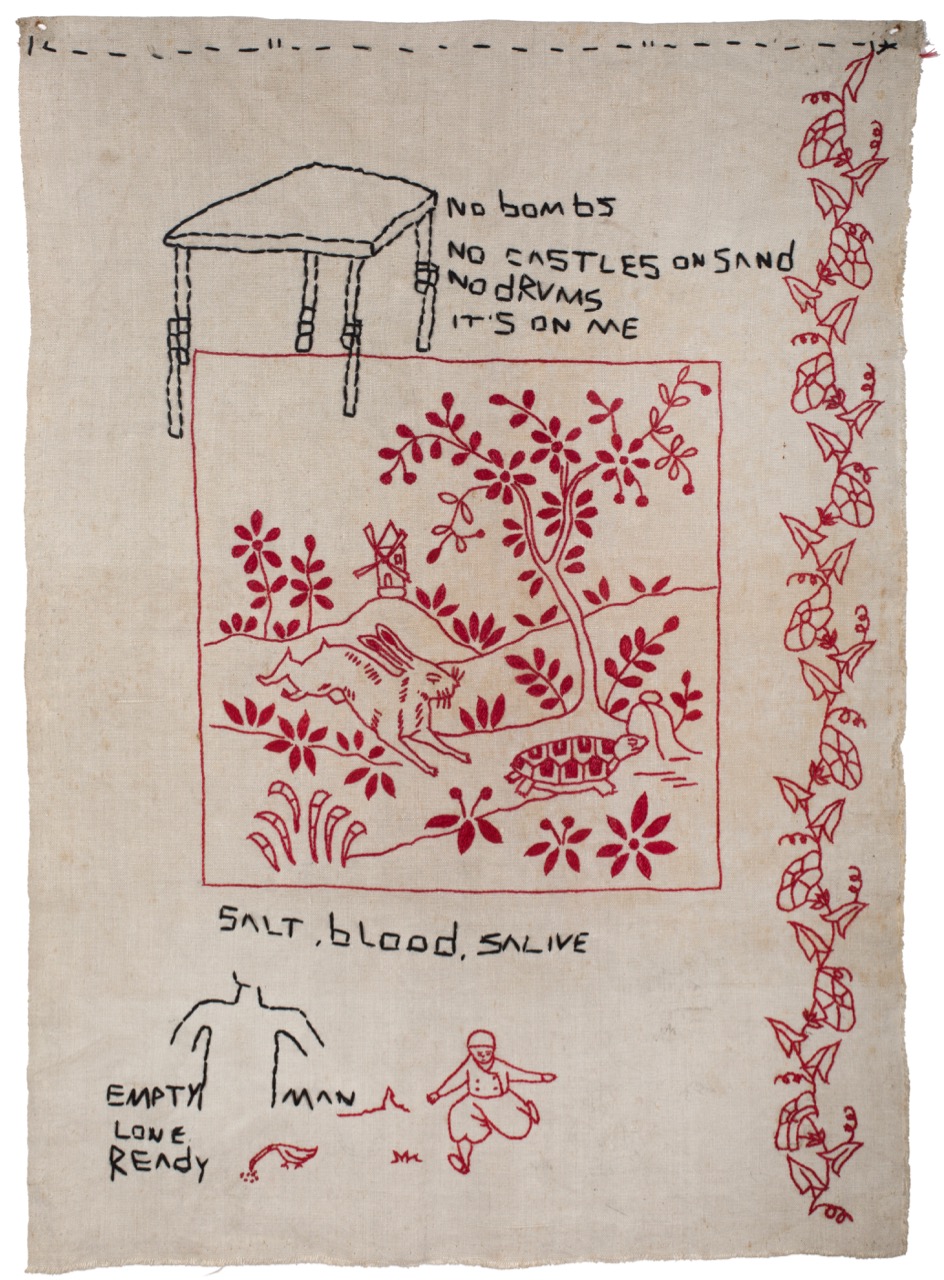

José Leonilson, Empty man, 1991. Thread on embroidered linen, 20 ⅞ × 14 9⁄16 inches. © Projeto Leonilson. Photo: Rubens Chiri.

