George Baker

George Baker

Mark Alice Durant steps through the “photographic window” in his autobiographical book.

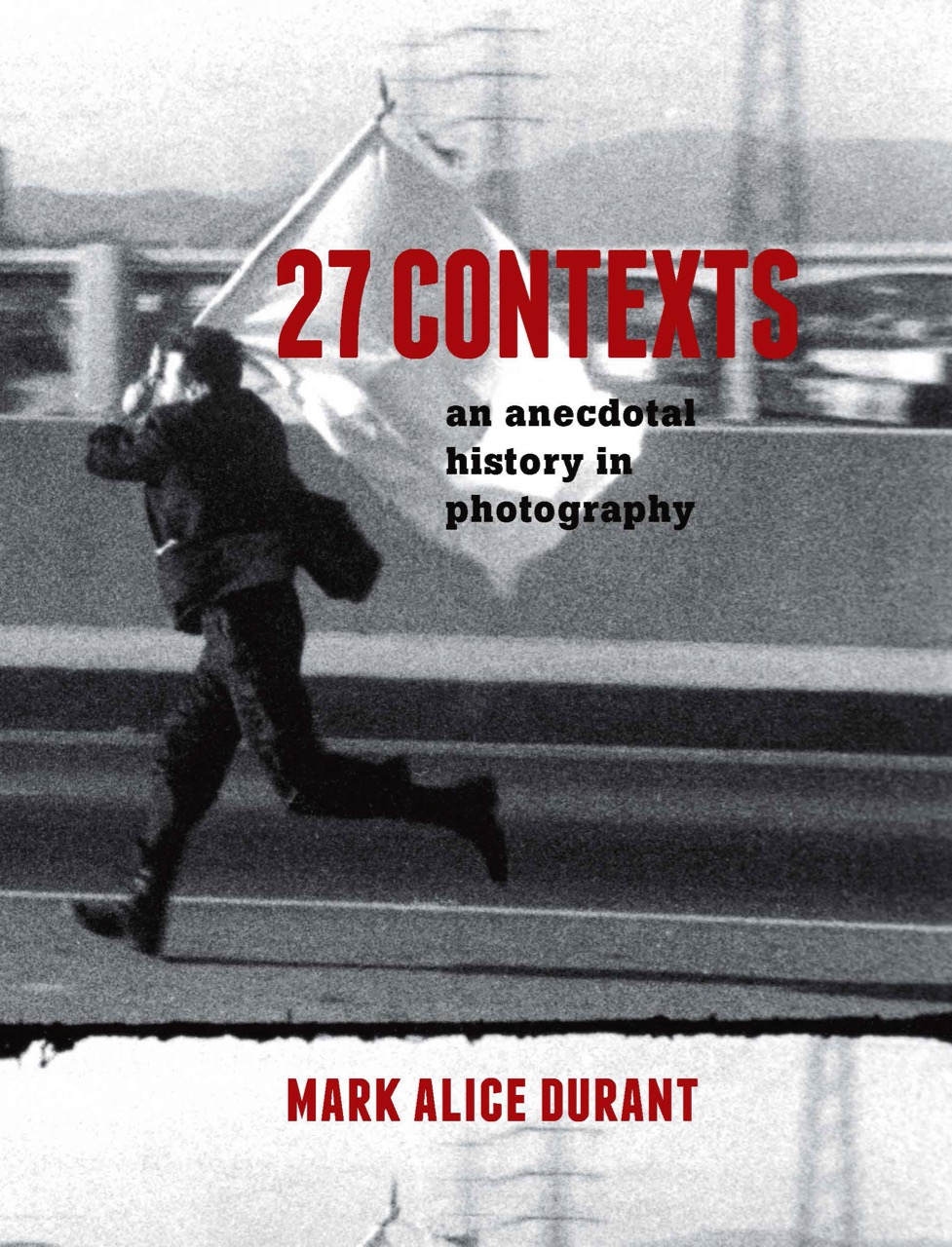

27 Contexts: An Anecdotal History in Photography, by Mark Alice Durant, Saint Lucy Books, 285 pages, $39.95

• • •

I will read each and every book that comes my way having to do with photography—it doesn’t matter whether the writer is an art historian, or a novelist, or a philosopher. One is always looking for that book on photography, the one that will upend the sinking feeling that there really is only one book on photography, Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. We are all tired of our monogamy. We want to fall in love again.

Lately, the only contenders for me have been photographers writing on photography, or photographer writers, a strange and compelling through line in the history of the medium, from failed avant-garde novelist Walker Evans to excessive diarist Edward Weston. The photographer writer has returned with a vengeance—I am thinking of artists like Zoe Leonard or Moyra Davey. The case of Mark Alice Durant seems a little different, perhaps more extreme, for he is an artist and a teacher recognized now primarily for his writing, and for a website, saint-lucy.com, devoted to texts on photography and contemporary art.

27 Contexts brings together many short-form articles that previously appeared on Durant’s website, or as eccentric catalog and magazine essays. The title immediately raises a question: Why “contexts”? The photograph needs contexts, Durant informs us, in an essay on his teacher Larry Sultan. “Fixed as they appear to be,” he writes, “photographs are unstable and contingent on context to fulfill their utility.” Speaking of the dislocated found photographs in Sultan’s series entitled Evidence, Durant describes what might be seen as the countertype of his own project: “The simple act of prying [photographs] from their contexts creates surrealist puzzles. They point, as all photographs do, but we cannot understand what they are pointing at.”

