Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

In a Man Booker long-listed novel, three sisters inhabit an isolated island.

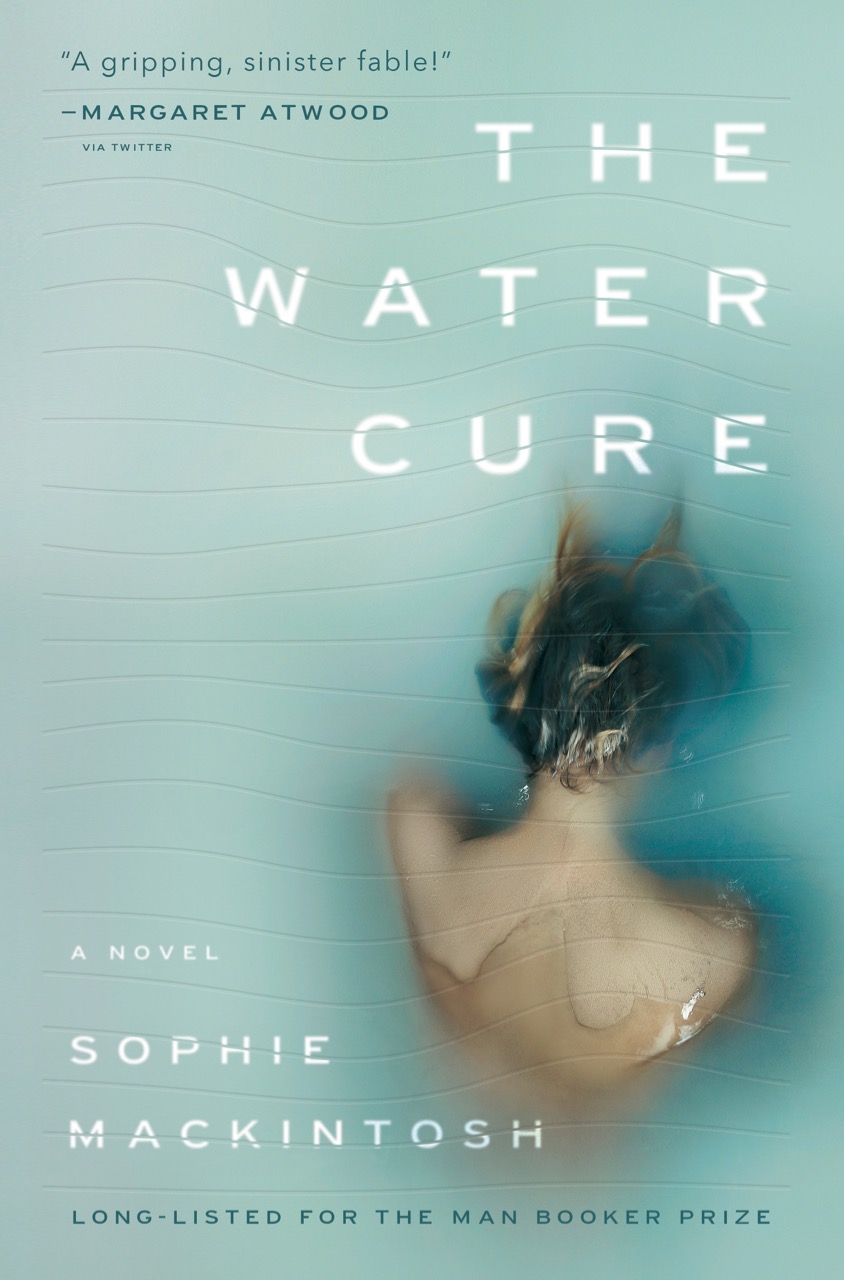

The Water Cure, by Sophie Mackintosh, Doubleday, 269 pages, $25.95

• • •

“O brave new world / That has such people in’t!” At the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Miranda relishes the idea of quitting at last her island home for an unknown realm of beauty and becoming. A dangerous desire, because whether we are playing at comedy or tragedy, the risk is that a new world order is already infected with the violence and corruption of the old. The Water Cure, the first novel by British writer Sophie Mackintosh, lifts some basic plot detail from The Tempest—island redoubt ruled by paranoid father, storm-tossed strangers come to threaten his power—but its shrewdest borrowings are a fever for metaphor and a shivery moral uncertainty. The novel, rapturously received on its UK publication in May 2018, and long-listed for the Man Booker Prize, is edgily aware of the history of utopian and dystopian fiction, and how one can easily become the other.

