Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

From fashion houses to slaughterhouses: the work of photographer

Dora Kallmus.

Madame d’Ora, installation view. Image courtesy Neue Galerie. Photo: Hulya Kolabas, 2020.

Madame d’Ora, Neue Galerie, 1048 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through June 8, 2020

• • •

Editor’s note: As of this writing, the Neue Galerie is temporarily closed to the public due to COVID-19 concerns.

• • •

Dora Kallmus, born in 1881 to a prominent family of the Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna, defied all expectations for a young woman of her standing. Rather than marry, have children, and perhaps pursue a stimulating hobby, she adopted the name Madame d’Ora and launched a wildly successful career as a photographer.

But her fascinating story, as illuminated by the five decades of work on view in this new survey at the Neue Galerie, curated by Monika Faber, is not one of a disinherited black sheep: Kallmus was a famously charming socialite who used her proximity to aristocracy, fashion, theater, and the artists of the European avant-garde to tremendous professional advantage. It was only late in life, in the wake of WWII’s unthinkable devastation, that she turned to the macabre imagery that would inspire Jean Cocteau’s florid description of her career. “Madame d’Ora, fanned by the wing of genius, strolls in a labyrinth whose minotaur goes from the Dolly Sisters to the terrible bestiary of the slaughterhouses.”

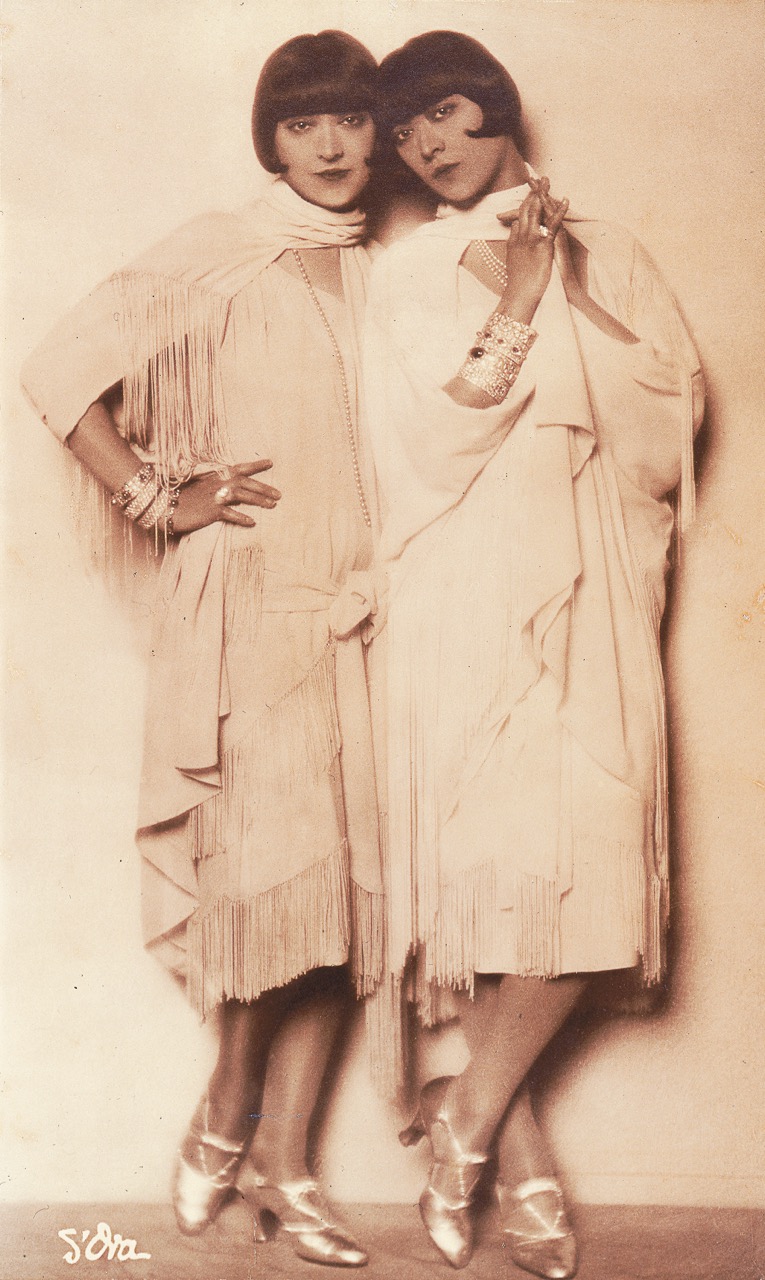

Dora Kallmus, The Dolly Sisters, ca. 1928–29. Image courtesy the Jewish Museum.

