Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The Brooklyn Museum hosts a comprehensive—and long overdue—survey of the artist and her works of commemoration.

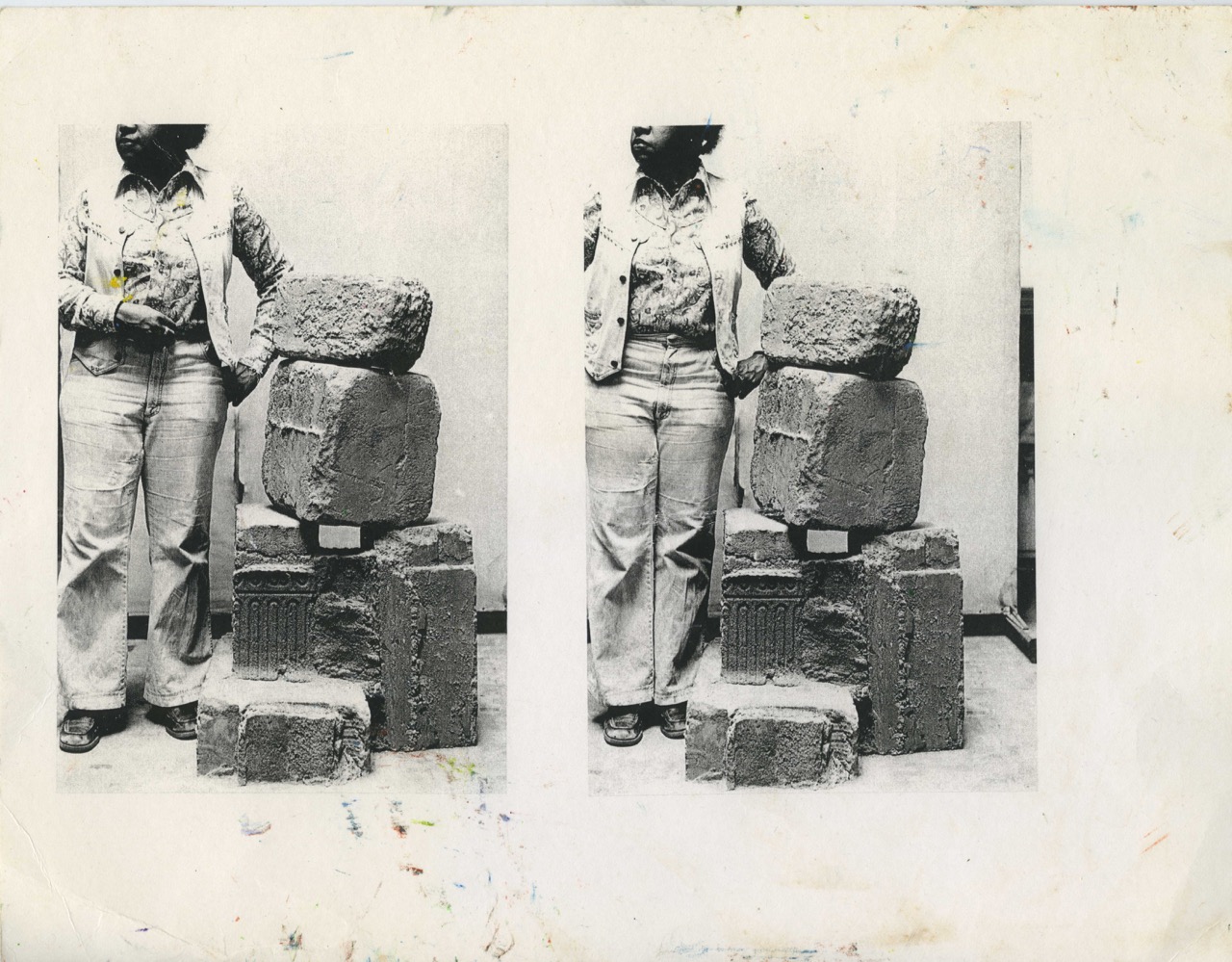

Beverly Buchanan, Untitled (Double Portrait of Artist with Frustula Sculpture), n.d. Black-and-white photograph with original paint marks, 8 1/2 × 11 inches. Image courtesy of Jane Bridges. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, the Brooklyn Museum, through March 5, 2017

• • •

If you want to find women artists and artists of color in museums, don’t look in the galleries—look in the archives. Sure enough, the spark for Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals, the first major museum survey of this criminally under-known artist, was curator Park McArthur’s chance discovery of a card for one of Buchanan’s New York gallery shows buried in a file in the Whitney Museum. At first with Buchanan’s participation, and then, after her death in 2015, with the help of a geographically dispersed network of family, friends, and supporters, McArthur and co-curator Jennifer Burris have reconstructed her career in the first exhibition of the Brooklyn Museum’s ongoing celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Elizabeth S. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. It traces Buchanan’s earliest forays into the professional art world in the late 1970s, when she was making everything from earthworks, conceptual photography, and sculpture to artist books, drawings, and found objects, to the later—and perhaps best-known—phase of her work, wooden “shacks” that were most often seen, when they were seen, as a form of folk or outsider art.

