Ed Halter

Ed Halter

After Metamorphoses puts Ovid in motion.

Installation view of Amy Sillman: After Metamorphoses at the Drawing Center. Photo: Martin Parsekian.

Amy Sillman: After Metamorphoses, the Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, New York City, through March 19, 2017

• • •

If the recent spate of monstrous transformations wrought upon our national body politic have left you feeling queasy, painter Amy Sillman’s exhibition at the Drawing Center might provide some tonic. It’s a five-minute, action-packed animated movie based on Ovid’s mythographic epic, which Sillman aptly titles After Metamorphoses (2015–16).

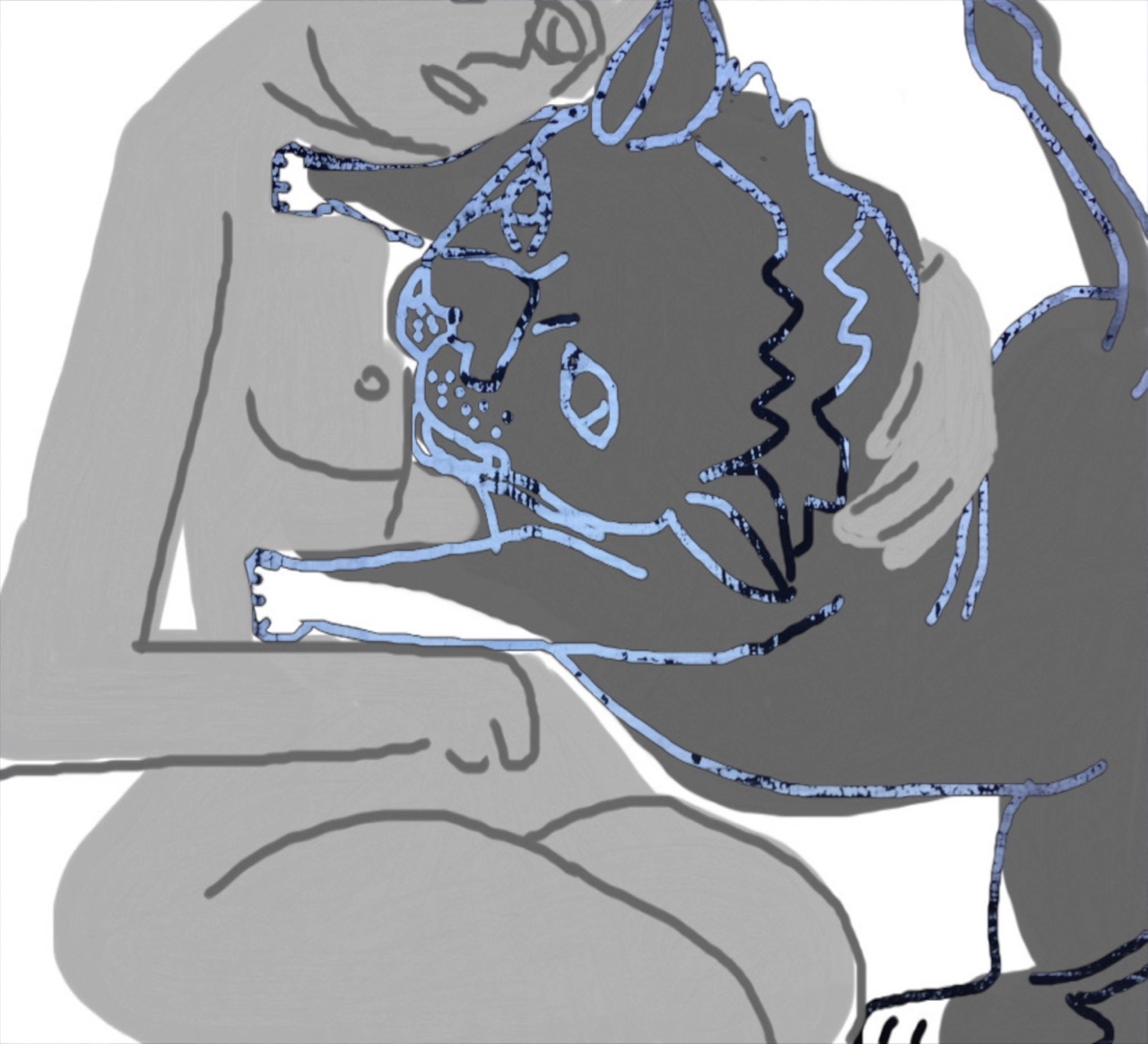

In the Roman poet’s account, hundreds of gods and humans transmogrify into multifarious animals, vegetables, and minerals, often as acts of divine vengeance, and Sillman’s complex cartoon consists of a dizzying visual catalog of these mutations. Some of the more famous instances can be recognized in the video—Juno placing the slain giant Argus’s eyes onto the tail-feathers of the peacock, for example—but many of the continuously fluid events in After Metamorphoses are far more elliptical and enigmatic: a bird’s silhouette reshapes itself into that of a galloping horse, which then becomes a bearded man crouched over his cane; a maned lion suckling at a woman’s breast rapidly turns into a crane, and then into a snake, and then into a tangle of snakes overlooking the Earth’s globe.

