Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Remembering the legendary jazz pianist.

Cecil Taylor performing at Keystone Korner, San Francisco, California, 1977. Photo: © Kathy Sloane.

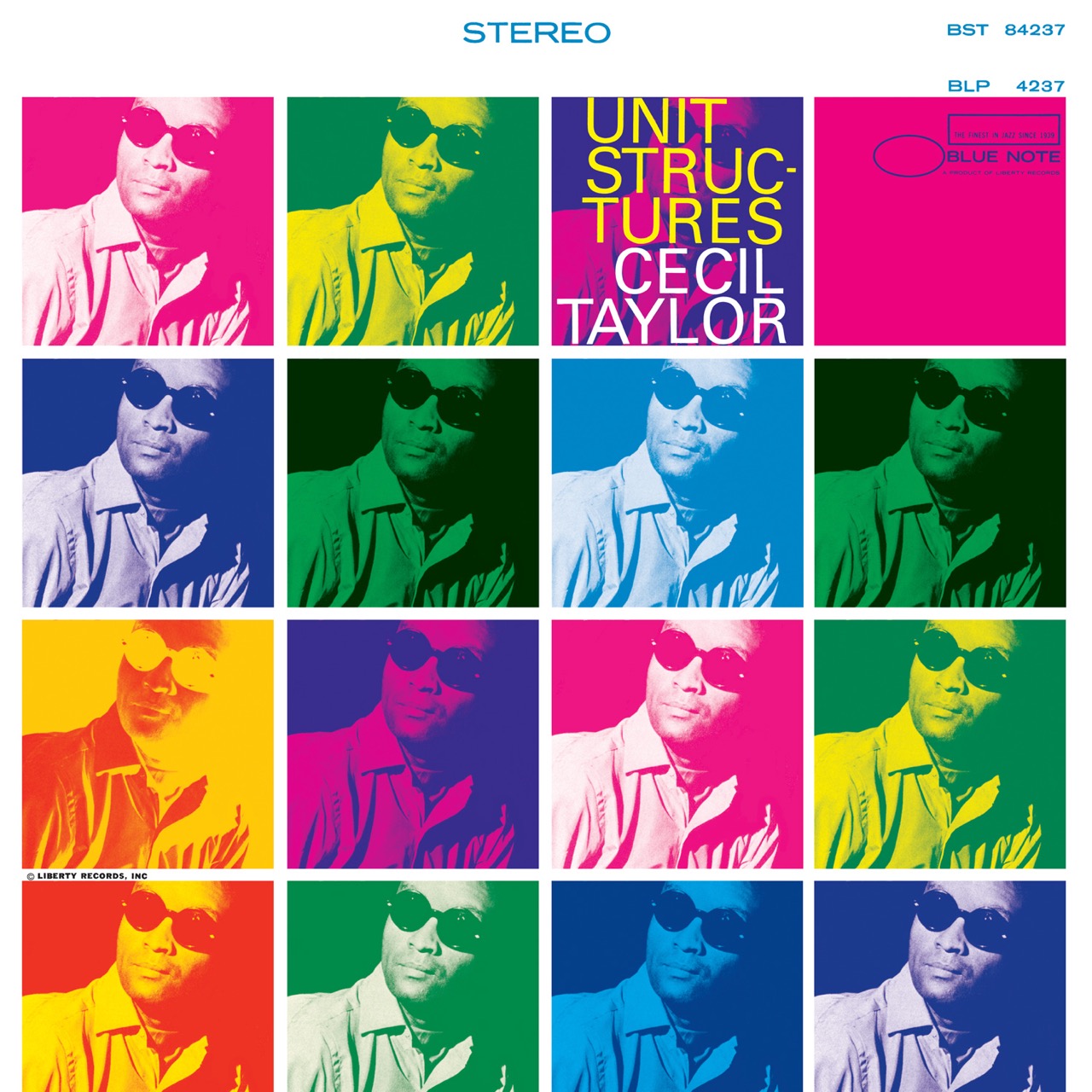

The jazz legend Cecil Taylor passed away earlier this month, at the age of eighty-nine, and his monumental body of work—encompassing seven decades—will take a very long time to fully decode. His densely packed liner notes for the album Unit Structures, from 1966, dropped early clues to his wide-ranging field of vision, referencing, among other things, Billie Holiday, Africa (Sudan, the Maasai, the Zulu, the Yoruba language, the river Nile), slavery, rhythm, the physics of acoustics, the jazz pianist Bud Powell, and the Bolshoi ballerina Maya Plisetskaya.

“Creative energy force = swing motor reaction exchange/fused pulse expands measured activity relating series of events,” Taylor wrote in the liner notes, in one particularly mind-bending equation. “Explosive dynamics filter graduated tempi/a molecular condition of bearing/special levels qualitatively diverse and special/emerging event holds traditional recording men’s actions in heat life variable knit accord history silent a language in balance, direction. Rhythm then is existence and existence time, content offers time quantity to shape: color, mental physical participation.”