Never was there an outsider more on the inside than Beverly Buchanan: the relative obscurity of her work today—I’m ashamed to admit I’d never heard of her before this show—seems almost completely inexplicable in retrospect. She became a full-time artist relatively late in life, having first pursued graduate work in parasitology at Columbia and worked in public health in New Jersey. But when she did make the career change in her late thirties, it was with the support and mentorship of giants like Norman Lewis, with whom she had studied at the Art Students League, and Romare Bearden, whom she met, blinded by her admiration, by accidentally following him into a men’s room. One of her lifelong advocates was the pioneering curator of African-American art Lowery Stokes Sims; the legendary art dealer Betty Parsons was another supporter. In 1973, Lucy Lippard included her work in c. 7500, one of the most important and influential shows of women’s art of feminism’s second wave. She showed at A.I.R. gallery—another locus of advanced feminist art—in Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States, organized by Ana Mendieta in 1980. She received a Guggenheim award and an NEA fellowship in 1980 to support a site-specific project she planned in Georgia, when she moved back there to begin teaching at an art college. When she died, Alice Walker wrote a poem about her.

The trifecta of being a woman, being black, and—thanks to the New York art world’s myopia—of spending most of her career in the South, is, infuriatingly, explanation enough for her relative obscurity. The refusal of her practice to fit into any single category or genre may be another. But that eclecticism is superficial—never has a practice been so consistent in its devotion to questions of history: whose is recorded, and how.

The exhibition is divided into three parts, a logic determined by the architecture of the museum’s Sackler Center. In the first gallery, displayed on low risers or directly on the floor, are Buchanan’s frustulas, made mostly between 1978 and 1980. These small, blocky sculptures are made of a pigmented concrete admixture derived from soil found at the sites where she was working and cast using bricks and milk cartons. The laborious process resulted in what amount to crude artifacts—pre-ruined ruins—that were then grouped at resonant locations outdoors. (Dominating this room is a three-channel video made by the curators that documents an existing suite of these forays into land art.) The frustulas are an almost silent form of commemoration, a marking of events that don’t quite count as history, as when, for example, she deposited stones outside a business in New Jersey that had just ended its racist hiring practices. “I wanted something there to commemorate that without having a big giant sign that said ‘We finally hired some black people!’ So I took the stones I had in my car and made a little pile there. But I didn’t put a sign.”

Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals, installation view. Image courtesy the Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

The second gallery is filled with an eclectic mix of objects, most excavated from the artist’s personal archive amassed over a thirty-year period from the mid-1970s until her death, including: a small, bauble-encrusted “forget-me-not” of Lowery Stokes Sims; a report to the Guggenheim Fellowship Committee that documents—in hilariously mundane photos and text—the creation of Marsh Ruins, a public artwork in Brunswick, Georgia (“Wish I had a hat” is the deadpan caption to one picture); her photographs of the frustulas in her studio, rendered subtly animate by the sensitive play of light and shadow and the massing of their forms; hand-drawn and photocopied business cards, including my favorite, which announces “Beverly Buchanan: Renaissance Woman” and lists her services on offer (“Drawing • Magazine Modeling • Race Car Advocate • Painting • Yardwork • Sculpture”). Like so much on view here, these objects are infused with a humane and self-deprecating humor, an insistence on pulling the grandiose category of art into a humbler, but no less thoughtful or incisive, plane of existence.

Beverly Buchanan—Ruins and Rituals, installation view. Image courtesy the Brooklyn Museum. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

In the last gallery are displayed her shacks, small structures hammered together from reclaimed wood that follow the forms of vernacular architecture in the black South. Many are accompanied by “legends”: texts that tell the stories of their occupants, quasi-fictional accounts based on Buchanan’s extensive interviews with actual people who had built and lived in them. Despite the crudeness of the shacks—both the actual, unheated, unplumbed, and unwired houses and Buchanan’s recreations of them—they followed conventional designs with colorful names: shotgun houses, saddlebags, dogtrots, for example.

Like so much of Buchanan’s work, the shacks play with the idea of commemoration—their forms and groupings echo those of her frustulas—but, as always, she refuses commemoration’s gothic counterpart, namely nostalgia. Nostalgia, she said once, is for something lost. The shacks, on the contrary, are transformed, through her careful research, into a document of the hidden ingenuity of a community very much alive. This fact is underlined in a remarkable photograph of Mary Lou Furcron, a woman in her nineties who had built her rustic home without using nails (only mud, grass, and branches hold it together) entirely under her own steam, and who seems almost startlingly vital as she gazes out from its protection. Alice Walker, too, grew up in one of these rustic houses. In the poem she wrote in honor of her friend, Walker aptly describes the way that Buchanan made commemoration a forward-looking act: “How do we make new / And restorative of soul / The old pain?”

Aruna D’Souza writes about nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first-century art, as well as food, culture, diaspora, and feminism. Her essay “Dislocations: The Paintings of Toba Khedoori” will appear in Toba Khedoori (LACMA, 2016) this fall. She works at Bennington College.