Liz Brown

Liz Brown

Night of the Knocking Dead: an investigation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s pursuit of spiritualism.

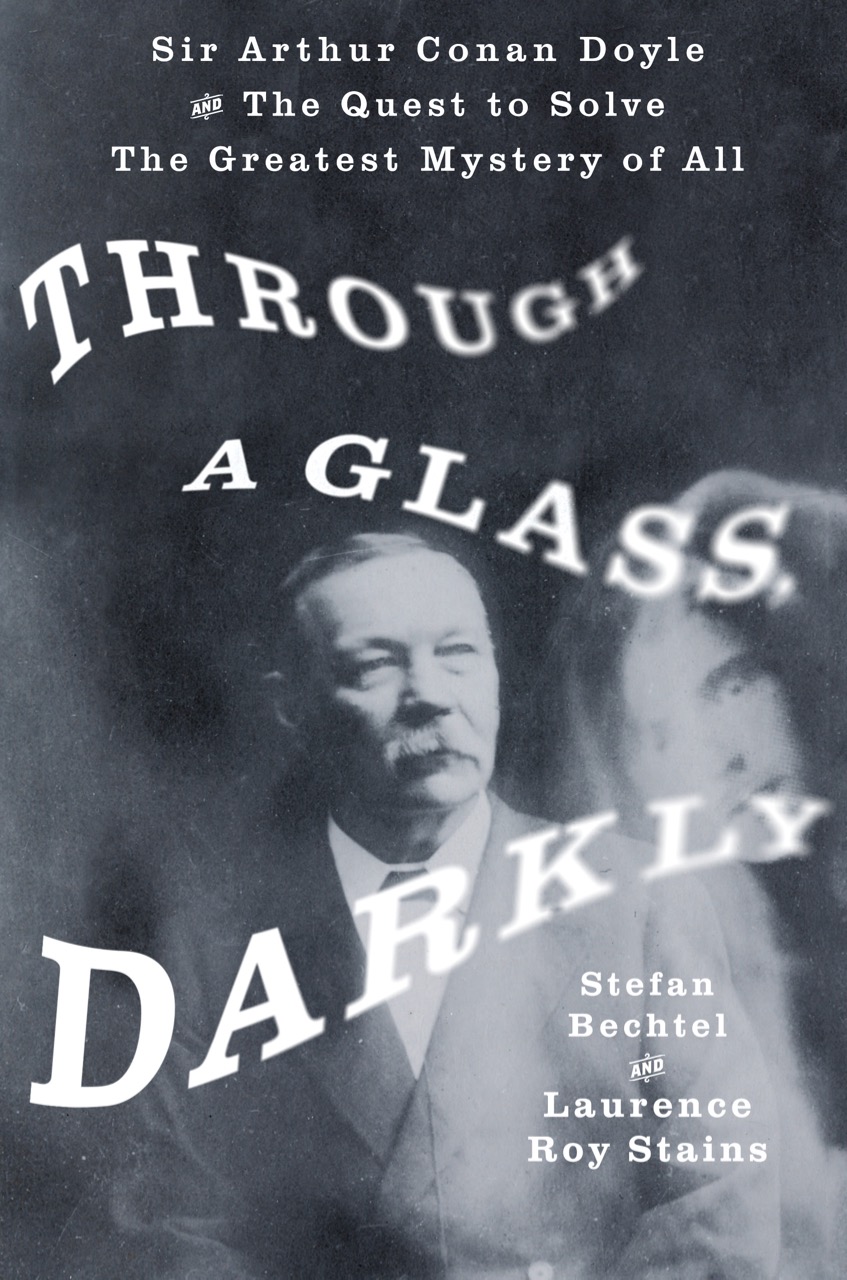

Through a Glass, Darkly: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Quest to Solve the Greatest Mystery of All, by Stefan Bechtel and Laurence Roy Stains, St. Martin’s Press, 303 pages, $26.99

• • •

In 1917, a young girl playing by the side of a stream in the English countryside used her father’s camera to take a photo of herself staring into the lens while five fairies cavorted in the foreground. To the modern eye, Elsie Wright’s snapshot—avant le selfie—is an obvious fake, though many contemporaneous viewers weren’t yet skilled at discerning visual manipulation. Kodak wouldn’t certify the image or any of the others that’d been taken as genuine, but nor did they deny their veracity.

Elsie Wright, The Cottingley Fairies, 1917.