The Water Cure is narrated by three sisters: Grace, Lia, and Sky. We never learn their ages; Grace is certainly an adult, Lia perhaps late adolescent, and Sky the pubescent “baby.” They live on an unnamed island, in a large decaying white house where their parents have formerly received and treated “damaged women” from the mainland—deliberately damaged by men, that is, and by a mysterious toxicity men carry inside them. It is supposedly to protect their daughters from men, and from their poison, that the sisters’ parents have been torturing them all their lives. The girls are sewn into “fainting sacks,” made to play a perilous “drowning game,” and forced to drink salt water until they vomit. Their mother contrives rituals in which her daughters must kill small animals—drown a mouse, burn a toad—or physically hurt each other. They learn to be violent, and to temper their emotions: “You could cut yourself on the sharpness of our disregard.”

At the start of the novel the father, also known as King, has vanished, presumed dead. Grace is pregnant with his child, and later speaks to his absence: “What it was like to be in love with you: fucking awful, even after you revealed it was technically all right.” The mother’s rituals both express and thwart familial grief; she shrouds her daughters in muslin, stops their mouths, puts up signs around the house: “No more love!” But one morning after a storm there are three figures on the shore, two men and a boy. A long central section of The Water Cure is told by Lia, who falls in love with one of the men, Llew. “I know that without being touched I will die,” Lia says of him. But also: “I debate the sort of small accident I could orchestrate that would keep him close to me.” It’s unclear who is in the greater danger.

In its pursuit of perilous ambiguity, The Water Cure has the quality of a folk or fairy tale. Are Lia, Grace, and Sky, as their father once insisted, examples of “a new and shining kind of woman?” Have the rigors of their seclusion turned them into brilliant creatures, mythic feminist avengers, bred by a patriarch to repel patriarchy? Or are they instead monstrous victims of a familial cult, deluded into hate and fear of the world beyond their island’s coast? The Tempest is one source of the novel’s elemental indecision. But Mackintosh has drawn too from a certain literary history of dangerously isolated adolescence. There are whispers in The Water Cure from William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and Iain Banks’s The Wasp Factory—though as if those glib tales of violently diverted boyhood had been rewritten by Angela Carter, the English prose magician of feminist appropriation.

At the level of its language, Mackintosh’s novel is something else again: a book so saturated with intense and unsettling imagery that its sentences feel like face-fulls of polluted sea spray. In places Mackintosh is just luridly metaphorical: a stillborn child resembles a glass paperweight, physical or emotional trauma is like a poison that leaches into hair, organs, blood. Or her prose is satisfyingly rhythmic and at the same time semantically untethered: “Our world is made up of humid air over rough sea, rip tides theoretical and deadly, birds that hew the sky with their ominous bodies.” (Theoretical and deadly?)

At their most achieved, however, Mackintosh’s sentences are strict, cool containers for a variety of organic or atmospheric disintegrations. The air crackles, skin withers, the mind bristles like the onset of a migraine; when Lia parts the curtains to look at the sea, she is “amazed not to see the water full of limbs.” In contrast to this language of uncanny bodily disarray—you could make comparisons with the recent work of Ben Marcus—the male visitors to the island speak only in clichés, as if their mouths have frozen in the shapes and attitudes of patriarchal banality. Llew, Lia’s lover, asks if she is “taking precautions,” tells her they have “a good thing going on,” angrily announces that he does not belong to her. If their tyrant father was right, and a poisonous maleness menaces the three young women, it seems the toxin may be language itself with its sinister, laughable simplicities: “It’s terrible to be a man, sometimes.”

In the shape of its narrative, The Water Cure is less extraordinary than in its texture. There is a predictability to the novel’s violent conclusion, as it mimics and reverses the closing scenes of The Tempest. Perhaps this comes with the literary territory: island stories end either with rescuers on the horizon or dark deeds in the interior. The very form of dystopian fiction, if it’s to function as parable or allegory, depends on narrative insularity, even circularity. In The Water Cure, we are never sure if the outside world is better or worse than the island, or just the same: a place of extreme violence constantly denied by a language that is all lies. Still, other stories come to the surface: the voices of the “damaged” who speak in italicized inter-chapters—“All that had been needed was permission for everything to go to shit, and that permission had been granted.” Which is also to say that Mackintosh has written a novel that feels sorely of its time.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction is published by New York Review Books. He is working on a novel and a book about sentences.