Amy Sillman, After Metamorphoses, 2015–16. Video animation with iPad drawings, 5 minutes. Music by Wibke Tiarks. Image courtesy the artist.

While Ovid’s Metamorphoses has provided the basis of countless artworks since it was first published some two thousand years ago, such renderings have typically depicted discrete moments, frozen mid-narrative; consider Bernini’s sculpture Apollo and Daphne (1622–25), in which the god grasps the nymph even as her legs begin to grow into a laurel’s trunk, or Titian’s canvas Diana and Actaeon (1556–59), showing the instance when the doomed Actaeon stumbles unwittingly onto the divine huntress’s hidden bathing site. As a painter, Sillman could have likewise isolated a single Ovidian tale. Instead, her choice to inventory the Metamorphoses via cinema resists the poem’s traditional deployment as fodder for emblem and allegory, stressing the nonstop act of transformation itself, experienced here as a chaotically endless loop.

Sillman has been making what she likes to term “animated drawings” only in the last six or so years, though she has incorporated elements of cartooning into her paintings and works on paper for much longer. She employed user-friendly consumer tech to create her earlier moving-image efforts, like Triscuits (2010–11), made from ink drawings shot on her iPhone, or Pinky’s Rule (2011), which she drew with fuzzy finger-lines using a free iPhone app. In exhibitions, these animations have been displayed on small screens that recapitulate the modest scale of their making.

