Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

From Brooklyn to Nuremberg: Open City novelist Teju Cole offers a book of photographs and short prose.

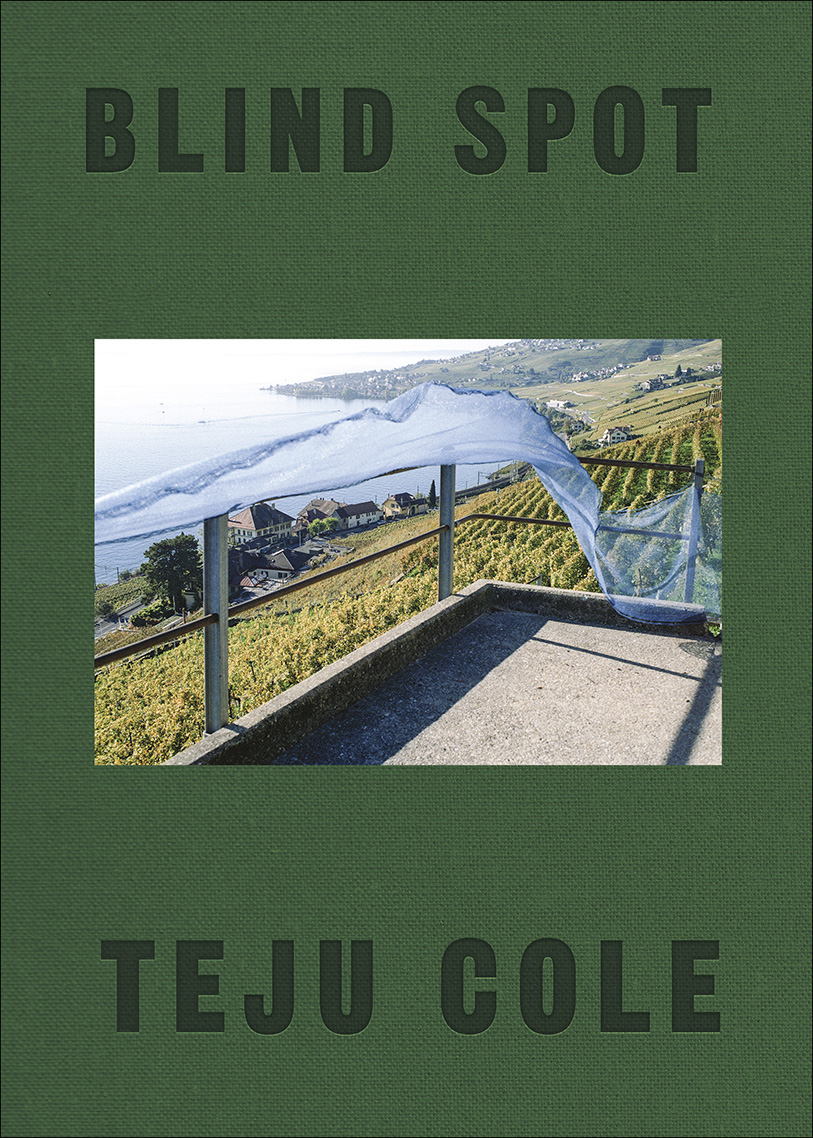

Blind Spot, by Teju Cole, Random House, 332 pages, $40

• • •

Teju Cole, the Nigerian-American writer best known for his 2011 novel Open City, is remarkable among his contemporaries for having maintained for years a genuine commitment to both literature and photography. It is easy to think of writers in whose books pictures play a significant narrative and textural role—consider W.G. Sebald, about whom Cole has written more than one essay—or for whom photography seems a respite from the rigors of the page. (Admirers of Janet Malcom’s briery prose may be justifiably dismayed by her genteel studies of burdock leaves.) But Cole is the real ambidextrous deal, and this new book of photographs and prose fragments confirms that he’s an accomplished practitioner in both fields—also, an artful thinker about how they fit together and come apart. A travelogue of sorts, Blind Spot takes him from Brooklyn to Lagos, Berlin to São Paulo, and on the way ventures oblique comments on such subjects as ISIS and Syria and racist violence in the United States.

