Eric Banks

Eric Banks

Masochism and swarming ants: a story collection captures the strange violence of writer Taeko Kono.

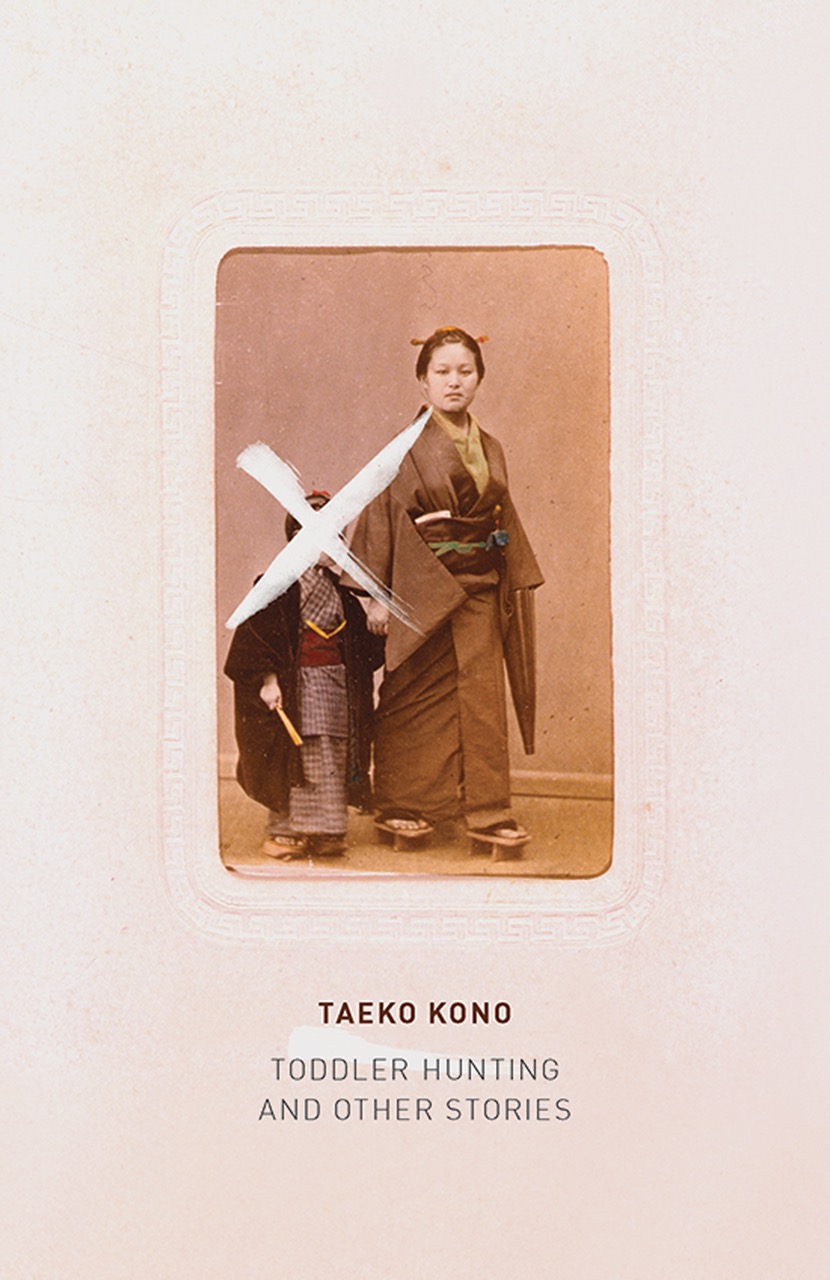

Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories, by Taeko Kono, translated by Lucy North, New Directions, 274 pages, $16.95

• • •

I like to imagine Taeko Kono and Angela Carter meeting each other in Tokyo at the end of the ’60s, after Carter had fled a flaccid marriage and become a participant-observer of the sexual revolution, at one point even working at a horrible hostess bar, the “front line,” as she put it, in the war of men against women. They would have had a lot to talk about, from their idiosyncratic feminism to the odd complementarity of Carter’s fascination with Sade and Kono’s deep investment in masochism, which figures spectacularly in nearly all of her stories. Not long before the time this fantasy meeting would have taken place, Deleuze had famously disputed the idea that the two practices—sadism and masochism—were obverses of each other, as Freud thought, with masochism merely the passive flip side of the sadist coin. Still, in both sadism and masochism, as in Carter’s and Kono’s work, pleasure and pain sit menacingly near.

