Ed Halter

Ed Halter

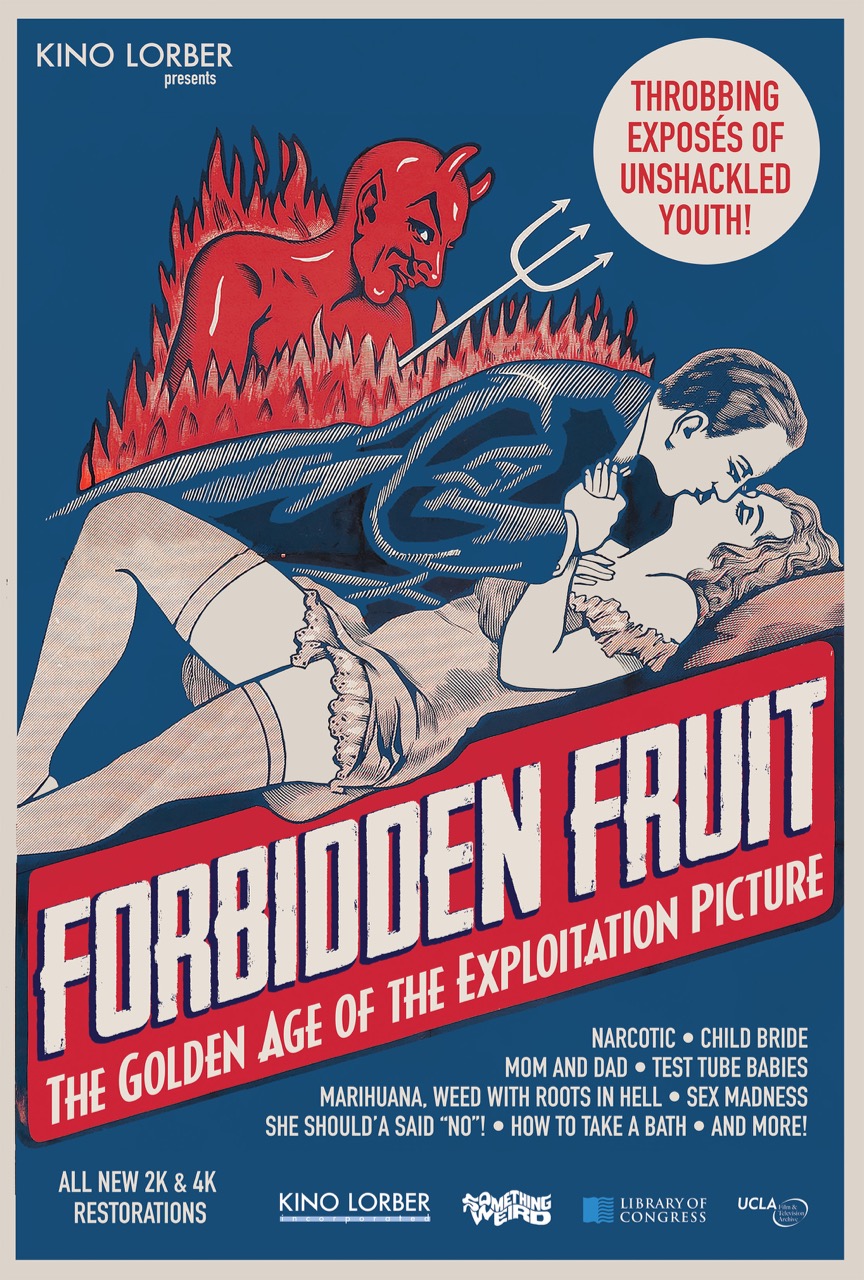

Narcotics, child brides, sex madness: a series revives seven early exploitation movies.

“Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Picture,”

Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, through

March 30, 2019

• • •

American independent cinema, the story usually goes, began after the middle of the twentieth century, when the decline of the old studios, the spread of television, and eventually the eruptions of the counterculture allowed a range of pioneers like Shirley Clarke, Roger Corman, John Cassavetes, Russ Meyer, Stan Brakhage, and Jonas Mekas to emerge. For many of these figures, independence primarily meant rejecting commercial concerns in order to elevate the art of cinema; in some cases, it was more about exploiting the entertainment industry’s lingering prudishness to lure thrill-seeking audiences away from the domesticating TV set. Yet far less attention has been paid to an earlier independent era: the ragtag generation of filmmakers who created and distributed exploitation movies outside the Hollywood system in the 1930s and 1940s, the scandal-chasing predecessors to Meyer’s nudie-cuties and Corman’s groovy acid trips.

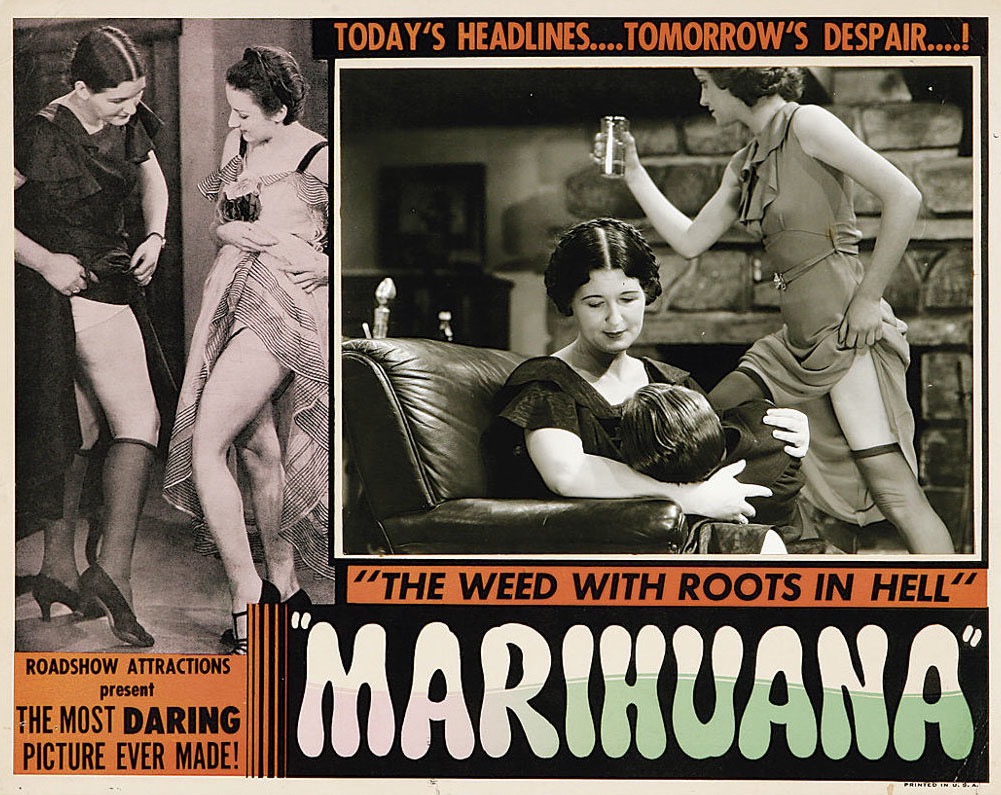

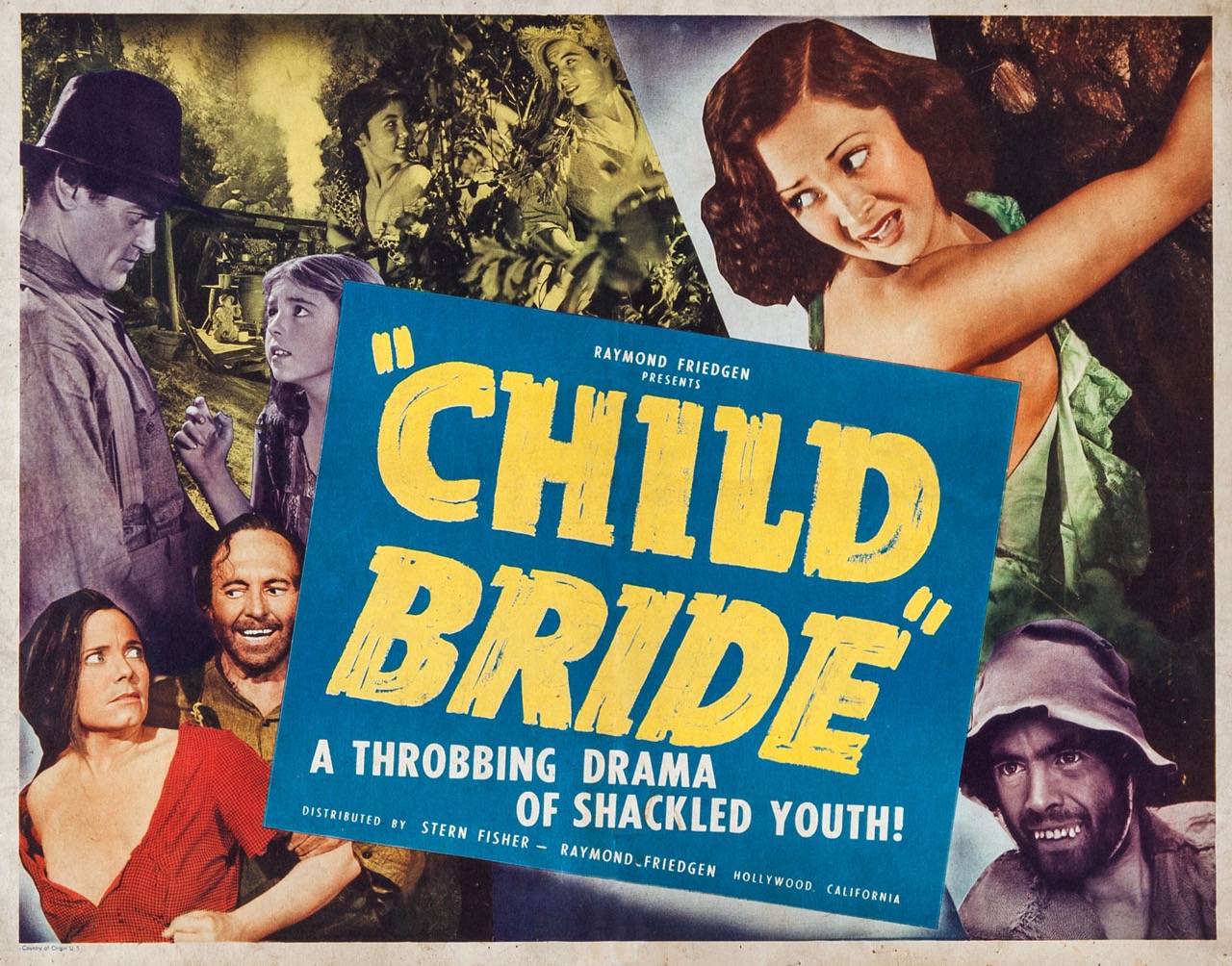

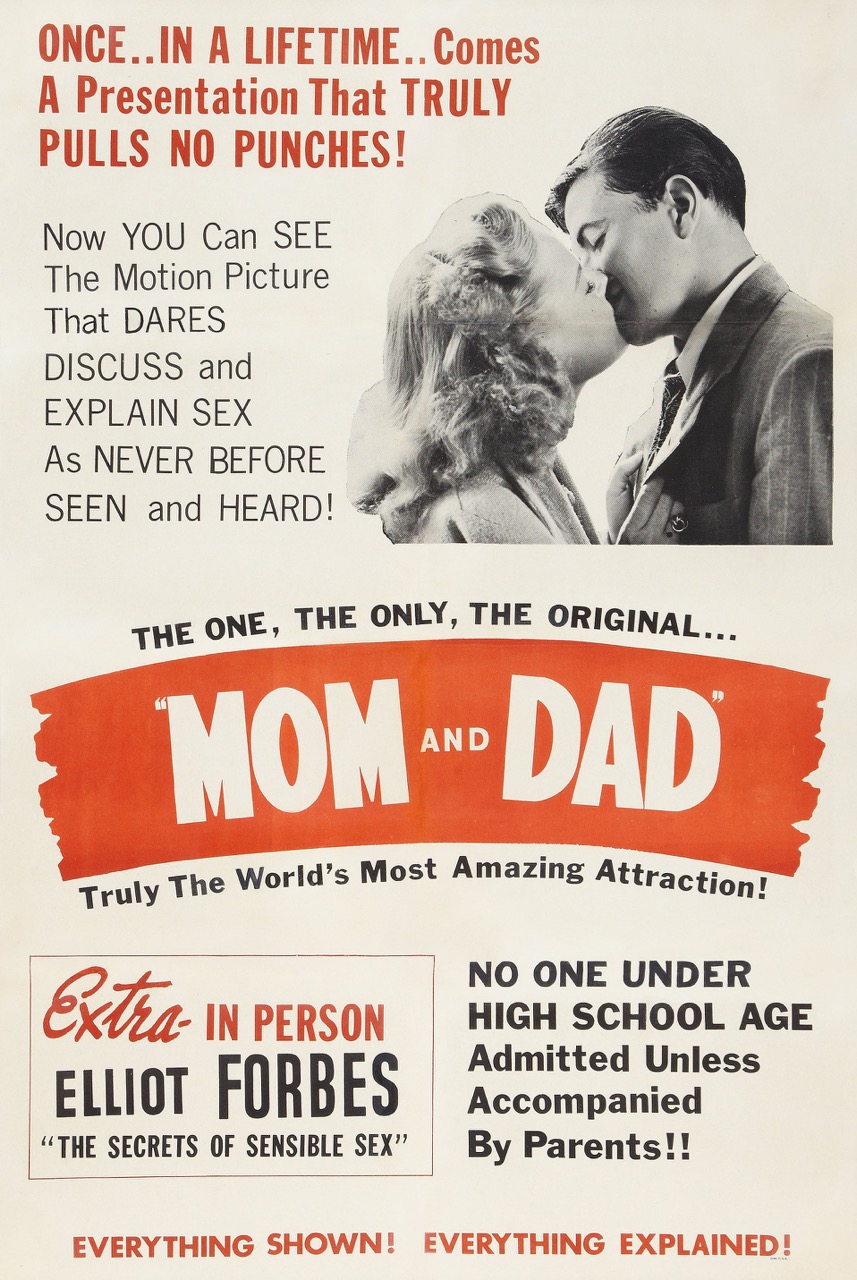

Cinematic cousins of the lurid fictions found in the era’s thumb-staining pulp magazines, exploitation films from the first half of the twentieth century trafficked in the tawdry and the taboo during the height of Hollywood’s Motion Picture Production Code, which began self-enforcement in 1934 after a slew of silent-era scandals. Brazen showmen of the period such as Kroger Babb, Dwain Esper, and others delighted and disgusted audiences with sensationalist titles like Narcotic (1933), Marihuana: Weed with Roots in Hell (1936), Child Bride (1938), and Sex Madness (1938), all produced on minuscule budgets—lower even than those of the serials and B-movies of Los Angeles’s Poverty Row companies. At the time, Hollywood’s monopoly meant that the big studios not only made and distributed the majority of films but also owned the largest theater chains, and could strong-arm most independently owned cinemas into booking their products exclusively. Nevertheless, cities and towns across the country typically had at least one second- or third-run movie theater, often in a struggling neighborhood, that had no qualms about screening a less-than-respectable picture if the allure of its adults-only content might attract a paying audience. Herein the exploitationeers found their own grimy niche, employing the ballyhoo of the carnival sideshow and the burlesque house to drum up sales, often traveling “road-show” style with 35mm prints in hand.