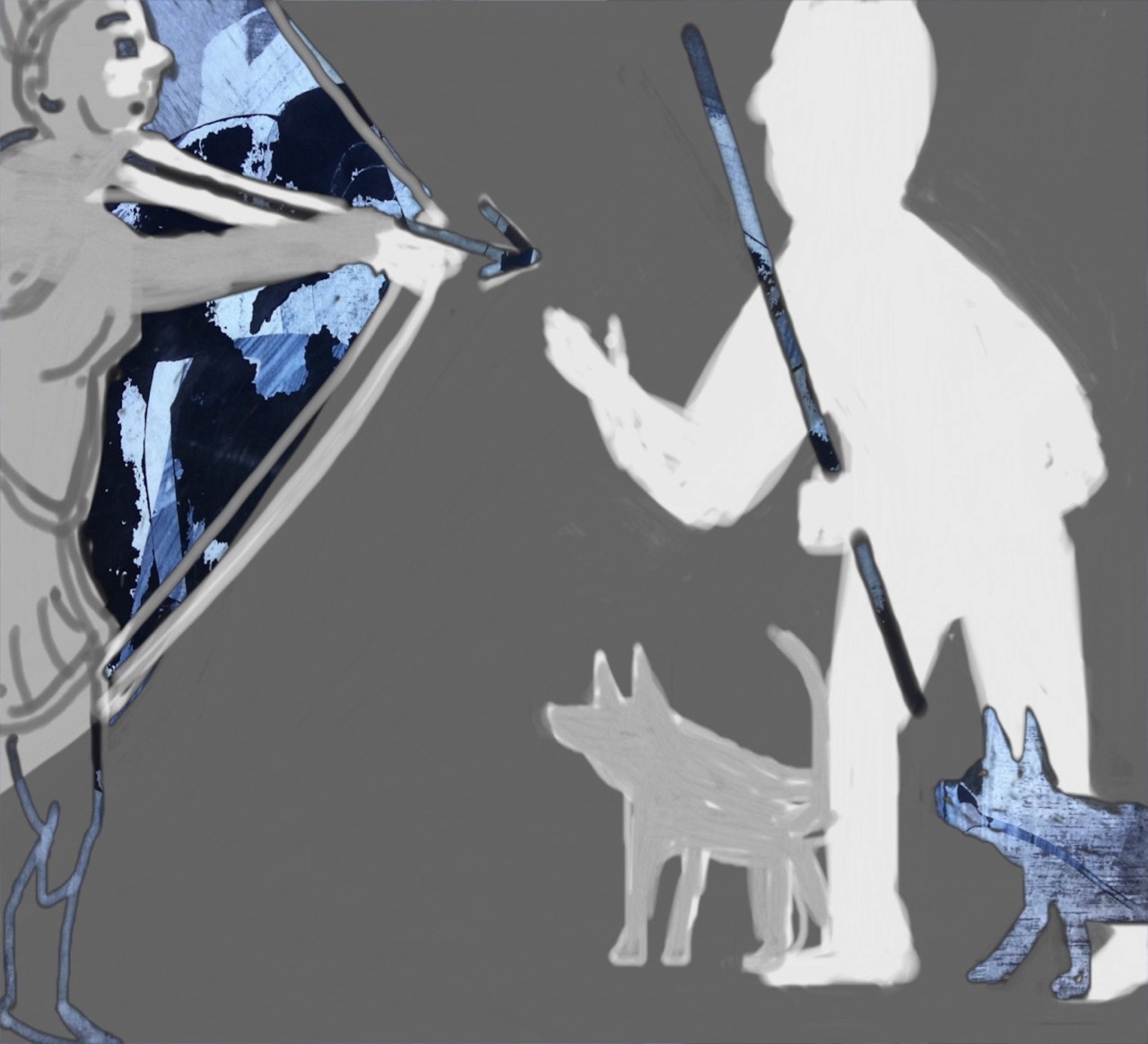

Amy Sillman, After Metamorphoses, 2015–16. Video animation with iPad drawings, 5 minutes. Music by Wibke Tiarks. Image courtesy the artist.

After Metamorphoses, her most complex and ambitious animated drawing to date, uses both photographed ink compositions and touch-screen sketches, layered and chroma-keyed together at various scales; at the Drawing Center, her movie is given its own room, where it is projected about six feet high on the wall. Such an expansion engenders wild shifts in magnitude. The high-definition video allows us to view the rich analog and digital textures of each image, seeing drippy copper- and bronze-colored washes of pigment juxtaposed against the softly pixelated edges of a gesture-rendered streak. Though her work, here as elsewhere, evokes a melancholy sense of the comedic, Sillman is a painter whose deeply engaged approach to movie-making is no joke. If some visual artists have historically turned to motion pictures in order to create something quickly and automatically—Raymond Pettibon’s punky low-fi videos of the 1980s come to mind, for example—Sillman has always taken the opposite route, choosing instead a labor-intensive, painstaking process that pays careful attention on the level of the individual frame.

Moreover, in choosing Metamorphoses as her subject matter, Sillman participates in animation’s longstanding exploration of weird bodily change, used to humorous effect in the very first frame-by-frame animated film, Émile Cohl’s stick-figure dreamscape Fantasmagorie (1908). As Cohl discovered, metamorphosis is one of animation’s fundamental possibilities, visualizing an alternate world in which any object becomes infinitely fungible. This tendency has continued throughout the practice’s history, from Felix the Cat’s detachable, magical tail and the Fleischer Brothers’ utterly elastic characters, up through later twentieth-century kiddie-TV like Barbapapa and The Herculoids. Writing in 1945, Hungarian film theorist Béla Balázs noted that cartoons like Felix transpired within “that amazing world of which the prime mover and omnipotent ruler is the pencil or paintbrush. The substance of this world is the line and it reaches to the boundaries that enclose the graphic art.” Balázs declared that “in the world of creatures consisting only of lines the only impossible things are those which cannot be drawn.”

Amy Sillman, After Metamorphoses, 2015–16. Video animation with iPad drawings, 5 minutes. Music by Wibke Tiarks. Image courtesy the artist.