Most readers would respond, Taeko who? She ought to be better known, and in Japan, she is. Beginning with the 1961 story that lends the “new” collection Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories its title, the Osaka-born Kono (1926–2015) established herself there as one of the most radically talented authors of her generation, a writer’s writer whose often épater work was hailed for its spark and originality by figures as unlike her as Kenzaburo Oe and Shusaku Endo. Yet Kono remains largely undiscovered in the States, and this despite the publication twenty-two years ago of her work in a New Directions selection nearly identical to the one that is now being released, in elegant translations mostly by Lucy North. More than five decades after they were written, these stories retain their startling punch—none more so than the disturbing titular tale “Toddler-Hunting,” whose main character, a failed opera singer named Akiko, balances her love affair with a like-minded enthusiast of dangerously rough sex and her bizarre obsession with the ill-fitting garments she buys for the little boys she fetishizes.

The even-handedness of Kono’s language—at least in North’s translation—is often as startling as the tales she narrates: “Drawn by the charm of little boys’ clothes, and especially by the scenes to which they gave rise in her mind, Akiko had several times ended up buying something—a pair of reversible shorts with brick-colored cuffs; a deerstalker cap of white terry cloth with a tiny pale maroon check; a miniature pea jacket about a foot and a half high. When she’d purchased something, she would seek out a woman friend with a toddler to dress. Once she’d settled on her prey, she would set out to bestow her gift. . . . The people selected to receive her gifts would be dumbfounded.”

Like the other obsessive characters in many of Kono’s stories, Akiko is at once repellent and credible, and she draws the reader into a fantasy world that feels spun out of a real one in mysterious but damning ways. From story to story Kono’s mostly female subjects go in and out of fugal states of imagined violence, or abruptly find themselves hostage to childhood memories, or shake themselves out of dreams and nightmares. Middle-class and childless, often in recovery from some illness, they inhabit freighted or loveless relationships, like the tubercular housewife on a seaside cure leave from her husband (“Crabs”), or the lawyer and devotee of masochism who worries she is pregnant (“Ants Swarm”), or the opera-goer whose milquetoast husband has decamped to Germany and who now finds herself under the seeming spell of a deformed man and his extravagantly dressed wife (“Theater”).

In “Conjurer” (1967), a confidant of the main character argues that there are “two ways to appreciate magic shows: you either try to figure out how the tricks work, or sit back and enjoy the illusion.” In fact, taken as a whole, read end to end, the ten stories in the volume let the reader have it both ways: “enjoying” the uneasy spectacle of strange violence and only partly resolved suspense, and seeing just how Kono manages to pull off her wizardry. She does so in ways that seem to model her own characters’ barely negotiated, often cracked sense of themselves: subtly modulating between past and present, playing psychological space off the tangible spaces of cramped, tatami-lined rooms, barely lit cemeteries, and crowded train compartments.

Narrative time too is full of switchbacks, often sudden ones, but always subdued. In the marvelous “Snow” (1962), a young woman travels south by train in late January with her partner, their New Year’s vacation postponed by her mother’s death, to escape the snowfall she dreads and that brings with it piercing headaches. With a momentum as inevitable as the train’s, the story ends in a pile of snow, where she begs her partner to bury her alive. Yet “Snow” also obeys a hopscotch pacing, skipping seamlessly back to a sadistic childhood memory of a snowstorm, to her mother’s deathbed, and to a family secret underlying her own off-kilter relationship with time. What’s remarkable about “Snow” is the elegant way Kono threads her treatment of time both formally and conceptually, creating a temporal logic that is at once authorial in nature and fundamentally constitutive of the character.

Suspense—which Deleuze notably argued was a key component of masochism—itself draws on time, especially on the delay of anticipated satisfaction. There is plenty of suspense, delayed and deferred, in Kono’s stories, which nevertheless refuse anything resembling a tidy ending. In fact, she often opts to end her stories with resonant but gnomic parting scenes and strikingly disjointed images, like the “writhing mass” of black insects covering a slice of raw meat that mesmerizes the disturbed lawyer in “Ants Swarm.” The most audaciously inconclusive is “Night Journey” (1963), in which a would-be partner-swapping couple, Fukuko and Murao, travel across town to meet their counterparts but wind up wandering around a ghostly half-built home and a Buddhist graveyard. “Fukuko realized that she’d been in a particular mood for some time now,” the story ends, “a mood that would keep her walking beside Murao into the night, walking on and on until they became the perpetrators—or the victims—of some unpredictable crime.” Here as elsewhere, Kono lets the unresolved hint of violence and culpability dangle—which makes her already beguiling stories all the more charged.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.