This month, Film Forum in New York revives seven of these once-controversial features, shown in new high-definition digital restorations, under the banner “Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Picture,” curated by writer and director Bret Wood, whose 1999 book of the same name, coauthored with Felicia Feaster, provides a lively historical introduction to the genre. Sex and drugs dominate Film Forum’s lineup. Esper’s Narcotic and Marihuana and the Sam Newfield–directed She Shoulda Said “No!” (1949, also released as Wild Weed) offer over-the-top dramatizations of opioid and cannabis use, while Harry Revier’s Child Bride, W. Merle Connell’s Test Tube Babies (1948), the anonymously directed Sex Madness, and William Beaudine’s Mom and Dad (1945) tempt viewers with archaic takes on human reproduction.

The pleasures of viewing these films today undoubtedly involves some cross-historical rubbernecking: audiences will chortle at outdated slang and marvel at risqué subject matter absent from Hollywood productions of the same era, like brief shots of female nudity or raucous depictions of cocaine-snorting and joint-smoking. Such was the rationale behind the revival of Reefer Madness (1936, not included in the series) for the midnight-movie crowd in the 1970s and VHS tapeheads in the 1980s. One of the more risible conventions of the genre is the attempt at providing a veneer of respectability through moralizing narration or the inclusion of fatherly physician characters to explain the perils of venereal disease, sex out of wedlock, heroin use, or what have you. “This picture is presented in the hope that the public may become aware of the terrific struggle to rid the world of drug addiction,” Narcotic’s opening title cards somberly declare. “We sincerely dedicate this picture to those who have worked with unceasing effort and given freely of their time to this cause.” As Wood and other historians have noted, these aspects are remnants of exploitation filmmakers’ efforts to mollify local censor boards (and perhaps the consciences of moviegoers themselves) by marketing their films as socially uplifting, educational fare.

Still from Narcotic. Image courtesy Film Forum.

Beyond the opportunity for easy laughs, however, early exploitation films give us disjunctive aesthetic experiences that can be profound. These are films of utter desperation, not merely in their often abject subject matter, but in their very form, with sundry elements struggling to coalesce into a coherent visual narrative. Amateur acting, unsubtle lighting, and poor print quality add an accidentally documentary-materialist vibe to such weird old artifacts. At certain junctures, their scandalous fictions melt away, and we are left staring at the grubby interior of a prewar honky-tonk or canvas-tented carnival. Trapped in the longueurs of off-tempo editing and oppressive room tone, we wonder about the unchronicled offscreen lives of the men and women who are doing their best to portray hop-head teenagers and tough-talking party girls.

Still from She Shoulda Said “No!”. Image courtesy Film Forum.

Many of the movies pad out their running times with a generous use of stock footage from scientific films and old silent melodramas, precipitating dreamy shocks of cut-rate surrealism, inadvertent versions of an oneiric Joseph Cornell montage. A sequence might lurch unexpectedly, as in Narcotic, from original scenes filmed by Esper in the 1930s to muddy, over-duped images of a car crash, purloined from junked reels shot a decade earlier. Elsewhere in Narcotic, we suddenly wander through what seems to be the darkened chambers of a traveling circus’s reptile zoo: the ramshackle cages are illuminated by a harsh spotlight from the cameraman, which stops briefly on a scrawny white cat, calmly eating an unidentifiable scrap of flesh under the lamp’s brutal glare. It’s a stunningly strange moment, in which the soothing fantasies of the silver screen completely dissolve, leaving only fragmented mirror-memories of all-too-real life.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was recently published by Seven Stories Press.