Ed Halter

Ed Halter

Video, dance music, and Felix the Cat: British artist Mark Leckey explores the metaphysics of mass culture at MoMA PS1.

GreenScreenRefrigerator, 2010–16. Image courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1. Photo: Pablo Enriquez.

Mark Leckey: Containers and Their Drivers, MoMA PS1, 22–25 Jackson Ave., Long Island City, through March 5, 2017

• • •

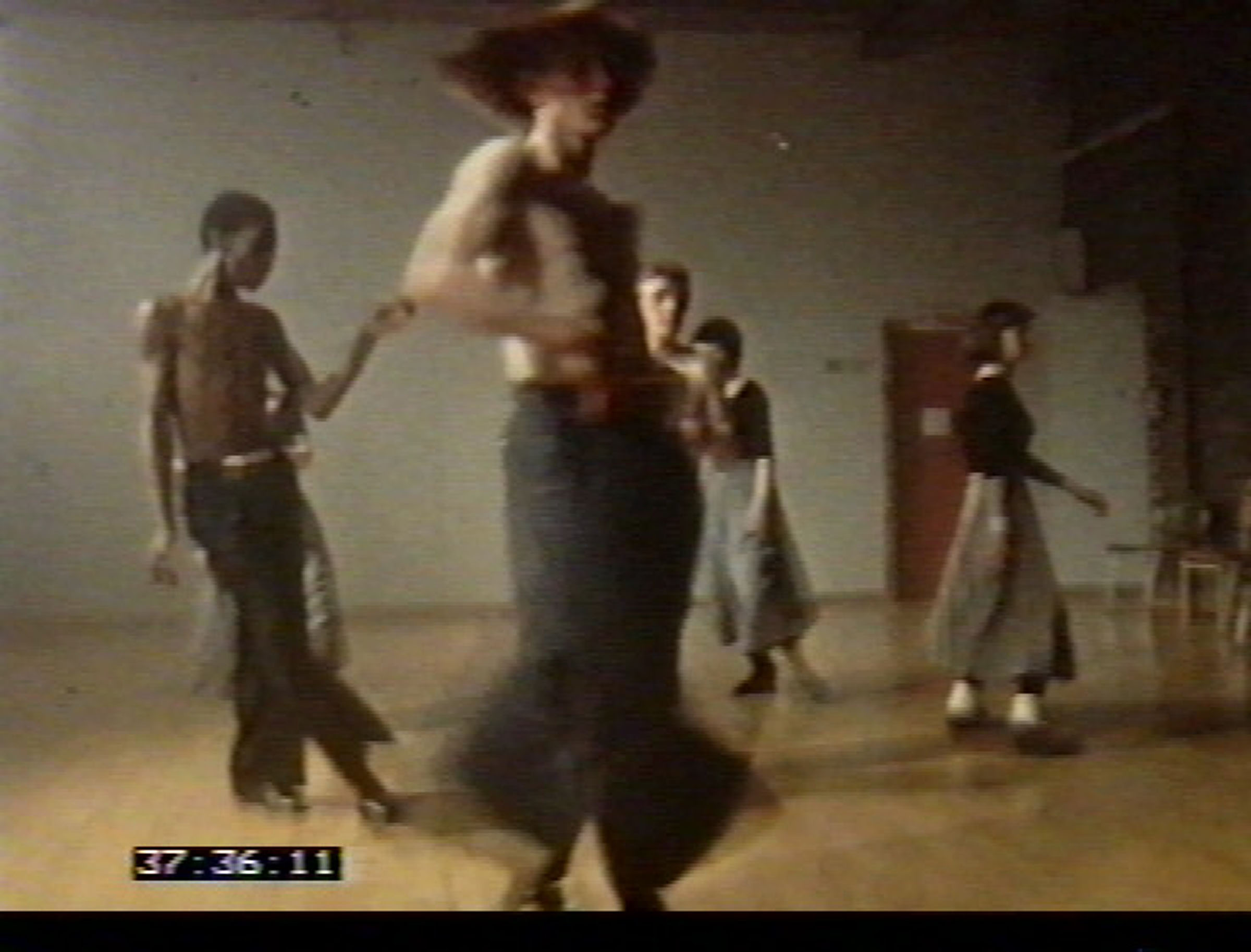

Despite the high profile that artist Mark Leckey has enjoyed in his native Britain for many years, he’s only now receiving his first substantial US exhibition with Containers and Their Drivers, a labyrinthine two-floor survey at MoMA PS1. On this side of the pond, Leckey remains best known for his 1999 found-footage video Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, a fifteen-minute compilation celebrating the history of British dance music from the 1970s to the 1990s, edited together from manifold obscure sources, obtained at great effort in the years before YouTube. At once ecstatic and auto-ethnographic, Fiorucci plays like a post-electronic update to Humphrey Jennings’s classic wartime documentary Listen to Britain (1942) for a generation that had moved on from music halls to nightclubs and raves, ideals of national solidarity long fractured into countless new tribal scenes. At PS1, Fiorucci enjoys its own shrine-like black-box room. Inside, his video is projected nearly floor-to-ceiling and flanked by two totemic audio speakers pumping out its bass-heavy music with such force that sound waves pulse through viewers’ flesh, dislodging dancefloor recollections of one’s own. The entrance to this dark cavern, secreted in the shadowy corner of another room, is easy enough to miss for those not seeking it—a nod, perhaps, to the more oblique circulation of subcultural knowledge as it existed decades ago.