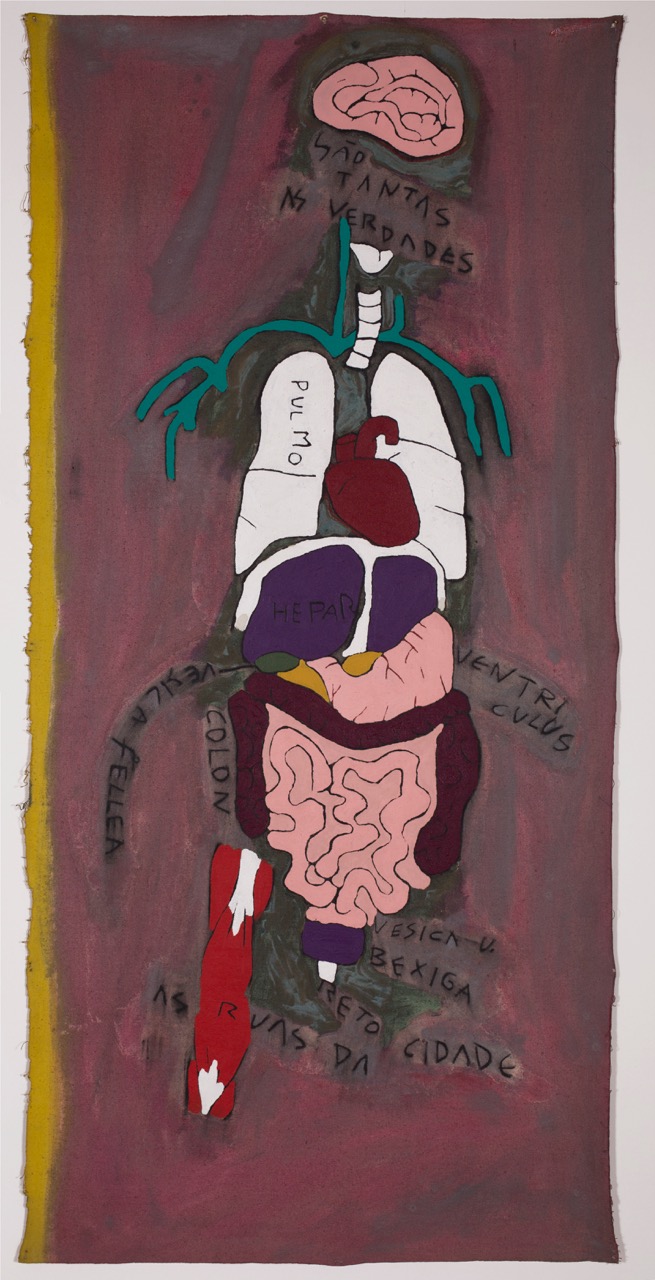

At the outset of his career, Leonilson was part of a group of artists deeply invested in the medium of painting as a form of expression. Empty Man, however, focuses on the shift from painting to needlework that roughly coincided with Leonilson’s HIV diagnosis in 1991. To emphasize the importance of this later phase of the artist’s career, the curators have organized Empty Man in reverse chronological order, presenting his embroideries first. I began in the last room, though, where I encountered The City Streets (c. 1988). One of the earliest pieces in the show, the painting is revelatory and presages things to come. Employing acrylic on unstretched canvas, Leonilson depicts a body’s internal organs floating over an unevenly painted surface of purple and pink flanked, on the left, by a thin band of yellow. Lacking the graphic exactitude of its medical counterpart, the picture incorporates a number of hand-written labels: lung, colon, bladder, rectum. It also inserts two non-referential sentences: “So many are the truths” (inscribed between the images of brain and tongue) and “The city streets” (found at the bottom of the painting, right below the anus and digestive tract). We may associate “truths” with the realm of thought and speech and “city streets” with the more mundane realm of bodily functions, but the meaning of these words remains elusive. Moreover, this body lacks a boundary, a graphic line that could contain these organs, that would give human form to this conglomerate of body parts. And this affront on proper form informs much of the work that we see here.

José Leonilson, As ruas da cidade (The City Streets), c. 1988. Acrylic paint on unstretched canvas, 78 ¾ × 37 ⅜ inches. © Projeto Leonilson. Photo: Rubens Chiri.

