Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Record achievement: a holy grail of sound art gets recreated.

Broken Music, edited by Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier, Primary Information, 278 pages, $34

• • •

It’s almost hard to recall the days before the internet achieved total dominance, when elaborate paper compendiums like Broken Music functioned as secret keys to hidden universes. Like the zine directory Factsheet Five, or the recently departed Village Voice, print publications compiled what was cool, what to read, what to hear, and what to see; they were gateways to tantalizing realms one hadn’t yet experienced.

The book Broken Music, published in 1989, is one of the holy grails of sound art. Original copies of the sumptuous, nearly 280-page tome now fetch several hundred dollars. Edited by Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier, it was initially created as a catalog to accompany an exhibition they both organized at daadgalerie in Berlin. Think of Broken Music as a kaleidoscopic atlas to experimental sound and artists’ records, long before the advent of the World Wide Web. I encountered a first edition of Broken Music some years ago in the collection of a friend, wishing madly that I had my own copy as I gingerly turned the fragile pages.

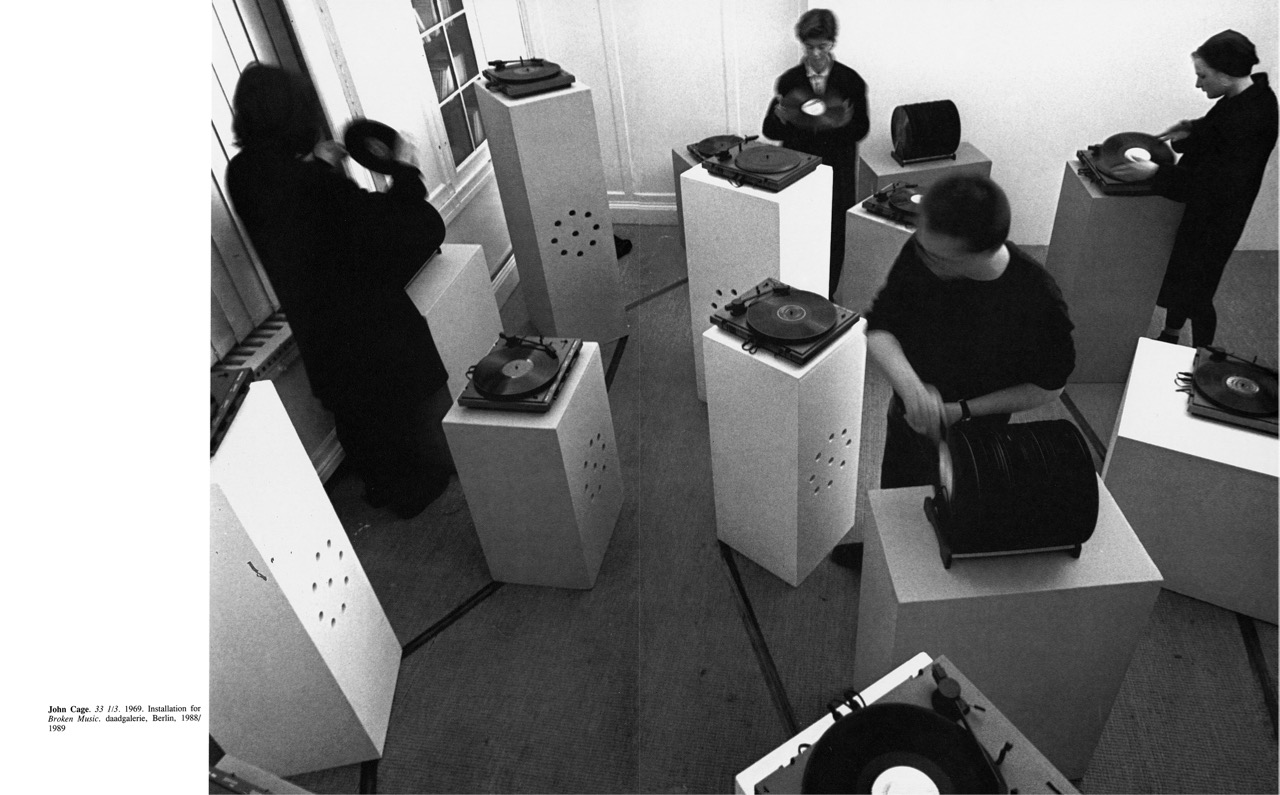

John Cage, 33 1/3, 1969. Installation for the Broken Music exhibition at daadgalerie, Berlin, 1988/1989. Image from the pages of Broken Music, courtesy Primary Information.

The estimable Brooklyn publisher Primary Information recently issued a meticulous recreation of the rare book. All of the original details have been faithfully replicated, right down to the attached vinyl flexidisc of one of Czech artist-musician Milan Knížák’s startling sound collages, performed by the Arditti String Quartet. The first half of the book includes reprinted essays by luminaries such as Theodor Adorno, László Moholy-Nagy, and Jean Dubuffet, and the text is simultaneously presented in German, French, and English translations. The second half is a lengthy annotated index of hundreds of records and works by artists and musicians. Some, but not all, of these entries are adorned with helpful explanatory text and numerous lush images (including John Cage’s geometric graphic score for Imaginary Landscape No. 5; Joseph Beuys’s eerie sculptures of gramophones festooned with bones and blood sausage; and an expansive floor installation by Christian Marclay, One Thousand Records, at gelbe Musik in 1988.)