The Dolly Sisters were Hungarian-born stars of stage, transfixing paragons of roaring twenties glamour and scandal, but I think it’s fair to say that Kallmus’s glittering images of the twins are, as photographs, nothing special. With regard to this edifying show, it’s good to keep in mind, so as not be disappointed (which I was, a little), that Atelier d’Ora—in both its Viennese and Parisian incarnations—was a high-volume commercial studio. And while many of the photographer’s subjects, from Gustav Klimt to Josephine Baker, made radical contributions to the art of their time, Kallmus’s depictions of them were not necessarily innovative, and were not meant to be. While I believe the exhibition’s wall text when it touts her fresh, informal approach as distinct from the conventional portraiture of her day, some of the differences noted may be too nuanced to register a century later.

Dora Kallmus, Entertainer Josephine Baker, 1928. Photo: © Nachlass Madame d’Ora, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

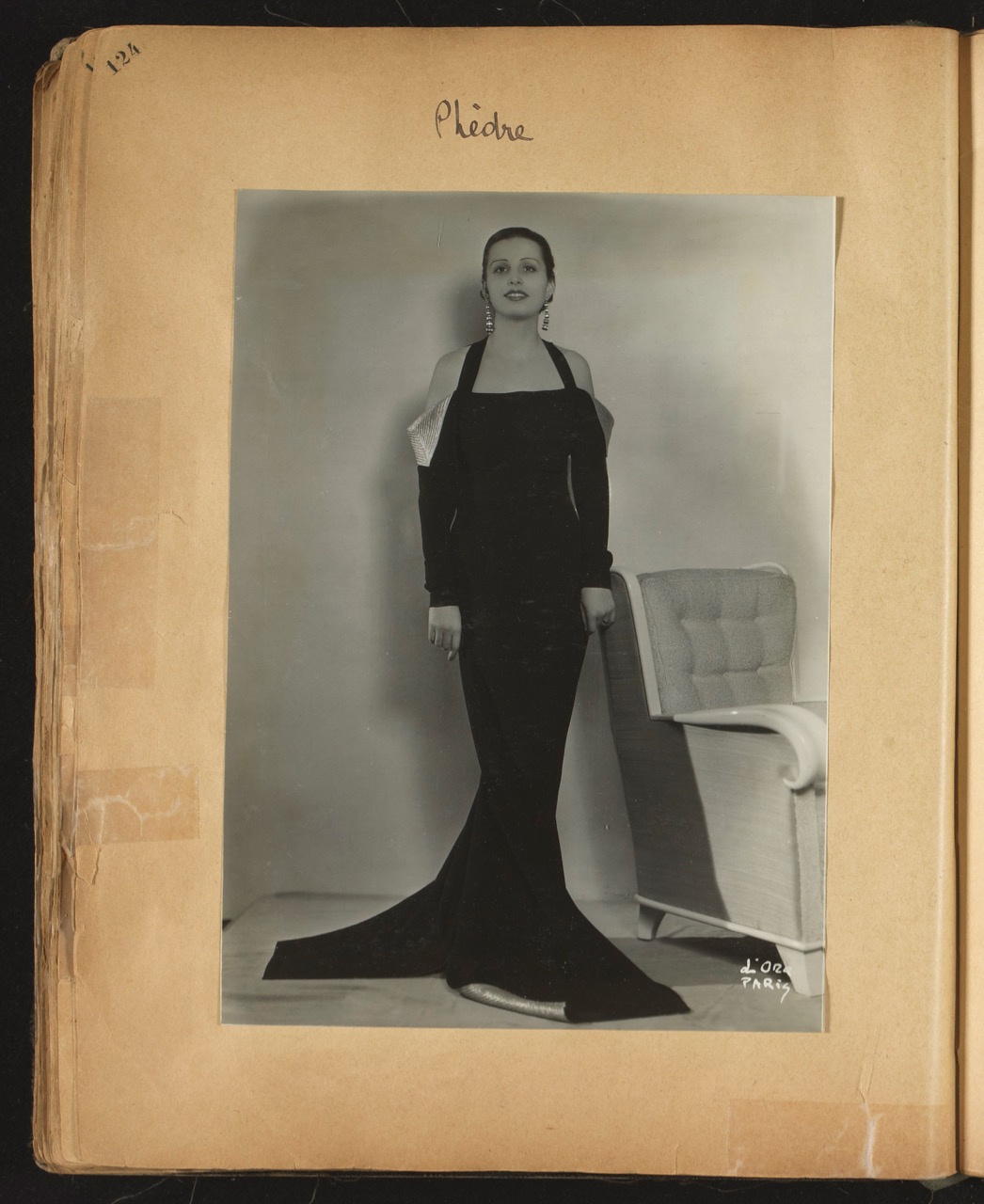

Or perhaps her amazing, more adventurous images (there certainly are some) get lost in the deluge of workmanlike photos. A parade of her magazine covers, which mark the medium’s transition from illustrations to photos, is interesting as ethnography (and provides an opportunity to marvel at Kallmus’s ascendance as a woman in interwar Europe); an album for the fashion house of Lanvin (1931–37) is exquisite—mainly for its dresses.

Dora Kallmus, Lanvin studio album: “Phèdre” dress, 1933. Photo: © Patrimoine Lanvin.

Madame d’Ora holds court on the third floor, where rotating exhibitions complement the museum’s illustrious collection of twentieth-century art and design from Austria and Germany, whose crown jewel is Klimt’s Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907). The 1914 former mansion, which was commissioned by industrialist William Starr Miller and later occupied by Grace Vanderbilt after the death of her husband, is an appropriately stately New York home for it: the portrait of a Viennese businessman’s wife, overwhelmed by decorative patterning in gold and silver leaf, shines brighter for its architecturally sumptuous environs, as well as its nearness to the kind of elegant Vienna Secession and Wiener Werkstätte furnishings that would have filled the apartment of a wealthy and fashionable Jewish family such as the Bloch-Bauers. This was Kallmus’s world, too—if you pass through the Galerie’s second floor before you go upstairs, you’ll be primed to feel the gilded ambience latent in her early black-and-white prints.