Taylor’s piano playing was highly precise and technical; every improvised note felt deliberate, each cluster of notes delicately organized. But this was also very immediate music; it was intensely cerebral, but it worked on an emotional level, too. “I am not interested in compositions, in discipline, and all that academic stuff, where everything is determined,” said Taylor in an interview in Cadence magazine in 1984. “That’s all prison cells.”

When I encountered Taylor’s music for the first time, I felt an instant jolt, a sort of epiphany that this kind of music was even possible. I studied classical piano for several years in a conservatory when I was younger, and a lot of my training there was “all prison cells,” about what you weren’t allowed to do. There were a lot of rules, and each regimented lesson was like a disciplinary action. In Beethoven sonatas I achieved some catharsis, hammering down on those notes like drums, the left hand all percussion.

Taylor’s stormily percussive style felt recognizable to a conservatory piano student, but this wasn’t classical music, or “modern classical music,” but a unique breed of jazz. Though several critics have pointed to Taylor’s academic training at the New England Conservatory and the (now-defunct) New York College of Music—drawing connections between his work and the piano compositions of twentieth-century composers like Pierre Boulez and Olivier Messiaen—Taylor named jazz greats as his prime inspirations, especially Duke Ellington. “The most obvious influence on me has always been Duke Ellington as a pianist, as a composer, in many different ways,” said Taylor in Jazz Journal in 1980. “It was from Ellington that I derived an orchestral approach to the piano.”

The lineage from the misty elegance of Ellington to Taylor wasn’t always obvious. Taylor’s music was bracing, like taking an ice-cold shower. Each phrase was jammed with such a velocity of ideas that you got a sort of head rush. A fierce, sharp attack would be followed by a furious tumble of notes, a volley of unlikely chords hitting like a series of electric shocks.

Cecil Taylor. Photo: Francis Wolff.

The piano, as Taylor told The Wire in 1987, “is primarily a percussion instrument.” When asked why he didn’t generally use the sustain pedal, a common tool to soften and elongate the notes, Taylor offered a typically tough-minded answer. “Because first of all I want clarity of sound, I want the precision of the note as it is struck,” he argued. “Also, it’s easier to play with pedals, I’ve watched pianists play with pedals and you can’t hear what they are doing, what you hear is a blur . . . Playing Bach, for instance, when I was eight or nine, it became very clear that each note was a continent, a world in itself, and it deserved to be treated as that.”

Taylor was a master at his craft; he was hyper-disciplined, and free at the same time. In some ways, the jazz world wasn’t ready for him. The late bassist Buell Neidlinger, who played with Taylor for many years, spoke memorably of the hardships they experienced in the early days at jazz clubs, with Taylor often wrestling with ramshackle, out-of-tune pianos and being told to stop his challenging, lengthy sets partway through. “We’d be playing along for an hour or so and I’d get the old radio signal—the hand across the throat,” Neidlinger recalled to A.B. Spellman in the book Four Lives in the Bebop Business. “Cut ’em off! Cut ’em off!”

“But you can’t,” Neidlinger continued. “If Igor Stravinsky was sitting down writing, you wouldn’t all of a sudden run in and say, ‘Stop it, Igor! Like, we want to sell a few drinks!’ It’s about the same thing. You can’t tell Cecil to stop.”

Cecil Taylor, performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art, April 14, 2016, as part of Open Plan: Cecil Taylor. Photo: © Paula Court.

Taylor’s performances often incorporated more than music. Poetry and dance weren’t mere add-ons, but essential parts of the Cecil Taylor experience. “It’s more than physical,” he once explained to the critic Howard Mandel in the Washington Post. “My playing is like using all the aspects of one’s mind . . . So I dance, I sing, I write poems, I have these books here, because it means something. That’s what I’m putting into this music; this is also what I bring to people I’m close to. This is the simplest version of a spiritual transformation which has to do with the state of trance.”

Taylor was also an extraordinary teacher. When I interviewed the Pyramids—a group that studied under Taylor during his legendary run at Antioch College in Ohio in the early 1970s—the tales of Cecil the professor were legion. Taylor brought in instructors to teach theater, dance, and poetry in addition to music, set up a rambling student music group called the Black Music Ensemble that held regular late-night jam sessions, and delivered poetic lectures about African civilizations. The album Indent—a live recording made at Antioch College in 1973, later released on Arista/Freedom in 1977—prominently sported his long, fiery poems on the back cover of the LP.

Contending with Cecil Taylor means contending with more than music. His place as a towering figure in jazz is secure, but he should also be grappled with as a teacher, a poet, a performer, an artist, a profound thinker on race and black America. His legacy belongs not only to jazz, but to all of the arts, and the full range of human experience.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.