The other paintings on display in the final gallery echo the style and concerns of The City Streets. Unstretched canvases tacked directly to the wall feature simplified images, often with enigmatic words and phrases, set against monochrome grounds. Many engage and unravel the logic of conceptual systems, as exemplified in numbers, maps, and so forth. The artist mixes the inside with the outside: organs with streets, rivers with brains, hearts with kingdoms. The self is not represented, rather it is scattered throughout the world.

José Leonilson, Cidades europeias com botões e escudos (European Cities with Buttons and Shields), 1988. Acrylic paint, colored pencil, thread, and buttons on unstretched canvas, 14 1⁄16 × 25 × ⅜ inches. © Projeto Leonilson. Photo: Edouard Fraipont.

A second key work in this gallery, also from 1988, shows Leonilson beginning to explore needlework. Titled European Cities with Buttons and Shields, it includes buttons of various sizes and colors randomly placed across the surface of an unstretched canvas along with the clumsily written names of cities that the artist had visited in Spain, Germany, Italy, Holland, Switzerland. This bespeaks a fascination with traveling, wandering, and internationalism that is addressed in the show’s accompanying catalogue. (As it happens, Leonilson received a diploma from the School of Tourism of Baleares, Spain, in 1976). Most importantly, though, along the perimeter of the work, the artist stitched a frame of thread that acts as a kind of surrogate for the painterly one. Through this piercing of the surface, Leonilson appropriates a “minor” art, a craft historically associated with feminine work, to call the grand narrative of painting into question, just as his simplified images and syntax-less words undermine the notion of straightforward representation.

José Leonilson: Empty Man, installation view. Image courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas.

As can be seen in the work displayed in the other two galleries (mostly embroideries and drawings), the artist increasingly employed panels of voile, silk, velvet, felt, cotton, and linen. These delicate fabrics replaced canvas, painting’s traditional support. Leonilson’s challenge to the conventions of brushstroke and drawing (as color and line coalesce in the stitch) is thus further advanced by his experimentation with the works’ material support. Scale is also relevant here. Upending the monumentality of much 1980s painting, Leonilson created intimate works suited to the rhythmic gesture of stitching and the detailed quality commonly associated with decorative arts. (Extending this link, several pieces feature crystals, shiny buttons, colorful stones, lace, and beads.)

José Leonilson, Cheio, vazio (Full, Empty), 1992. Thread on voile and striped cotton fabric, 21 ¼ × 19 5⁄16 inches. © Projeto Leonilson. Photo: Edouard Fraipont.

Some of the most powerful works in the show are a group of sparse, text-based embroideries that resonate with the title of the exhibition, which suggests a certain lack, a certain dispersal. In these image-less works, Leonilson intensifies the indeterminacy of both language and self that marks his early painting: the meaning of words can never be fully gathered, and “man” is an empty vessel to be filled by his contingent encounters with the world. In Full, Empty (1992)—four panels of green-striped, orange, white, and yellow fabric, each featuring either the word “full” (cheio) or the word “empty” (vazio)—Leonilson approaches the prospect of lack through an ambivalent oscillation of opposing terms.