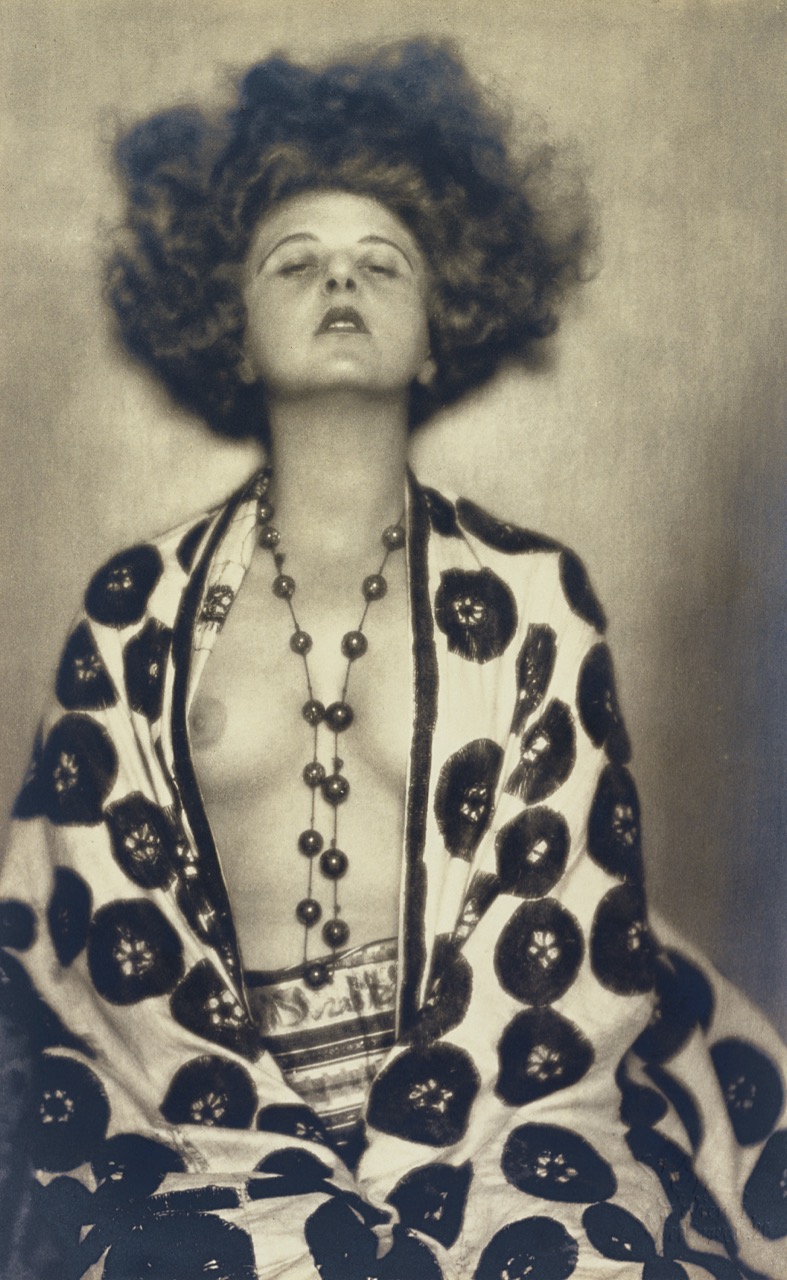

Dora Kallmus, Actress and dancer Elsie Altmann-Loos, 1922. Image courtesy Photostudio Setzer-Tschiedel.

Despite its uneven work, the show is a pleasure, with each of the galleries painted a rich gray, and a narrow passageway off the grand staircase serving as a walk-through timeline. The large room devoted to Kallmus’s output from 1908 to 1923 offers parallels as well as correctives to the constrained image of Adele. In contrast to Klimt’s sickly elongation of his subject and jewel-box background, we see many of Kallmus’s women as protagonists of Viennese modernism, who, like the photographer herself, found at the turn of the century a window of opportunity to thrive artistically—before their milieu was dispersed by Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938. The painter Mileva Roller, composer Alma Mahler, and gallerist Emma Bacher were all subjects, and a 1922 portrait of actress and dancer Elsie Altmann-Loos is one of the exhibition’s most iconic pictures. In a rare action shot, she throws her head back, hair flying, breasts partially exposed beneath a Jugendstil-print wrap. And, of course, there are Kallmus’s self-portraits: she appears as an intense unsmiling character, always with a beautiful little dog.

Dora Kallmus, Self-portrait with her dog Miss Penny, ca. 1928. Photo: © Nachlass Madame d’Ora, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

The Yorkshire terrier Miss Penny is featured frequently after she was discovered in a Paris pet shop. Kallmus’s extensive magazine work spurred her to relocate full-time to the fashion capital in 1925, though she continued, for the next decade, to regularly visit her sister Anna (who was also unmarried) at the home they had purchased together in Frohnleiten, south of Vienna, and which they christened Haus Doranna. Countless photos from this period—of actresses and dancers in designs from Chanel, Balenciaga, Schiaparelli, and others—speak to Kallmus’s ability to coax expressive performances from her subjects, and show her employing more formally daring approaches, including the use of novel sets. A moody 1937 image of a model in a boldly appliquéd crêpe-de-chine dress by Raphaël has her seated, in pensive profile; a painted portrait by Léonard Foujita of French writer Tristan Bernard towers in the background. But by then the end of such inventive shoots was nigh. With the onset of the war, fashion work—and indeed, all magazine work for a Jewish photographer (even one who, like Kallmus, had converted to Catholicism)—would dry up.