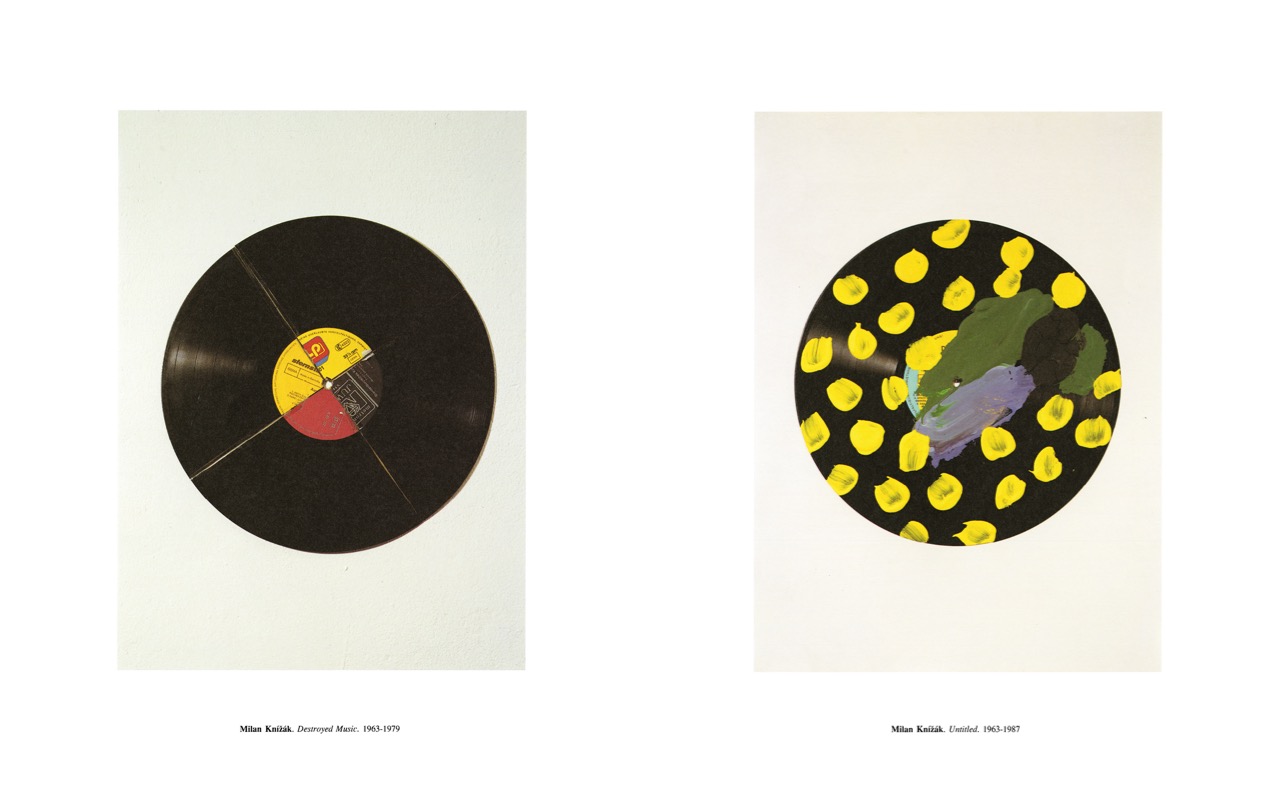

The book takes its name—and inspiration—from a series of chaotic, transformational works by Knížák. “In 1965 I started to destroy records: scratch them, punch holes in them, break them,” he writes in the book. “By playing them over and over again (which destroyed the needle and often the record player too) an entirely new music was created—unexpected, nerve-racking and aggressive. Compositions lasting one second or almost infinitely long (as when the needle got stuck in a deep groove and played the same phrase over and over again). I developed the system further. I began sticking tapes on top of records, painting over them, burning them, cutting them up and gluing parts of different records back together, etc to achieve the widest possible variety of sounds.”

Milan Knížák, Destroyed Music, 1963–79, and Untitled, 1963–87. Image from the pages of Broken Music, courtesy Primary Information.

Knížák’s pieces are some of the most dynamic and exciting documented in the book, which largely details works made with records, not tape. As Block writes in her opening essay, “Broken Music shows works of visual artists created with and for the medium of the record: records, record-covers, record-objects, record-installations. In contrast to the composer or musician who perceives the record first and foremost as a vehicle transporting his musical ideas, the visual artist is especially interested in the optical as well as the acoustical presence . . . Broken Music stands for a break with conventional ideas, as a breakthrough into something new.”