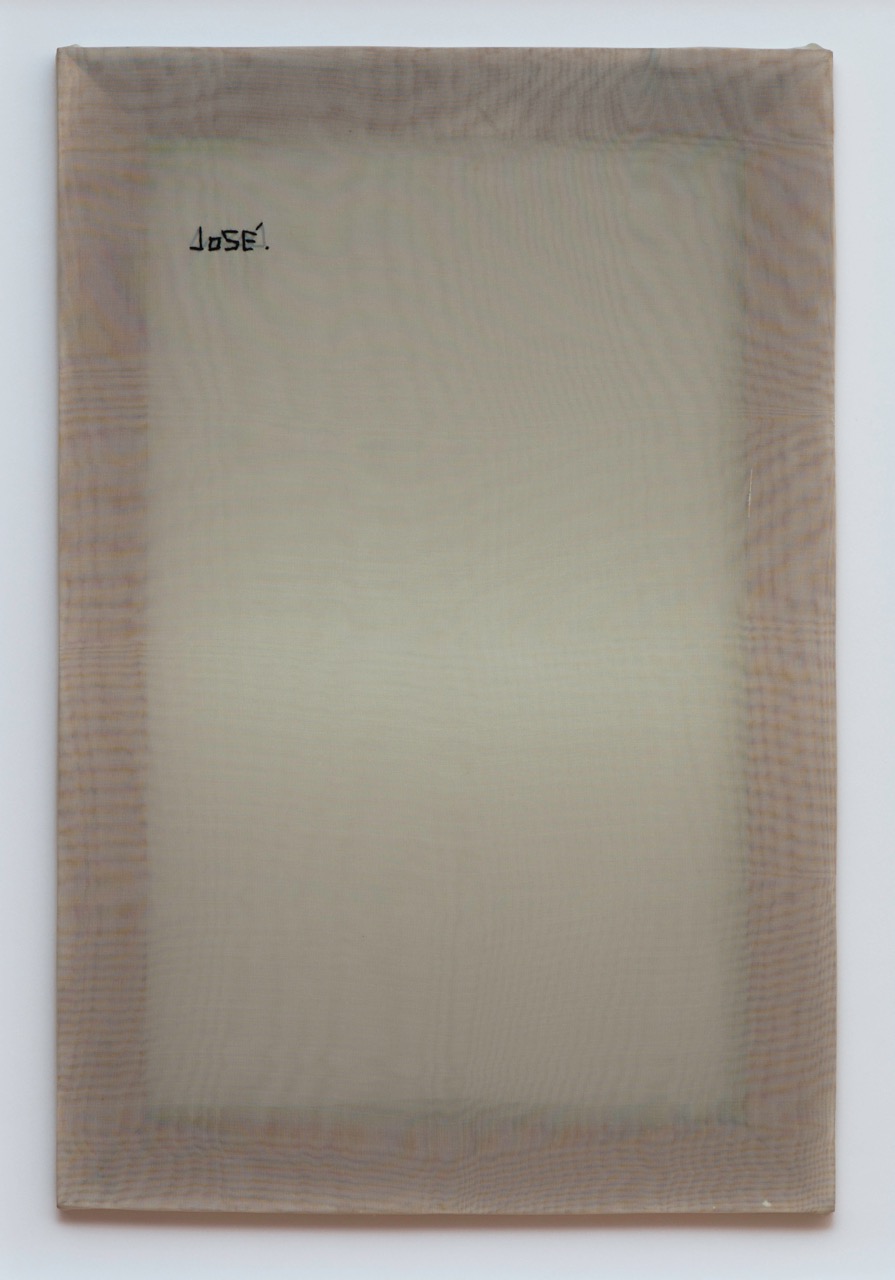

José Leonilson, José, 1991. Thread on voile, 23 ⅝ × 15 ¾ inches. © Projecto Leonilson. Photo: Edouard Fraipont.

José (1991), consisting simply of delicate voile stretched over a wooden frame and the first name of the artist stitched with black thread on the upper-left corner, explores emptiness in another guise. Although the reflective quality of the fabric evokes a mirror, this surface does not present a figurative self-portrait. It contains only the “empty” word that every name is—until it is attached to a someone.

Created two years before the artist’s death from AIDS, 34 with Scars (1991) acts as a sort of manifesto on all of the above: the fluctuation of meaning, emptiness, image-less/formless self-representation, and the substitution of brushwork with stitch. Over a surface of white fabric, with black thread sewn along its border, Leonilson has inserted two elements. On the upper right side is the number 34 (his age at the time)—a lapidary, utterly unexpressive allusion to the self in the face of the total silence that awaited the terminally ill artist. On the left side, in the middle ground, two rows of crisscrossed stitches hover like scars. The stitch is both an abstract mark and a pictorial element that here transforms the white fabric into a field of flesh. Of course, stitching is almost a mechanical gesture, an in and out used in sewing, embroidery, and suture. And thus, with this one work, Leonilson seems to reject expressive brushwork and line, now replaced by a piercing of the work’s surface and the wounded body.

Monica Amor is a professor of modern and contemporary art at the Maryland Institute College of Art. She is the author of Theories of the Nonobject: Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, 1944–1969 (University of California Press, 2016) and is currently writing on Philippe Parreno’s work. Her next book project is entitled Gego: Weaving the Space In-Between.