Ed Halter

Ed Halter

Fascist humanoids and crawling puddles of slime: futurist film fantasies at the Japan Society.

Gamera 3: Incomplete Struggle. © 1999 Kadokawa Corp.

“Beyond Godzilla: Alternative Futures & Fantasies in Japanese Cinema,” the Japan Society, 333 East Forty-Seventh Street, New York City, through April 8, 2017

• • •

The first images in the American cut of Ishiro Honda’s The H-Man (1958) are two widescreen shots of a mushroom cloud; they appear to be created from scientific test footage, tinted flame-orange, rumbling across the frame to a tense string composition—a blunt reminder of the Atomic Age’s destructive genesis. Honda is best known for his iconic Godzilla, in which the eponymous reptile is made gargantuan by US testing in the Bikini Atoll, and as its opening sequence indicates, The H-Man, too, centers on malevolent and bizarre mutations. In this case, contamination from a hydrogen bomb blast engenders deadly phase-shifting creatures who alternately appear as crawling puddles of slime or vaguely anthropomorphic specters. These weird life-forms lurk in the sewers of Tokyo, blending into the dark fetid waters. They attack by enveloping their victims and liquefying their bodies, leaving only an empty pile of clothing behind.

The H-Man. © 1959 Sony Pictures.

It’s apt that Japan Society will screen the US version of The H-Man to kick off its series “Beyond Godzilla: Alternative Futures & Fantasies in Japanese Cinema,” curated by Mark Schilling, a Tokyo-based film critic for Japan Times and author of The Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture. As its title indicates, the program showcases lesser-known examples of Japan’s robust tradition of tokusatsu, or special-effects-driven films, a genre that came into its own with the international success of Honda’s Godzilla, and argues that these films contain significant traces of political consciousness, wrapped within ostensibly escapist fantasy. And while the long string of fan-beloved kaiju movies, starring Honda’s towering creation and its enormous city-stomping compatriots like Rodan, Gamera, and Mothra, have ensured global renown for Japanese studio Toho’s decades-long franchise, “Beyond Godzilla” reveals a much wider range of styles and scenarios. The H-Man, for instance, plays less like a monster movie than a moody crime thriller, following tenacious local cops through shadowy streets and mobster-filled nightclubs as they investigate a string of murders that lead them both to the mutant killers and a ring of drug smugglers.

The H-Man’s use of special effects—designed by Honda’s longtime collaborator and Godzilla co-creator, Eiji Tsuburaya—is relatively sparing and more evocative when compared to the disaster-laden kaiju films. The H-Man shares Godzilla’s radioactive themes, but it eschews the wholesale destruction of Honda’s earlier film in favor of more fundamentally existential terrors, reminding us of radiation’s unsettling ability to rearrange matter on a microscopic scale. In liquid form, the creatures move much like the alien goo in the contemporary American B-movie The Blob, glimpsed in the darkness as some mysterious gelatinous substance rapidly dripping sideways toward its prey. Other times, they vaporize into ghostly green superimpositions, their ectoplasmic bodies warped and refracted, as if struggling to retain coherence.