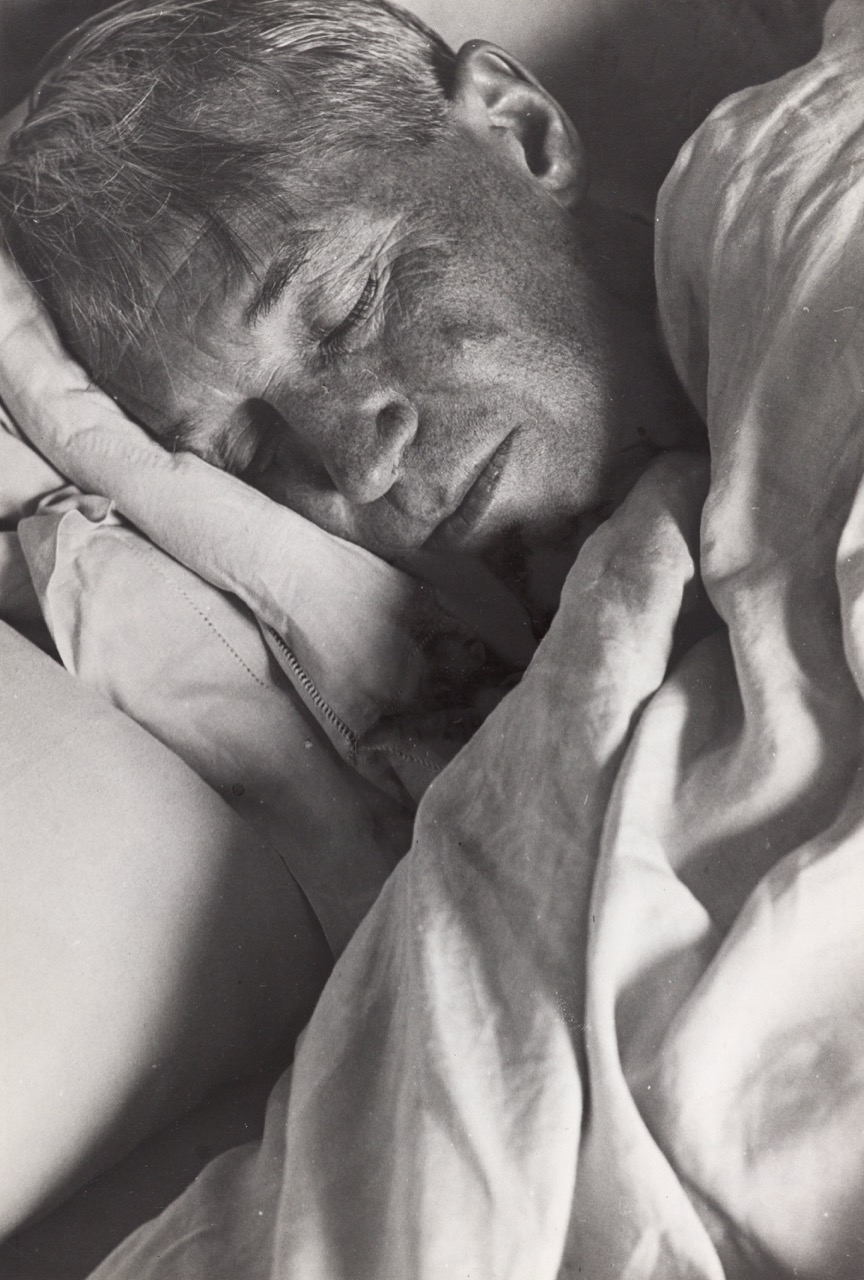

Dora Kallmus, Maurice Chevalier sleeping, 1955. Photo: © Nachlass Madame d’Ora, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

Living in exile near Lalouvesc in 1942, she wrote in a letter to Maurice Chevalier, a lifelong friend whom she had first worked with in Vienna, “Like a crazy woman, this little d’Ora left Paris thinking everyone would know who she was . . . But there are two worlds, and I was only familiar with one of them, the one perfumed with luxury and flowered with orchids.” Haus Doranna had been seized by the Nazis, and she would soon learn that Anna was dead, almost certainly murdered at Chełmno.

