Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

From Hannah Arendt to Susan Sontag to Nora Ephron: a look at female essayists in the postwar literary world.

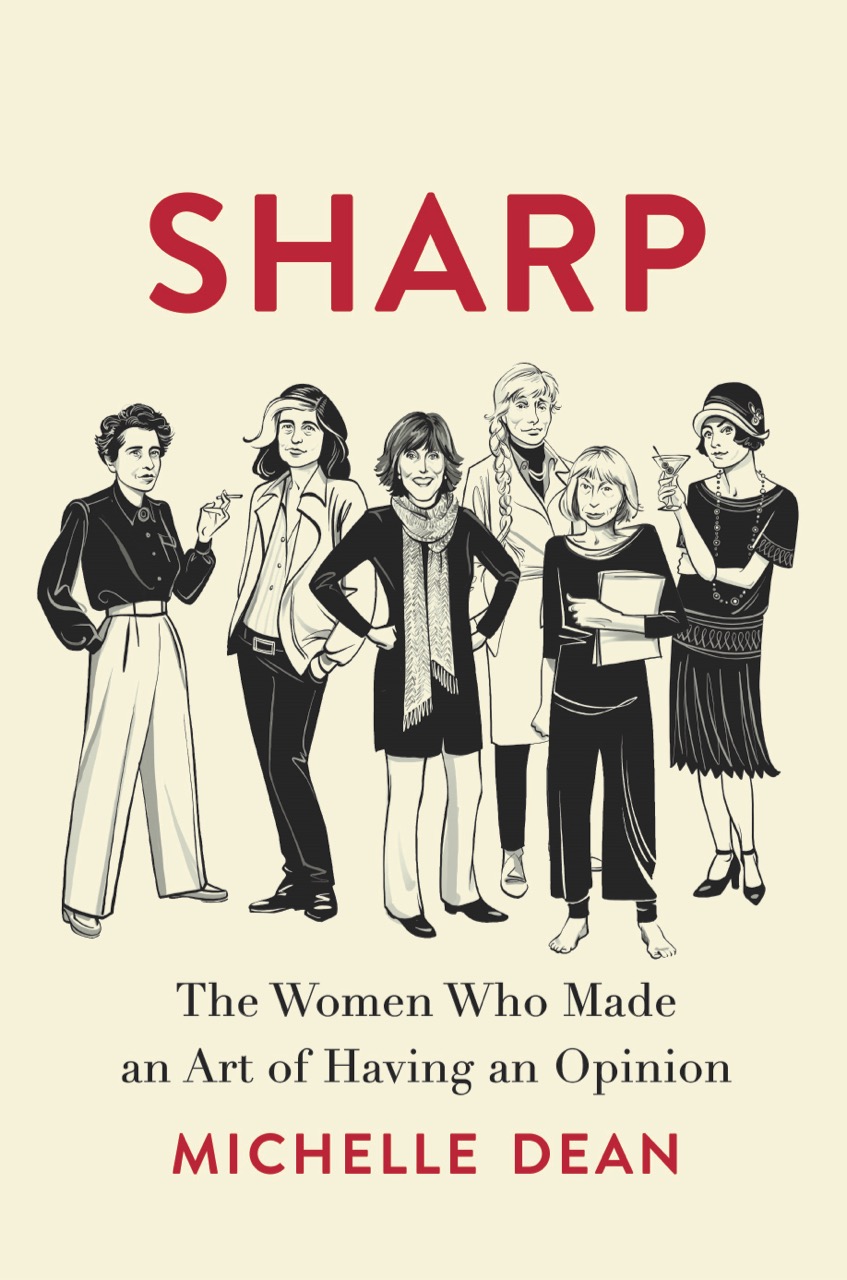

Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion, by Michelle Dean, Grove Press, 362 pages, $26

• • •

If you’re a smart, young, female, and (usually) white essayist in the US today, it’s likely somebody (reviewer, blurb writer, PR person) will sooner or later compare you favorably to Joan Didion. If your work has a more critical cast—though it will almost certainly lack her hauteur—the comparison may instead be with Susan Sontag. Flattering company for sure; but what a pitifully small range of literary forebears are allowed the contemporary female nonfictioneer. Who are the new Diana Trillings? Where the heirs to Elizabeth Hardwick? We might go looking for them in recent essay collections by the likes of Leslie Jamison, Eula Biss, and Durga Chew-Bose. But in their mainstream reception, print or online, female essayists and critics are still frequently denied much of a lineage outside of the sainted duo, Susan and Joan.

