Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Into the mind’s eye: the Guggenheim revisits the fin de siècle Rose+Croix Salons.

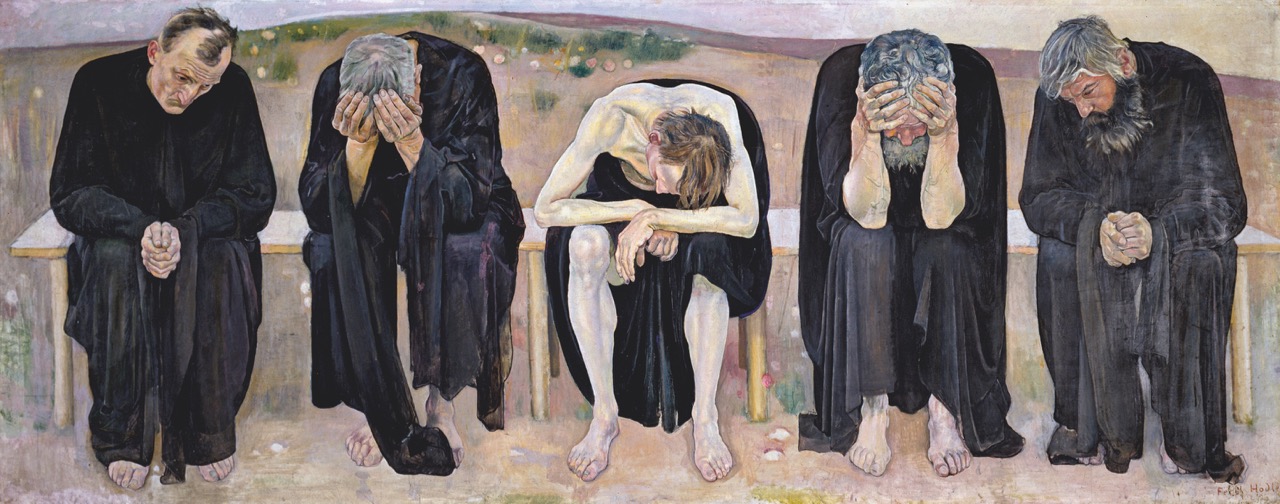

Ferdinand Hodler, The Disappointed Souls, 1892. Oil on canvas, 47 × 117.7 inches. Photo: Kuntsmuseum Bern, Staat Bern.

Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897, the Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through October 4, 2017

• • •

Like many other symbolist movements that popped up across Europe in the 1890s, the Paris-based Rose+Croix had no use for impressionism’s “painting of modern life,” which had dominated the French avant-garde in the 1870s and 1880s. Times had changed. The fin de siècle was a period of economic decline and deep cultural pessimism; the shiny newness of modernity that had enthralled a previous generation of artists was dulling, its cracks becoming apparent, its promise in doubt. Who wanted to make art of the real world when the real world was such a mess? Among other disasters, scandals, and turmoils, the decade witnessed the effects of a long-standing economic depression, the Dreyfus Affair with its anti-Semitic stench, widespread misogyny born of women’s increased participation in the public sphere, the rise of a virulent nationalism and the resurgence of deeply conservative social mores thanks to the influence of the Catholic Church, the misadventures of France’s imperial forces around the globe, disruptive labor strikes, and moments of (often violent) anarchist agitation.

So instead of painting railways and the city street and dance halls and brothels, the symbolists embraced the world of the spirit, of the dream, of the remote past and unrealized future, of gods and religion, of myth, of the eerie and strange. To this heady stew, Rose+Croix added ideas derived from the hermetic, occult practice of Rosicrucianism. The most devoted of the group’s members believed that they were the inheritors of an ancient wisdom that contained whiffs of Jewish mysticism, Christian Gnosticism, and a slew of other esoterica, and simultaneously embraced a deeply conservative Catholicism; they considered their charismatic and even cultish leader, Joséphin Péladan, a high priest, calling him “Sâr” (the Assyrian word for “king”) and depicting him in portraits as a holy man.

Armand Point, The Annunciation or Ancilla Domini (L’Annonciation), 1895. Tempera on panel, 39 × 20 inches. Photo: Sotheby’s.

At first glance, then, the Rose+Croix Salons—the six annual exhibitions held between 1892 and 1897 that were the primary manifestations of this short-lived group—would seem easy to write off as unrelentingly rearguard. But as Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897 at the Guggenheim makes clear, these artists’ turn to the world of the mind’s eye could accommodate a vast range of political positions: for some, it permitted a reactionary retreat from ugly political realities (or, worse, a doubling down on those realities), while for others it was a way of imagining new utopias. Sometimes, bizarrely, it was both. It could be expressed in the most traditional artistic languages or in the most avant-garde ones. Rose+Croix was a tent large enough to fit Armand Point’s The Annunciation of 1895—a throwback to the Catholic ideal of untouched womanhood and the mysteries of faith rendered in the style of the early Italian primitives—alongside equally thematically conservative, but stylistically much more radical, images of young female saints like Henri Martin’s 1891 painting of a virginal, haloed woman standing in a field of grain, rendered in the techno-rationalist, pointillist technique of the neo-impressionists.