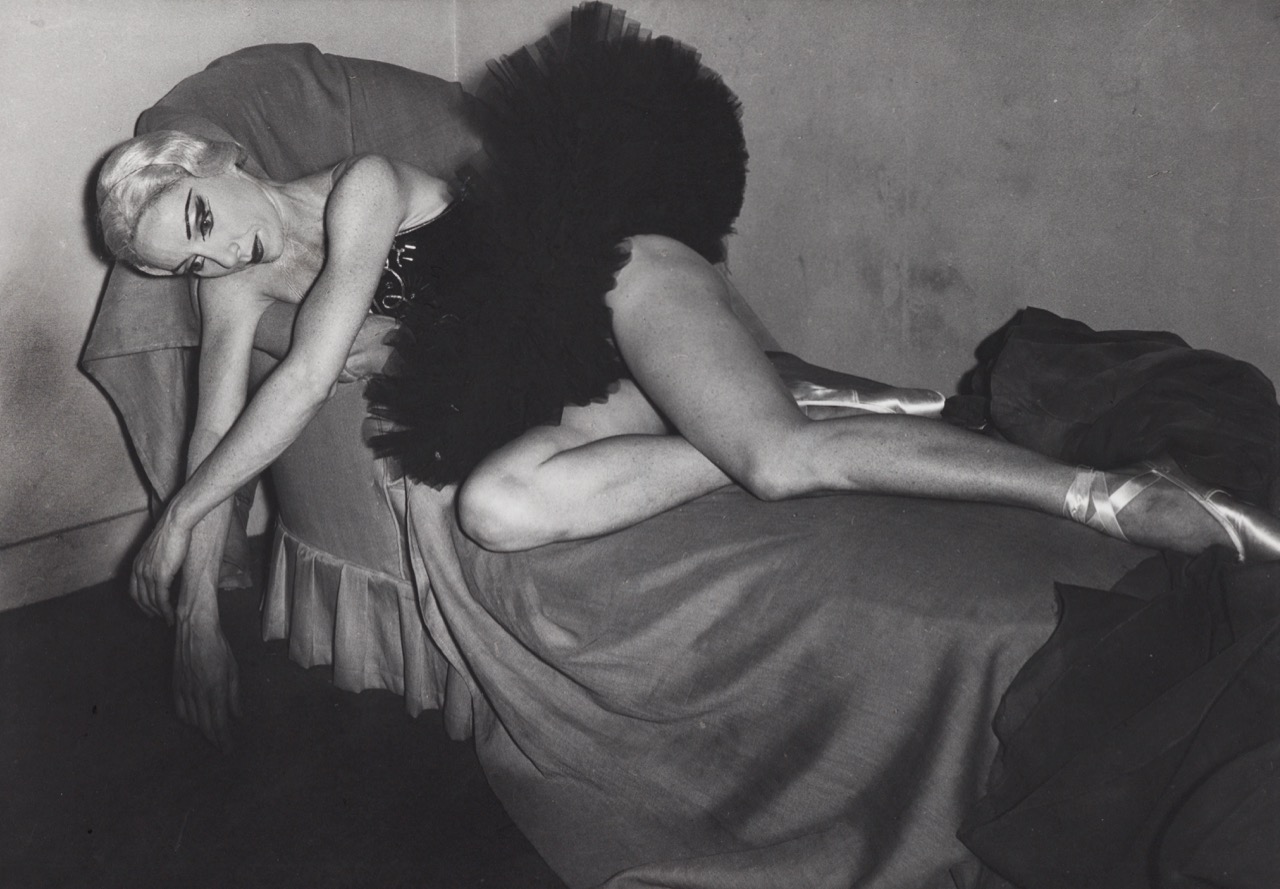

Dora Kallmus, Dancer Rosella Hightower of the Cuevas Ballet in costume, 1955. Photo: © Nachlass Madame d’Ora, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

What Cocteau spoke of was not really a pivot from celebrities to slaughterhouses, but something even stranger—a brilliantly incongruous, uncalculated simultaneity of subject matter. Kallmus had begun to experiment with a lightweight Rolleiflex when first forced to abandon her atelier, never returning to studio photography. With no semblance of her previous career, she developed a new, verité, sometimes darkly absurdist aesthetic. The results are striking—her 1955 image of Chevalier sleeping is the best of the many pictures of him she took; her shot of Rosella Hightower of the Cuevas Ballet, collapsed in costume, blank-faced on a daybed, perhaps her best of a dancer.

Dora Kallmus, Severed cow’s legs in a Parisian abattoir, ca. 1954–57. Photo: © Nachlass Madame d’Ora, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

At the same time, during the fifties, as she explored this new kind of society photography, she visited Parisian abattoirs, capturing images of quotidian death with mournful and appalled precision. Arresting scenes—such as the lonely severed head of a calf, face up, with a trail of dark blood for a body, or a line of seven clipped-off legs, standing on their hooves against a dirty wall—are evidence of her new acquaintance with an unperfumed world. The pictures, more than a footnote, are a startling coda to an effervescent career. They make you see all that comes before them a little differently.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.