Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A pedagogical art project pursues environmental justice through drawing.

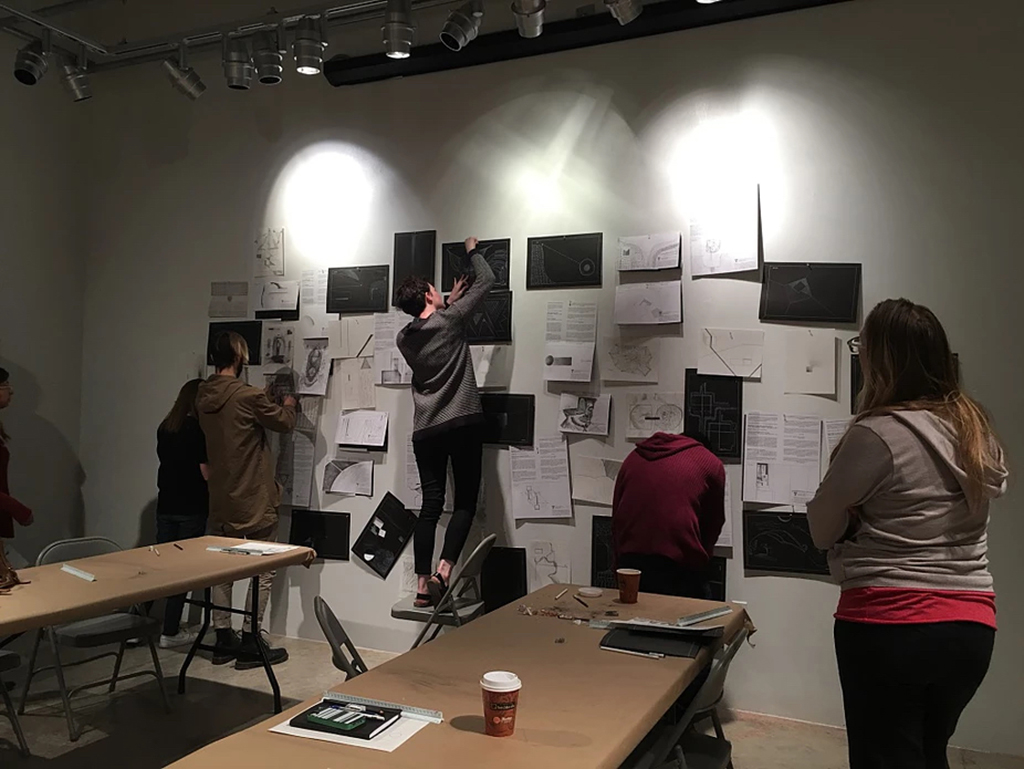

Winter Term: Torkwase Dyson and the Wynter-Wells School for Environmental Justice, installation view. Image courtesy The Drawing Center. Photo: Martin Parsekian.

Winter Term: Torkwase Dyson and the Wynter-Wells School for Environmental Justice, the Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, New York City, through March 11, 2018

• • •

In recent years, and especially after the November 2016 election, the question of how museums should define their political role has become more urgent. While, with few exceptions, US art institutions have long imagined themselves as neutral and objective platforms for cultural display and debate, artists, art audiences, and even their own staff are increasingly hungry for a more activist approach. Recent attempts to confront the zeitgeist have included the Museum of Modern Art’s decision last February to take out of deep storage works by artists from countries affected by Trump’s Muslim ban; the Whitney Museum of Art’s J-20 “speak out” last year, in which artists, organizers, and writers (myself included) laid out a vision for resistance to the new political order and a call to transform cultural institutions on the occasion of Trump’s inauguration; and exhibitions at institutions around the country dealing with protest, immigration, #metoo, and so on.

The Drawing Center jumps into this fray with Winter Term. The new annual initiative consists of public events, classes, performances, and an exhibition, each with a different artist or organization at its heart. Its goals are both lofty and granular, combining a desire to grapple with some of the biggest issues that affect our world with a tight, mission-driven focus on drawing itself. This limited purview offers unique prospects, as the first iteration of the program—Torkwase Dyson’s Wynter-Wells Drawing School for Environmental Justice—makes clear.

Wynter-Wells Drawing School for Environmental Justice workshop at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, 2017. Image courtesy the Drawing Center.