Still from Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999. Image courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise.

Fiorucci remains a signature piece in this show not only because its breakout success brought Leckey wider attention. As early important works by artists sometimes do, it announced what would become the grand themes and chosen methods in his later career. Video is still a crucial part of Leckey’s practice—the many videos on view in Containers and Their Drivers, particularly Fiorucci, Cinema-in-the-Round (2006–08), and Dream English Kid 1964–1999 AD (2015), provide the keys to understanding the show as a whole, functioning in part as audio-visual manifestos. Leckey’s videos are produced through appropriation and remixing, and so too are his objects; the galleries are filled with sculpture-like and painting-like products of shopping and downloading, image-capturing and outputting. Leckey’s preoccupations recur throughout: the metaphysics of mass culture and its deep underground reverberations; the weirdly corporeal and emotional effects that relatively low-information phenomena like cartoons and techno beats are able to engender; and the erosion between personal and collective memories in an era when both are defined through our relationship to popular media.

Perhaps only in a survey such as this could the consistency of Leckey’s ongoing concerns become so clear, as the individual works don’t always speak so articulately in isolation. Indeed, it would be easy to saunter through Containers and Their Drivers and mistake Leckey for an altogether less complex artist, particularly if the videos are ignored. In his poker-faced installation GreenScreenRefrigerator (2010–16), for example, Leckey presents a black Samsung “smart” fridge, looming like the monolith from 2001 against a draped chroma key backdrop, along with a suite of other Samsung electronic devices from the same year, playing animations and performance documentation. Other rooms are filled with Leckey’s promotional posters and foam-board standees used to publicize past exhibitions and artist talks. Taken on their own, such objects could be read as mere commentary on the ubiquity of marketing and corporate branding, a topic that has been given more than its fair share of attention in recent art.

It’s only in the pinging of signals between the rooms that Leckey’s greater ambitions emerge. The videos especially are the active nodes in this network, their ideas, images, and sounds seeming to radiate outward from the black boxes into the galleries, producing games of correspondence from room to room. In one of PS1’s most cavernous spaces, five working speaker towers from his Sound System series (2001–12) are arranged like mini-ziggurats, bleating out sound effects and a playlist of jams from Fiorucci and other works. Dream English Kid includes the roar of Dr. Who’s time-traveling vehicle in its collage of British media from the 1960s onward, and GreenScreenRefrigerator showcases a video of its TARDIS-shaped Samsung appliance spinning in deep space. Dr. Who’s villainous Cybermen pop up as 3-D-printed sculptures in a permuted recreation of Leckey’s artist-as-curator turn The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things (2016), his wunderkammerish series of displays featuring original and recreated artworks, mechanical and electronic devices, and archaeological artifacts.

The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things, 2016. Image courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1. Photo: Pablo Enriquez.

His video Cinema-in-the-Round, created from an artist’s talk-cum-performance of the same name that Leckey gave at the Guggenheim and Tate Modern, functions as its own curatorial compendium of sorts, recapitulating Leckey’s work up to that point and including films by other artists ranging from the entirety of Hollis Frampton’s minimalist Lemon (1969) to clips from James Cameron’s maximalist Titanic (1997). Among Cinema-in-the-Round’s concerns is the venerable icon Felix the Cat, the movies’ first merchandized cartoon character, whom Leckey interprets as an emblem for the strange fungibility of media creations. “There is something about these drawings that is so thick and weighty that they become almost palpable,” Leckey says of Felix’s body in his video. “It’s like watching pure matter moving about.” Cinema-in-the-Round includes an old photo of a Felix-shaped balloon from some forgotten early-twentieth-century parade; this figure seems to come to life in the sculpture Felix The Cat (2013), whose enormous form is crammed into a room of its own, stooping downward like Alice grown gigantic in the White Rabbit’s house. Elsewhere, the cat is transmitted via early-twentieth-century television experiments in the video Felix Gets Broadcasted (2007), and just his tail appears, wagging enigmatically, for Leckey’s 16 mm loop Flix (2008).

Felix The Cat, 2013. Image courtesy the artist and MoMA PS1. Photo: Pablo Enriquez.

The most persistent character in Drivers and Their Containers is Leckey himself. Dream English Kid tells Leckey’s life story largely through footage found on YouTube or artifacts purchased on eBay, an effort to map the details of his own life onto the greater dispersion of media and ephemera in the world at large. It’s a gesture that could have become indulgent in the hands of another artist, but the piece is both stunningly mythopoeic and surprisingly moving. The artist’s life thus becomes a cybernetic matrix that invisibly connects every room in the show. Therein lies the primary tension in Leckey’s work, between overarching conceptual theses that comment on the nature of media and culture, and localized moments of nostalgia that might provide a more gut-level emotional response in the viewer, depending upon taste, generation, and geography. It is the conflict between the ideal smoothness of digital communication, and the unpredictable resonances generated between our analog selves.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, The Believer, frieze, Mousse, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.