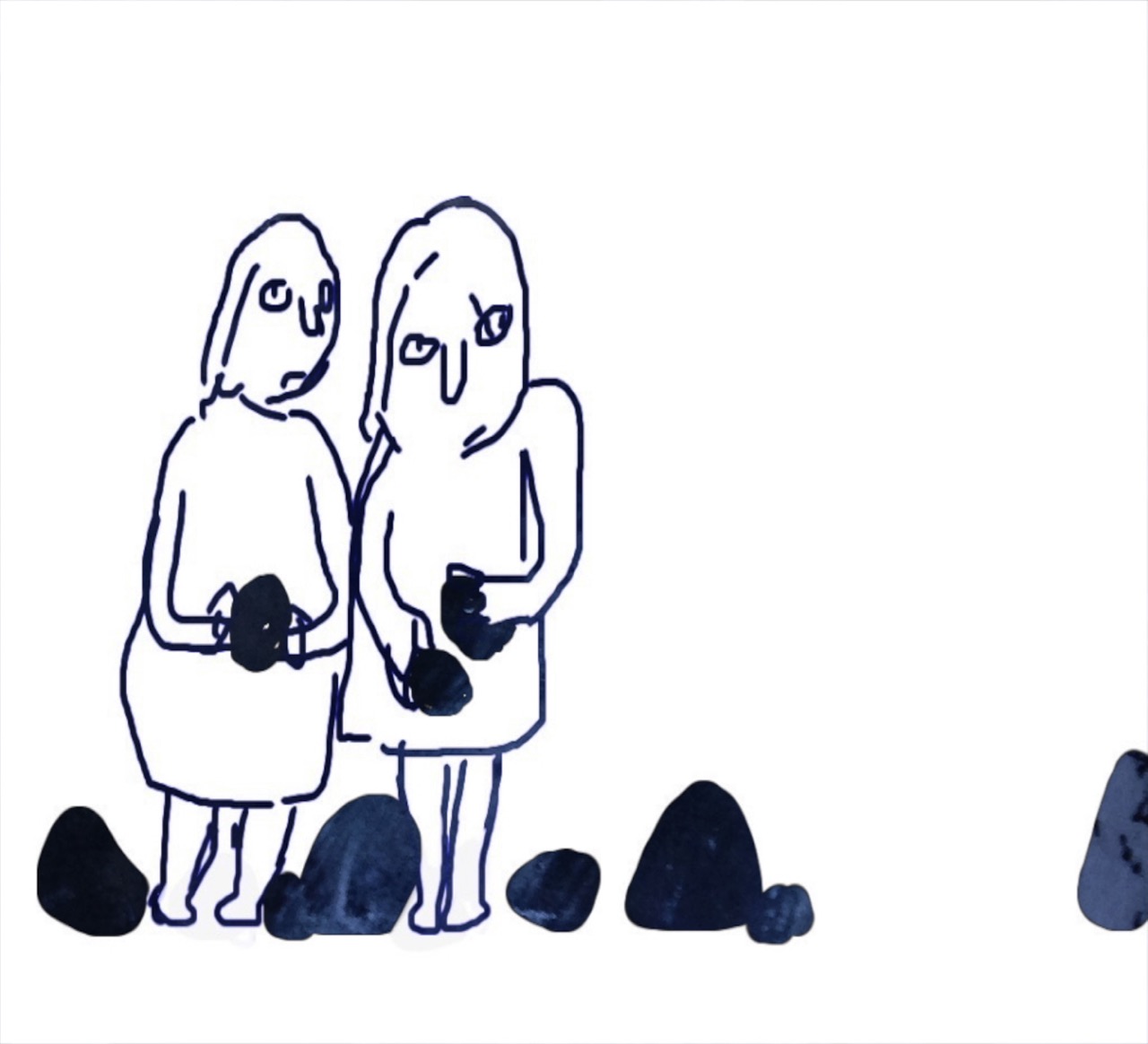

Sillman herself has often spoken of the “lump” as one of her preferred formal tropes, materializing in her work as schlumpy humanoid bodies and asymmetrical abstract shapes. The Sillmanian lump appears throughout After Metamorphoses as the intermediate state between transformations, as in the video’s opening seconds, when two people pick up earthy blobs from the ground and toss them into the next scene, where they morph into warring human beings. This sequence takes its inspiration from Ovid’s cosmogonic story of Pyrrha and Deucalion, the only two survivors of a world-spanning deluge, who repopulate the planet by throwing stones over their shoulders, which then become a new race of people. In Sillman’s version, the regenerated human race turns to conflict immediately in the midst of its own resurrection, blending death into birth and then, with little hesitation, moving on to the next transfiguration.

In a zine produced to accompany After Metamorphoses, and made available at the Drawing Center, Sillman notes that her movie would first show “on the literal eve of an inauguration” as “we face a global rise of neo-fascism”—a messy moment of chaos, indeed. One balm for this turmoil, Sillman suggests, could be art’s own protean nature. “We haven’t figured it out but we love art that offers change above all,” she writes. “Insistent, unremitting change that won’t resolve into finality or finesse.” In this context, Sillman’s morphing lumps take on an ambiguously hopeful valence, offering some comfort, at least, in the certainty of endless instability.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, The Believer, frieze, Mousse, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.