It is hard to imagine a better inaugural artist for Winter Term than Dyson, whose work revolves around the idea that drawing is a means through which ordinary people can enter into conversations they might otherwise feel powerless to join. Dyson’s nomadic “pop-up” art school has been offering classes (free, but by application only; the public can observe in the afternoons); conversations with architects, designers, and historians; office hours, during which Dyson works at a large table in the center of the gallery, answering visitors’ questions; a “movement score” inspired by the ongoing work of the school, choreographed by Andres Luis Hernandez and performed by Zachary Fabri; and an installation of Dyson’s drawings, prints, and sculptural works. Among other things, Wynter-Wells is an experiment in radical pedagogy, in which Dyson is not a teacher in any authoritative sense, but a facilitator, and in some ways a student. (She described the project to me as a chance for her to think across disciplinary boundaries, both thanks to the diversity of those taking classes as well as the range of artists, performers, and thinkers participating in the programs.)

While the artist’s own work encompasses painting and sculpture, Dyson has long treated drawing as a foundational medium. For her, it functions as a sort of micro-action, suitable for understanding problems that are so massive, systemic, intractable, and global as to exceed our conception—what the philosopher Timothy Morton, a figure who plays a central role in her thinking, calls “hyperobjects.” Our current environmental crisis is foremost among these, as is anti-blackness—the two intertwined issues to which the Wynter-Wells project is addressed. The institute is named in honor of Sylvia Wynter, the Jamaican writer, and Ida B. Wells, the nineteenth-century journalist, two figures central to Dyson’s elaboration of her idea of “black compositional thought.” The term, devised by the artist, refers to the ways our everyday landscapes have been molded by black bodies trying to survive or escape oppression (as when a path is cut through a forest by people fleeing enslavement) and, conversely, the ways in which place, space, and location define who is understood as fully human, and who is not.

Students in the first class were each given a large, intricately folded poster and asked to draw on it. Printed on the poster was a series of framing questions and quotations: “What is the relationship between labor, mass incarceration, and global warming?” “How are existing forms of abstract drawing tied to notions of natural resources, self-emancipation, and geography? Saturated grounds, continued extraction, changing shorelines, and infrastructural developments are modifying the earth’s atmosphere. Can something new be done with minimal, geometric forms to communicate this spatial phenomenon subjectively . . . Poetically . . . ?” They were offered prompts for these five-minute drafting exercises, including terms such as “movement, edge, body, state change, how blood flows, how water flows, how soil flows”—breaking down large concepts into visceral and visual terms. The goal seems less about teaching us how to draw and more about showing us that we can draw—that it is an innate skill that we all possess. This is what makes Dyson’s project so interesting, to my mind: by offering ideas on how to use that skill to address otherwise insurmountable problems, even in a small way, she allows us to enter the fray as active participants rather than remaining powerless bystanders. If Wynter-Wells functions to reorient the museum in a more activist direction, it does so by turning us, its audience, not simply into draftspeople but into political actors.

Torkwase Dyson, Black (Hyper Shape), 2017. Acrylic, graphite, wire on panel board, 48 × 48 × 13 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

But this is, at heart, an art school, even if an unusual one, and as such there is not only a desire to bring the knowledge that drawing can produce into climate change debates but also an insistence on translating the vast and tentacular challenges of climate change into drawing’s own terms. In her own work, Dyson achieves this by recourse to “hypershapes”—basic shapes that are so prevalent in the visual landscape as to be almost inescapable, the artist’s formal correlates of Morton’s “hyperobject.” The curve that shows up repeatedly in the work that lines the walls of the Drawing Center for the duration of Wynter-Wells—in her gouache and pen drawings (Untitled [Hypershape]), her wood, graphite and marker assemblages (Untitled [Hypershape Woodwork #22]), and her painterly, graphite-covered panels (Water Table)—might suggest an elevation diagram of a reservoir or lake, the belly of a slaver’s ship, the hold of a cargo vessel, or even the line of a shoulder, linking environment, bodies, commodities, and race in glancing and suggestive ways.

Torkwase Dyson, Black Interiority, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 72 × 120 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

The interdisciplinarity that Dyson seeks in Wynter-Wells’s pedagogy is reflected in her own work, which evokes abstract expressionism, minimalism, Russian avant-gardism, and other forms of modernist abstraction, along with architectural notation, Asian ink drawing, geographical renderings, mathematical diagramming, and even (in her use of thickly layered liquid graphite and handmade paper collage elements in a piece like Scalar #2, De-Territorializing [Water Table]), geological sampling. Into the Wake—a suite of large drawings that takes its title from an influential book on race by one of Dyson’s Wynter-Wells interlocutors, Christina Sharpe—breaks down the hypershape curve into a series of fluid, transparent brushstrokes that overlap; the effect is both three-dimensional and schematic, as if one is looking at a computer rendering of objects in space and a simple map at once. At the same time, those arcing strokes vividly recall the hand, and body, that made them—they are keyed to her reach and her movement. Such assured and frankly beautiful works demonstrate that whatever the political efficacy of the project—at the time of this writing, in the early days of Winter Term, that remains to be seen—the aesthetic results are certainly worth the effort.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, will be published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.