For the most part, prose and picture are cleanly and classically arrayed: words on the left-hand page and image on the right. Cole begins in a register that seems both acute and melancholy, more than a little reminiscent of the Roland Barthes of Empire of Signs—Barthes alert but adrift in unfamiliar Tokyo. The first photograph in Blind Spot shows a clapboard house in the sunshine, partially hidden by a hedge with a haze of green buds. The accompanying text starts thus: “Spring, even in America, is Japanese. It is not only the leaves that grow. Shadows grow also.” Where do they grow, exactly? The piece is titled “Tivoli,” but this is for sure not central Italy. There’s a big RV behind that hedge too. Tivoli, New York, then? Tivoli, Texas? Cole’s short text expands to speak of spring as “the most melancholy season,” then rehearses an anecdote from Chris Marker’s 1983 film Sans Soleil: a Japanese man who killed himself in the unbearable first spring after his lover’s death.

Much of Blind Spot proceeds in this fashion, Cole’s lapidary captions touching their attendant images in places, but wandering away from them to point at a constellation of artists, writers, and philosophers. In a hotel room in Nuremberg, he photographs the curtained window, and knows we may think of the frontispiece Polaroid in Barthes’s Camera Lucida, or even of Nicéphore Niépce’s view of a rooftop and trees through his window, made in 1827: very likely the first-ever photograph. Albrecht Dürer’s house is around the corner from Cole’s hotel, and he recalls how Dürer learned to draw drapery by looking at Leonardo. So far so aesthetic, even precious. But we are in Nuremberg: darker histories (Hitler’s rallies, the postwar trials) are not far away. The European portions of Blind Spot are constantly discovering evidence of catastrophic violence. In calm and ordered Zürich, a window full of café chairs and street reflections abuts a wall bearing the graffiti of a stenciled cowboy drawing his pistol: a reminder for Cole that Switzerland sells arms to Saudi Arabia, Botswana, UAE. (The Swiss photographs might also evoke James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village,” on his experience of racism in Switzerland, and what it taught him about American racism.)

In spite of its author’s admiration for Sebald’s “poetry of the disregarded”—as Cole put it in a New Yorker piece in 2012—Blind Spot is emphatically not the sort of doleful prose meander, with snapshots, that one finds in vagrant works such as Sebald’s Austerlitz and The Rings of Saturn. Cole’s tiny essays are too tightly controlled for that, and function more like Renaissance emblems, placing title, text, and image together in arrangements that resemble riddles. It is our job to finish thoughts that only partly reveal themselves, to make for example a connection between Cole’s stated grief “because America kills black children” and the photograph of sunlit flowers in a Brooklyn window that accompanies it across the page. At times, however, the texts themselves can sound obvious in their deployment of certain talismanic names, as when Cole photographs a portion of a classroom map, and cites as reference points the poet Elizabeth Bishop, photographer Luigi Ghirri, and writer Italo Calvino.

Perhaps something similar occurs in Cole’s photographs, when one is faced with roughly one hundred and fifty of them: a too-present sense of his precursors pressing at the borders of images that are otherwise almost unpeopled. Here is a trio of white garden chairs on a threadbare lawn, bookended by bright green bags of trash, such as William Eggleston might have noticed but not composed quite like this. There is an office interior, or a stretch of anonymous concrete, that Lewis Baltz or another of the New Topographics photographers would have framed a little more starkly. Or a tessellation of confused reflections in store windows or café mirrors that Saul Leiter would have loved. There are much worse influences to which a contemporary photographer might admit; but there’s also a suspicion that Cole’s images—all these enigmatic edges and corners, these signs and murals, these objects of all sizes sheathed in plastic—remain politely in thrall to their antecedents.

These are smaller caveats than may seem. Blind Spot is after all a hybrid work, and as much about the relationship between prose and photography as anything else—a degree of self-conscious invoking of photographers and photography is entirely justified. The title of Cole’s book is a reference to a crisis that overcame him while he was composing it. One morning in the spring of 2011, he writes, he woke to find he was blind in one eye as a result of perforations to his retina. The dialectic of blindness and insight, the misjudging of distance that monocular vision will force on you, the amazing metaphorical potential of being treated for blindness by having lasers shot into your eye: all of this richly ghosts Blind Spot just as much as its literary and artistic influences. It’s a work at once of profundity and lightness—a world shuttered, wound on, begun again.

Brian Dillon’s books include Essayism (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017), The Great Explosion (Penguin, 2015), Objects in This Mirror: Essays (Sternberg Press, 2014), and The Hypochondriacs (Faber & Faber, 2009). He is UK editor of Cabinet magazine and teaches critical writing at the Royal College of Art, London. He is writing a book about sentences.