Henri Martin, Young Saint, 1891. Oil on canvas, 25.7 × 19.4 inches. Photo: © Musée des Beaux-Arts, Brest, France.

The deep-red walls, plush blue couches, and piped-in music in the Guggenheim installation are meant to give a sense of the hothouse atmosphere and straight-up weirdness of the Rose+Croix salons, but frankly it’s not needed: the art is plenty weird enough. The woman who stares out of Fernand Khnopff’s I Lock My Door upon Myself (1891) has empty, deadened eyes, like a zombified Pre-Raphaelite heroine; the five life-sized figures in Ferdinand Hodler’s The Disappointed Souls (1892) sit, heads lowered in despair, all in a row, seeming almost like musical notes arranged on a staff. In both of these paintings, we seem to be encountering a poem half written, a strange truncated narrative in which the specter of death plays a leading role. Gender was clearly a source of great anxiety among this all-male brotherhood, judging by the forty-odd works on view, all of which were featured in one of the Rose+Croix Salons: the androgynous Orpheus appears in the exhibition so often that he could well be the group’s mascot, the femme fragile or woman-as-virginal-victim is a recurring theme, and the femme fatale plays a leading role.

Fernand Khnopff, I Lock My Door upon Myself, 1891. Oil on canvas, 28.6 × 55.5 inches. Photo: bkp Bildagentur, Berlin/Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich/Art Resource, NY.

In addition to a core of devotees, Péladan invited artists from all over Europe to participate in the Rose+Croix Salons whether or not they were true believers, and his taste was not terrible. He asked Puvis de Chavannes and Gustave Moreau, possibly the most famous and revered painters of the moment, to take part; both refused, but sent their students instead. Péladan invited Félix Vallotton, too—a curious choice, since Vallotton, part of the Nabi circle, was an overt anarchist sympathizer. (Like the staunchly Protestant Hodler, he was happy to oblige for purely self-promotional reasons—another chance to display work in a high-profile show in Paris.) It makes a certain amount of sense that Péladan would have thought Vallotton’s Japanese woodcut–inspired landscape prints, such as The Fine Evening (1892), meditative enough, and his portraits of intellectual giants like Richard Wagner (a favorite of the Rose+Croix) sufficiently reverential, to hang in his Salons. But it is puzzling to note Péladan’s willingness to include, in the very first of his shows, Vallotton’s The Paris Crowd (1892), which depicts a policeman attempting to rein in the possibly disruptive, possibly innocent masses on the city streets; it’s a work that nods precisely to the messiness of the world that the Rose+Croix was determined to supersede.

Félix Vallotton, The Fine Evening, 1892. Woodcut, 9 × 12 inches. Photo: MAH-CdAG © Collection des Musées d’art et d’histoire de la Ville de Genève, Cabinet d’arts graphiques.

A pair of paintings by Charles Maurin—The Dawn of the Dream and The Dawn of Labor, both shown in the First Salon de la Rose+Croix in 1892—are enthralling for the way they embody the contradictions of the group, and of the artistic moment. The Dawn of the Dream is pure symbolist sexual angst: a scene of nude women—innocents and femmes fatales, young and old by turn—gathered around a depressive poet on a park bench. In the triteness of its imagining, it is pure kitsch—the Penthouse letters section (or maybe a Reddit forum) come to life. And yet, in aesthetic terms it would not look out of place next to some of the most advanced painting of the decade: the flattened, abstracted, and heavily outlined bodies that jumble in the foreground and are cut off by the painting’s edges recall moments from Paul Gauguin’s visionary Breton paintings (think Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1888), Pierre Bonnard’s japoniste Nabi compositions, and so on. The Dawn of Labor is its stylistic twin but its conceptual foil, replacing emo-erotic fantasy with something quite different. Again, we have naked, writhing bodies in an urban space. But these women, children, and men are not caught in a poet’s dreamworld; they are struggling to follow a Liberty-Leading-the-People–type woman in a ruined, postindustrial landscape. For all their allegorical import and anti-realist stylization, they represent something very timely and real—miners and their families, fomenting revolution to claim the rewards that modernity has promised them. In an exhibition filled with artworks by men desperate to escape the changes happening in the world around them by retreating into fantasies in which the authorities of old (church, patriarchy, gods, kings) once again had full sway, the Maurin painting reminds us that then, as now, the true escape is revolution.

Charles Maurin, The Dawn of Labor, ca. 1891. Oil on canvas, 31 × 58 inches. Photo: Yves Bresson, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, Saint Étienne Métropole, France.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and The Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson, and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.