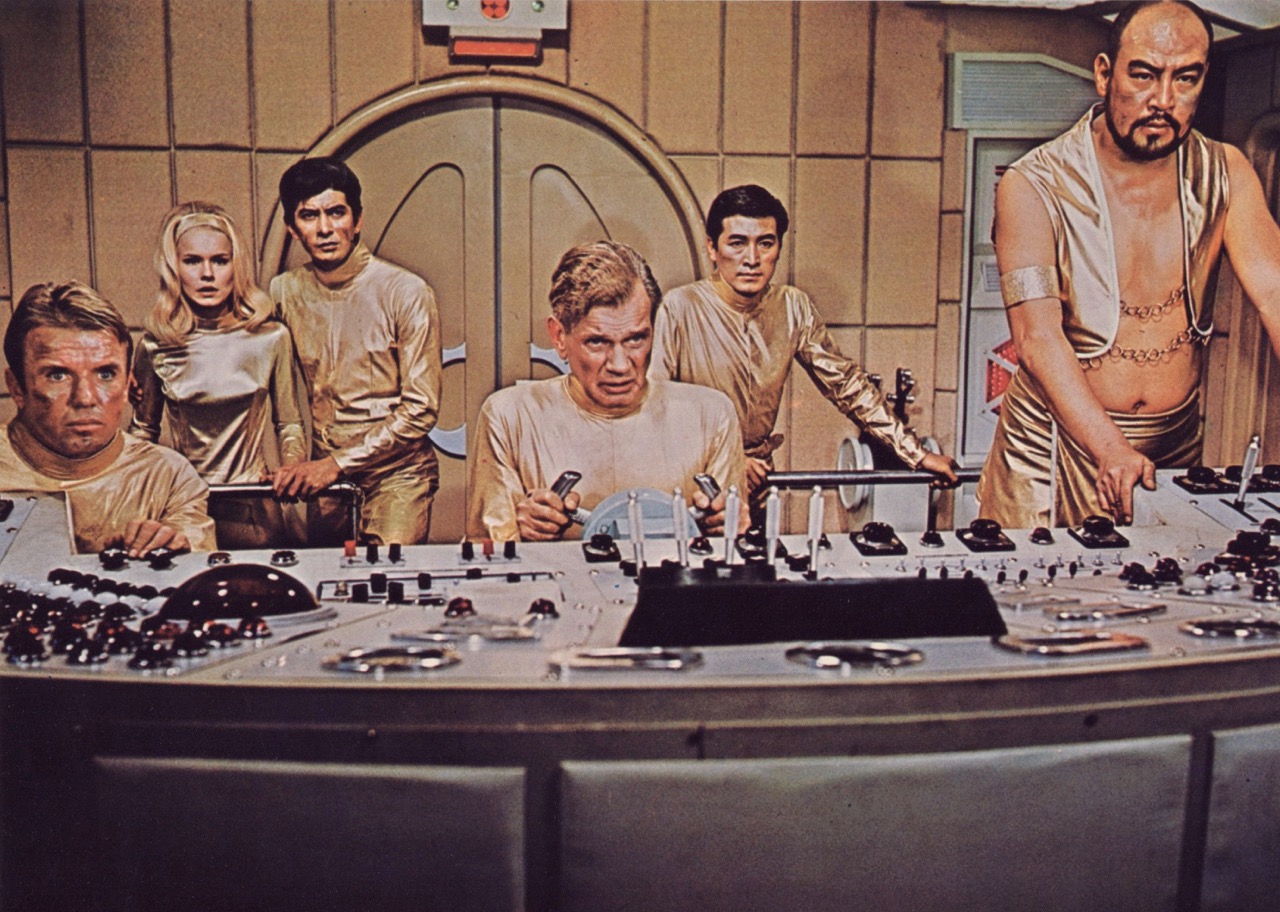

Latitude Zero. © 1970 Toho Co. Ltd.

In contrast, Honda-Tsuburaya’s vibrant, campy aquatic adventure Latitude Zero (1969) dives into spectacle, employing copious use of analog effects, miniatures, and monster suits, shot primarily on soundstages decorated with boxy, blinking computer panels and groovy comic-book colors. The look is very Barbarella-on-a-budget, and as with Roger Vadim’s film (released the year prior), Latitude Zero is an international production, shot in English in Japan with American and Japanese actors. Aging Hollywood leading man Joseph Cotten, then past sixty, plays McKenzie, the two-hundred-year-old captain of the wondrously Jules-Verne-esque submarine Alpha, commanding his ship while decked out in a queeny ensemble of puffy-sleeved jacket over bare chest, accented with a wispy, lime-green neck kerchief. McKenzie and his crew deliver a trio of rescued bathysphere researchers to the undersea city of Latitude Zero, where many of the world’s top scientists have fled to live in a perfectly rational society devoid of money, crime, and mortality, thriving beneath the rays of an artificial sun. “Politics are only needed by people incapable of running their own lives,” Cotten’s character explains, as an eternally youthful Latitudian in gold-lamé jumpsuit bounces giddily on a trampoline behind him.

Thankfully for the sake of plot, there are villains afoot. Captain Kroiga (scene-chewing Hiraku Kuroki), clad in dominatrix black, complete with riding crop, helms a rival submarine that attempts to destroy the Alpha in some dreamily gauzy underwater battle sequences. Meanwhile, an evil power couple, the cape-clad Dr. Malic (Cesar Romero) and his bouffanted co-baddie Lucretia (Patricia Medina, fresh off The Killing of Sister George), scheme to destroy Latitude Zero. A Dr. Moreau-style mad scientist, Malic splices animals and people together into chimeric monstrosities—man-bats, an eagle-winged lion—designed to do his bidding.

Released in the wake of such big-budget efforts as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes, Latitude Zero must have seemed cheap and hokey even in its own time, its heavy-handed techno-utopianism harking back to older sci-fi films like Forbidden Planet and Things to Come. Today, viewers might still chuckle over Latitude Zero’s naiveté—until we ask ourselves whether it is a good thing that we no longer allow ourselves the pleasures of such optimistic fantasies.

Blue Christmas. © 1978 Toho Co. Ltd.

Yet the overt moralizing of Latitude Zero raises further questions about how critics and cinephiles have long positioned the value of science-fiction cinema. Many of the other films in “Beyond Godzilla” bear social commentary secreted within tales of alien invasion and futuristic inventions. Kihachi Okamoto’s moody Blue Christmas (1978) explores the lives of characters whose blood has been turned blue by UFO visitations; the newly transformed become a stigmatized minority, and must deal with the psychological consequences of their demoted status. The faintly erotic School in the Crosshairs (1981), directed by Nobuhiko Obayashi, takes place on a campus invaded by fascist humanoids from outer space. The teen heroine’s battles against authoritarianism will resonate with those of us in the twenty-first century, but the film’s stylized pastel cityscapes and mind-meldingly phantasmagoric optical-effects finale suggest that its social message might be a mere MacGuffin, the rush of visual stimulation providing the primary aesthetic punch.

The Secret of the Telegian. © 1960 Toho Co. Ltd.

The Secret of the Telegian (1960) seems to stress this point in its introductory scenes. Directed by Toho stalwart Jun Fukuda with effects again by Tsuburaya, its titular secret is the discovery of “teleport-telekinesis” by a group of researchers, but the film opens at a fairground, where a barker entices visitors to enter a “Cave of Horrors.” As the camera follows fairgoers inside the cavern, we too are assaulted by a variety of shoddy but effective scare-ums like painted wooden demons, masked actors, and a dragon with blinking light-bulb eyes. Here Tsuburaya seems to be commenting on his own craft, linking his own celebrated cinematic creations to an older tradition of lowbrow entertainments whose own potent pleasures require no political justification.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, The Believer, frieze, Mousse, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.