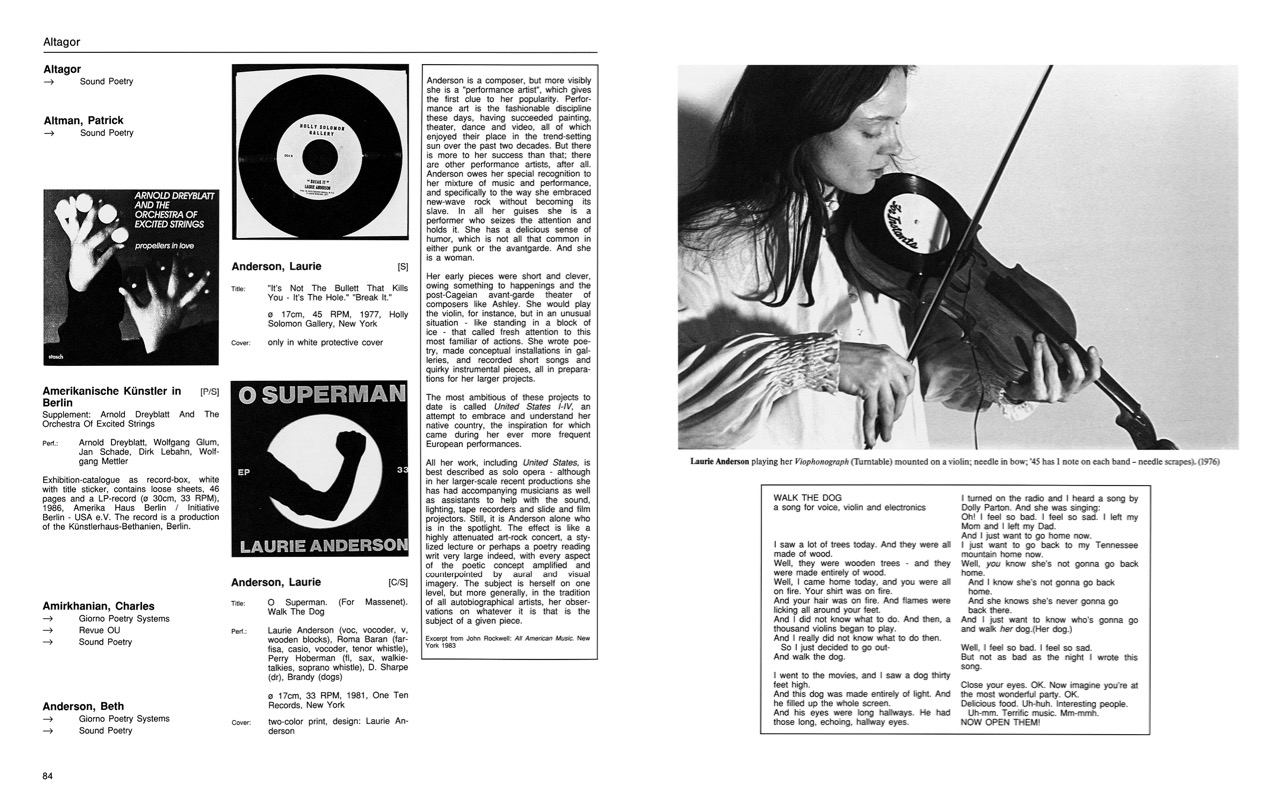

Laurie Anderson featured in the pages of Broken Music. Image courtesy Primary Information.

Looking back now, nearly thirty years after the exhibition and book were first created, it’s easier to see some of the holes in the history Broken Music is presenting. There are numerous works by well-known male artists (Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, Buckminster Fuller, Hans Haacke, Martin Kippenberger, Kurt Schwitters, and Richard Serra, among others), but relatively few women (Yoko Ono, Annea Lockwood, and Meredith Monk are listed, for example, but the information provided about them is slim). This is curious, because the book opens with a striking image of a woman: the musician Hermine in a chic strapless gown, putting vinyl records into a dishwasher. (The off-kilter domestic scene was the cover for her 1982 album The World on My Plates.)

Record art by Robert Rauschenberg. Image from the pages of Broken Music, courtesy Primary Information.

Also, while cover art by several prominent visual artists—including Andy Warhol, Richard Hamilton, Gerhard Richter, and Robert Rauschenberg—is documented, the records depicted are mostly centered around rock music, overlooking the iconic covers created for jazz albums by noteworthy artists. Warhol didn’t just do art for rock bands like the Rolling Stones and the Velvet Underground; he also created memorable covers for Thelonious Monk, Count Basie, and many others.

There are also few works by people of color. Hip-hop was at one of its creative peaks in the late 1980s when the book was published—an entire genre that was built on hacking, modifying, and sampling records—but hip-hop, along with DJ culture, disco, and other forms of dance music, is largely absent from Broken Music’s story.