Michelle Dean’s Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion is partly an effort to constellate the stars whose influence bears on the present generation of essaying American women. Sontag and Didion are of course among the book’s twelve subjects, alongside writers who may seem worlds apart (Hannah Arendt and Pauline Kael, for example) but turn out to connect in life, in subject matter, or style. By “sharp” Dean intends a combination of wit, rigor, and principled truculence. The word itself was more often used about and even against these writers than as a means of self-definition—Dean means to rescue sharpness as literary value. After a spirited preface in which Dean pits this quality of certain women’s writing against the pantheon of American men, the book proper begins dutifully, and with a dismayingly unsharp sentence. “Before she was the lodestar she later became, Dorothy Parker had to go to work at nineteen.” One has the sense that the rather weak and distanced opening chapters—on Parker, Rebecca West, and (briefly) Zora Neale Hurston—have been loosely prefixed to a much tighter project, which is all about the ways women who were not quite, or not yet, feminists made their way in the postwar literary world.

To a large degree, they did it in the pages of magazines. This is true even of an academic eminence like Arendt, who after her exile to New York in 1941 began writing articles that were, says Dean, “halfway between academic treatises and modern newspaper editorials.” Thanks to the cultural as well as intellectual currency of the Partisan Review, Arendt became “an icon whose ideas were, for many of her admirers, secondary to the figure she cut in public life.” For her detractors, too: the poet Delmore Schwartz called her a “Weimar Republic flapper.” Such was the position most of Dean’s subjects occupied—matching style with seriousness in the pages of widely read periodicals—that their missteps and successes might be disparaged equally, in plain view. Vulnerability came with the task of keeping sharp.

Arendt is followed in Dean’s canon by Mary McCarthy; the pair were unlikely friends and allies in a scurrile, sometimes outright aggressive, literary milieu. Dean recounts how McCarthy’s bestseller The Group was parodied in the New York Review of Books by her supposed friend Hardwick. Here, as elsewhere in Sharp, Dean is unforgiving of those inclined to treat her trenchant coterie equally keenly—but Hardwick’s parodies usually meant you were worth the attention. Apart from such glancing references, Hardwick is a notable omission from the book. I wonder if her extremely distinctive prose, with its tart precision and metaphoric extravagance, might have raised the matter of style more pressingly than Dean is willing or able to consider—of which lapse, more below.

Dean is perceptive and revealing about the paths by which women were able to establish themselves as critics and essayists in the decades after the war. They were apt (Parker, McCarthy, Hardwick too) to find themselves reviewing theater at first, not fiction. They might risk certain polemical adventures—McCarthy, Kael, and Renata Adler all wrote early pieces about the dismal state of criticism—but still find themselves relegated to writing about interiors, domestic or emotional. It’s instructive that Didion and Nora Ephron, for instance, excluded from their first essay collections a lot of articles written on conventionally female topics, and in relatively conventional registers. For years afterward, Didion nursed (until she published) the story of a Life editor who refused to send her to Saigon on the grounds that “some of the guys are going out.”

In its retelling of such histories, Sharp is a timely and acute book. You have to wonder, however, about how much work a term like “sharpness” can be made to do, and what it distracts us from. In her preface, Dean explains that all twelve writers, including those like West and McCarthy who were radical when young, found political or social activism to be inadequate or restrictive; her implication is that real writing involves some abjuring of action in the name of ambiguity, doubt, and subtlety of opinion. I suspect some of the women in Sharp may have demurred at that. And the distinction raises the suspicion that others in this period (black writers, feminist writers) might have been “sharp” in some of the same, and many different, ways. In the end the question is something like: What is the value of having an artfully written opinion above having a deeply held principle?

There are good answers to that question, and Dean gives us some of them: Parker’s antic undercutting of ideological postures—“You old Duce, you”—or Didion’s suspicion of consoling narratives. (“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” The point is they don’t work.) But Dean is not the closest of readers, and so we don’t get much feeling for how these modes of skepticism and ambivalence are made and expressed in language. It is one (very useful) thing to track the social, professional, and intellectual affinities between all twelve writers, and quite another to handle the hard matter of their amazing sentences. Has McCarthy’s coolness the same temperature as Didion’s? How is a Parker wisecrack put together, compared to Kael’s? These were all writers who cared madly about the condition of their copy, but Dean rather scants the “art” in her subtitle. The result is a book that seems valuable and contemporary at the level of argument, but oddly unengaged with its material.

Brian Dillon is an editor at Cabinet magazine, and teaches writing at the Royal College of Art, London. The US edition of his most recent book Essayism (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017) will be published by New York Review Books in September 2018. He is working on a book about sentences.