One of the most ardent defenders of the photos’ authenticity was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of perhaps the most famous sleuth of all time. Surely, Sherlock Holmes would’ve questioned the visible stick pin that was holding up the goblin in one of the images, but Doyle had a ready explanation: the protrusion was the creature’s belly button. Mysterious, possibly supernatural phenomena abound, but the Cottingley Fairies, as they came to be known, didn’t fall into that category. Why was Doyle, a serious man trained in medicine who’d invented a character devoted to rational methods of deduction, taken in by such blatant fraud?

In their new book, Through a Glass, Darkly, Stefan Bechtel and Laurence Roy Stains touch on this question as they trace the writer’s conversion to the spiritualist movement. Doyle, who’d grown weary of his celebrated fictional creation, believed his detective stories were a trifling prelude to his life’s real work, which was establishing the scientific truth of spiritualism, “the conviction that those who have passed over had the ability and the desire to make contact across the veil of death with those they’d left behind.”

The movement originated in Hydesville, New York, in 1848 when the Fox family began to hear strange thumps and bumps in their home and their twelve-year-old daughter confronted the inexplicable commotion by tapping her fingers in response. Another daughter joined in and soon a conversation ensued, news spread, the girls gave public demonstrations in auditoriums, and a grassroots phenomenon was born. In the wake of the Civil War and with the advent of spirit photography, the movement grew, attracting Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Pierre Curie, William James, and Charles Dickens. As the authors note, the continued spread of spiritualism in the early twentieth century can, no doubt, be linked to the devastating losses suffered during World War I and the influenza epidemic.

An intrigued skeptic, the Scottish-born Doyle first took an interest in spiritualism in the 1880s, but for the next two decades he remained unimpressed by “table tipping” and other questionable antics until one of his wife’s spiritualist friends spoke to him about a “private, long-ago conversation” Doyle had had with his late brother-in-law, in which she revealed details Doyle was certain no one else could’ve known. In 1918, his son Kingsley died during the Spanish flu. One year later at a sitting, Doyle was visited by his son’s spirit, who asked his father’s forgiveness and said he was now happy. Over the next decade, Doyle became a prominent evangelist for the movement.

Bechtel and Stains have amassed news accounts, transcripts, and correspondence—a daunting feat, since Doyle never seemed to put his pen down. But at times the retelling of sittings and psychic debunkings grows baggy. The first account of mysterious knocks and bumps leaves a chill, though the moans and yodels start to blur, and the committee findings from a group of psychic researchers are still committee findings. The authors are clearly sympathetic to their subject, but in his gullibility and self-seriousness, Doyle ends up a somewhat simplistic figure, nowhere near as dynamic as the psychics with their ectoplasm secretions or Doyle’s friend Harry Houdini, who made a second career out of debunking mediums. The magician would attend sittings incognito “wearing a blond wig and glasses and calling himself ‘F. Raud’.”

Do we respond to the charlatan or fraud because they allow us to behave in ways that we otherwise deny ourselves? The authors are incisive about the ways that spiritualism created space for women to be seen and heard in the nineteenth century. As “trance mediums,” they could address assemblies, an unusual occurrence, and one that made for the movement’s intersection with women’s suffrage and abolition. A woman was readily allowed a voice if it appeared to belong not to her but to a dead person.

Certainly there was an erotic charge in those séances where men and women who were not married might touch hands in the dark. At one of the famous circles Doyle attended, the medium would wear nothing but a slip to ensure she wasn’t concealing any objects. During several sessions she sat barely clothed in a specially constructed box among a circle of men. Of course, as all of this was conducted in the name of scientific research, the necessary social norms remained intact.

In a 1985 interview, Elsie Wright admitted that she and her friend Frances Griffiths had composed the photos of the Cottingley Fairies for their own amusement, never imagining that public uproar would ensue, much less that a renowned author would turn their childhood lark into his own rallying cry. In the same interview, Frances marveled at the response: “I can’t understand to this day why they were taken in. They wanted to be taken in!”

Doyle and all the others were seeking more than the chance to sit in a circle holding hands. For a man committed to science, Doyle’s defense of spiritualism had a decidedly emotional foundation. He believed it offered solace, and that it was wrong of the detractors to deny that to anyone beset by grief.

What did the mediums report from the beyond the veil? The form and content varied, but the underlying messages were frequently consistent: I am safe. I miss you. I am happy. That would be consoling to hear. Also: You were loved. Any fraud could say it and it would still be the truth.

Liz Brown is currently at work on Twilight Man: The Strange Life and Times of Harrison Post, to be published by Viking. Her writing has appeared in Bookforum, frieze, London Review of Books, Los Angeles Times, New York Times Book Review, and elsewhere.