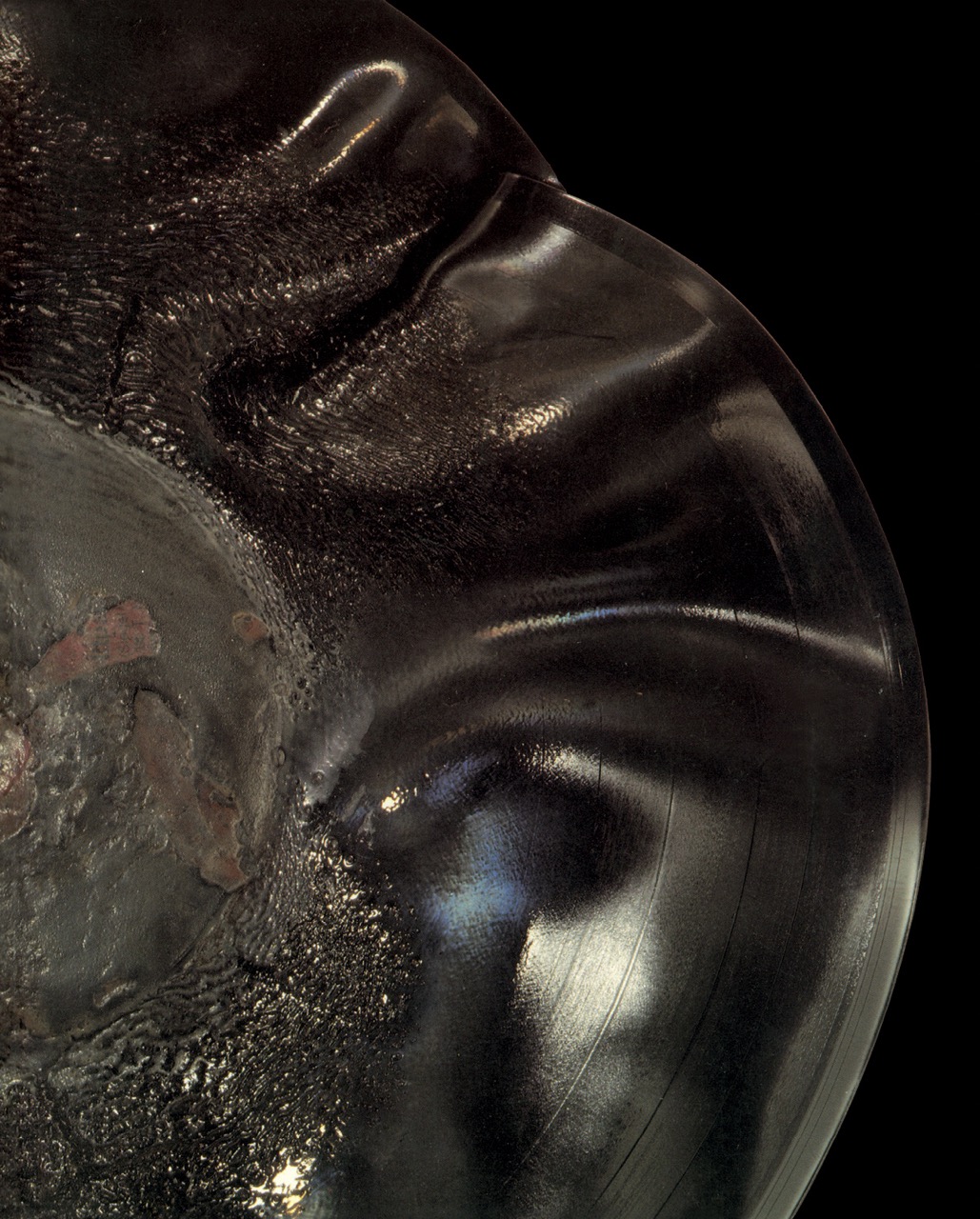

Image from the pages of Broken Music, courtesy Primary Information.

The book and exhibition were created in Europe, and its Eurocentric approach is perhaps understandable. In developing countries at that time, turntables were far less common, and presumably art created using the medium of LPs was less common too. In India, for instance, vinyl records certainly existed, but cassette tapes were far more prevalent; they were cheaper, more portable, and easily dubbed. As vinyl records have come back into vogue, it’s worth remembering that vast swathes of the world’s population didn’t use records, or turntables.

Broken Music was a tremendous work of scholarship for its era, and Primary Information has done a wondrous job in resuscitating this important historical document, which is still one of the key relics of sound art and culture. The time has come for a revised and updated version—one that plugs the gaps in its fascinating history.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.