The title also tells us the book is not a history “of” photography, but rather “in” it. Durant’s book is closer to autobiography, a kind of memoir, than a treatise on the photograph. Its short chapters travel in roughshod chronological order, from Durant’s working-class Boston Irish childhood to his artistic awakening, from formative European and Latin American travels to his shattering midlife crisis, culminating in Durant’s current existence in Baltimore. Photographs abound, the occasion for almost every individual “texticle” (an appropriate Duchampian term)—words spin out from family photo albums, personal snapshots, and anonymous found images; documentary and photojournalism; art photography by the likes of Josef Koudelka or Nan Goldin; many more photographs by Durant himself; album cover art and Playboy centerfolds; spirit photography and images of the cosmos made by the Hubble telescope.

Durant’s writing—his storytelling—is often thrilling, wrenching, beautiful, especially at the book’s beginning, as the author lingers over photographs that stir the nostalgic mists of childhood memory, and at its end, as he confronts in more essayistic texts larger cultural problems and some crucial artistic predecessors. (There is a great chapter on the late work of Chris Marker.) Writing is also one of the key lessons of the book, which might be read as proposing a non-expository, performed theory of the photograph and its ties to language.

Like the mute images in Sultan’s Evidence series, Durant repeatedly wants the photograph to loosen itself from its original context—from its own history, or even, more generally, from the photograph’s vaunted tie to the past. But this is so that photography might then serve as a future-oriented platform for language, or what Durant calls a “foundation for a new narrative.” In one chapter Durant considers photographs found after the dispersal of a Midwestern tornado, and offers up a torrent of words in the face of their catastrophic dislocation; in another, he stages images whose depicted events never actually occurred, in the hopes of convincing another writer to fall in love with him, the photograph as “passport” to potential “future stories of a life genuinely lived.”

In a key early passage in the book, Durant looks back, to photographs left to him by his father, taken during the Korean War. “I inherited little from my father aside from dark hair, small hands, a predisposition to alcohol,” Durant confesses. He fantasizes through words a kind of entrance into the image itself, a sudden photographic intimacy: “The more distant [my father] became at home, the harder I studied those pictures, as if I might be able to pass through the membrane of time and discover a path in the photographs’ silvery grain; as if I might follow and find him with arms open, smiling back at his future son.” Two tropes emerge in this passage that everywhere haunt Durant’s description of other photographs. First, Durant inherits these photographs like he does his father’s “dark hair,” and an obsession with hair recurs throughout the memoir. It is the subject of one of the most charming chapters, “Beatles’ Haircuts,” where Young Durant both adulates and fears the self-styling of the hirsute band, while going through his own adolescent transformation, desperately pushing at the roots of his newborn facial hairs to “return them below, to the unknowable darkness from whence they came.” He eventually falls in love with a woman “solely because she had hair like Maya [Deren].” Always in metamorphosis, simultaneously living and yet dead, hair works here as a central metaphor of the photograph.

This metaphor is echoed by Durant’s repeated telling of his habit of folding up his favorite photographs, to press them close to his body like a second skin, inserting them into his wallet, pinning them up to the bookcase next to his bed, giving in to what he consistently calls the photograph’s “gravitational pull.” Finding a trove of Playboys early on, Young Durant and his friends slip the centerfold images under their shirts, “so [the nudes] might kiss our smooth torsos.” They run them out to a garage, sliding the pictures behind chicken wire so that they might “stand upright on the windowsill.” Durant’s endless opening up (his enlivening) of photographs by writing seems analogized by his treatment of the photograph as a quasi-living thing, the animist dream of the young boys and their “still-innocent penises.”

The climactic instance of this dynamic arrives in the incandescent chapter Durant devotes to filmmaker Maya Deren. It was her photograph that for years stared down at his bed, and in it Durant looks closely again, of course, at her hair, “wet, ropey, and dark.” As with his father’s photographs, Durant relates another attempt to “try to push beyond the transparent barrier, the hard and shiny surface of the photograph,” to “slip through the emulsion and pass through the skin between us.” In words almost parodically sexual, the writer informs us that “the photograph resists, and then like the surface of a soap bubble it relents, temporarily parting as I slide in, followed by a little whoosh as it closes seamlessly behind me.” We now understand what a history “in” photographs might actually mean, for Durant. It is words, writing, the necessary “fantasy” of “a narrative,” that provide the communion, and enact the transubstantiation, the bridge into and beyond the object that Durant also describes as the “photographic window.” For we are suddenly and ecstatically “inside” the photograph, repeatedly so, in Durant’s account. Falling in love, again.

George Baker is a co-editor of October magazine, and a frequent critic for publications including Artforum, Aperture, Texte zur Kunst, and frieze. He is completing a book on contemporary photography, entitled Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography, and has recently worked closely with artists Paul Chan and Walead Beshty on their respective books of collected writings. He teaches modern and contemporary art at UCLA.