Ed Halter

Ed Halter

A new suite of works from the “uncanny valley.”

Seth Price: Danny, Mila, Hannah, Ariana, Bob, Brad, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Seth Price: Danny, Mila, Hannah, Ariana, Bob, Brad, Museum of Modern Art PS1, 22–25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, New York, through September 3, 2018

• • •

Since his first exhibitions after the turn of the millennium, Seth Price has developed a reputation as something of an artist’s artist whose practice bridges the media-forward conceptualism of older figures like Joan Jonas or Dan Graham and the born-digital generation that has emerged after the rise of the internet. Quintessentially twenty-first century in his transdisciplinary approach, Price has made work over the past two decades using a wide range of means: musical compositions and pop mixtapes; videos and films; essays, books, and websites; paintings and drawings; sculptures crafted from laser-cut rare woods, screen-printed Mylar sheets, and vacuum-formed plastic casings; fashion and furniture. These manifold creations have been united not so much by any fixed formal concerns or sets of procedures, but rather a penchant for offering up riddles and enigmas, evoked through the use of visual tricks, logical brainteasers, ambiguous modes of production, or weird materials that simultaneously elicit fascination and repulsion. Price conveys this paradoxical sensibility through an often subtle antistyle that carefully hovers just at the edge of wrongness.

Seth Price, Danny, 2015. Dye-sublimation print on synthetic fabric, aluminum, LED matrix, 58 × 223 × 4 inches. © Seth Price. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

Such is the case with Price’s Danny, Mila, Hannah, Ariana, Bob, Brad (all 2015), a single suite of works currently on view at MoMA PS1. Installed in the museum’s airshaft-like, exposed-brick Duplex gallery, the six pieces at first appear to be a set of elongated digital screens, ranging from about twelve to nineteen feet high, hanging vertically on three walls. They glow with enormous images of pinkish-brown, topographically rich textures that resemble photographs of desert expanses shot by aerial drones, or algorithmically generated versions of the same. Danny displays a strip of glistening azure along its left edge that could be water, delineating some barren beachfront against a wider expanse of sandy shore. Grayish Ariana’s harsh pockmarked surface splays out across overlapping, hard-cornered segments that float against an abyss of pure black, as if some rough-hewn variation on Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion map had been used to depict the cratered surface of the moon.

Seth Price, Ariana, 2015. Dye-sublimation print on synthetic fabric, aluminum, LED matrix, 58 × 178 × 4 inches. © Seth Price. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

It only takes a moment of closer inspection to see that what look like video screens are actually light boxes covered with ultra-high-definition images printed on some sort of translucent material; it quickly becomes clear that the textures are not landscapes but extremely magnified portions of human skin. Miniscule wrinkles have been blown up into an intricate lattice of triangular intersections, concatenating across patchy fields of unevenly distributed melanin. The effect of this quasi-medical grotesque is reminiscent of the visit to Brobdingnag, the island of giants, in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels: witnessing a group of titanic maidens en déshabillé, the protagonist expresses not libertine delight but rather “horror and disgust,” since “their skins appeared so coarse and uneven, so variously colored, when I saw them near, with a mole here and there as broad as a trencher.”

Seth Price, Hannah, 2015. Dye-sublimation print on synthetic fabric, aluminum, LED matrix, 220 × 60 × 4 inches. © Seth Price. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

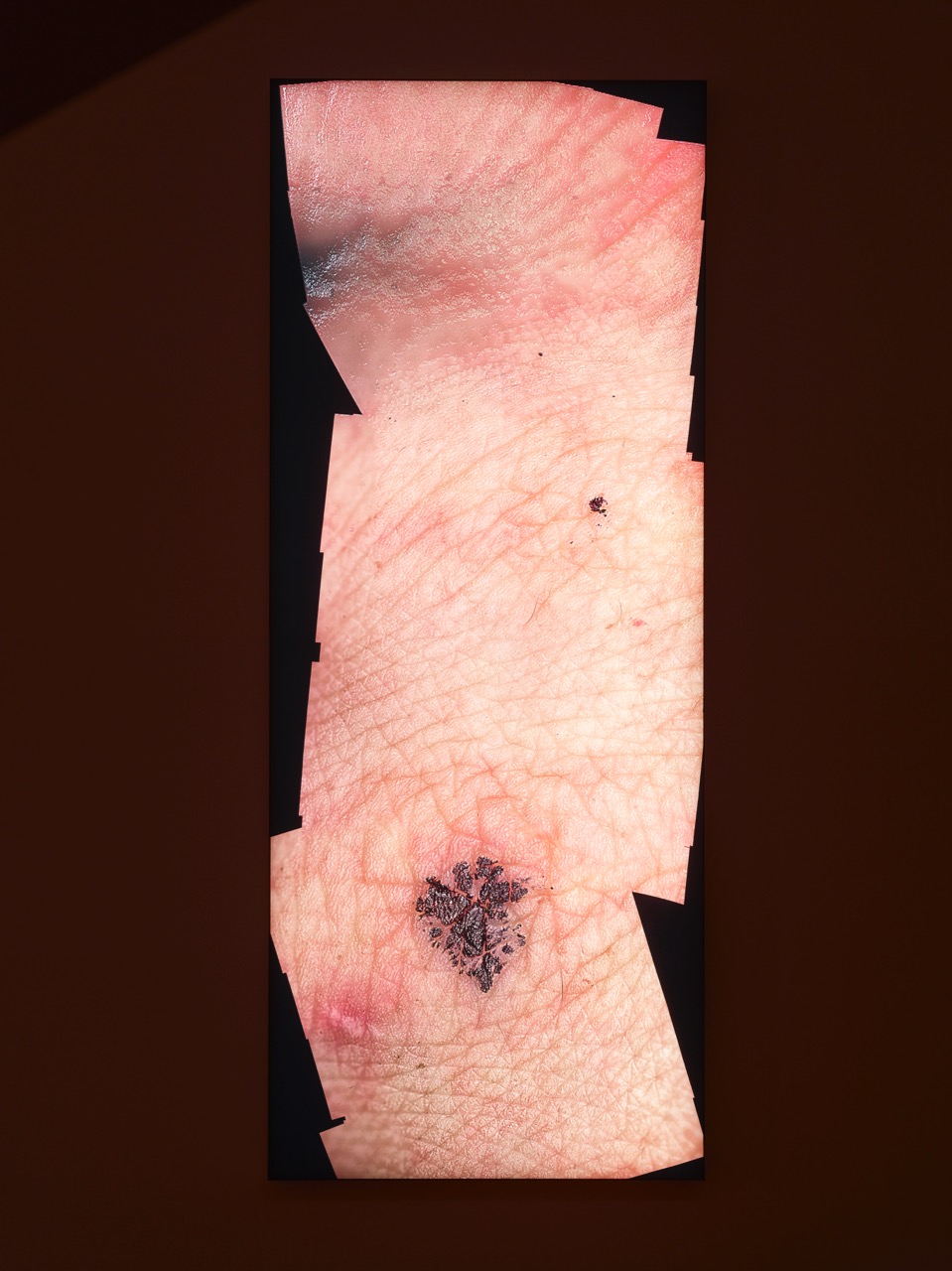

Seen so intimately, it’s difficult to tell which minute part or parts of the body have been photographed, aside from a few semi-discernable markers: the top portion of Hannah reveals what might be the edge of a palm, unfolding like the bloom on a broccoli stalk, under which faintly bluish streaks suggest veins running down a wrist; Brad displays an undulating crisscross of wrinkles against luminescent flesh, punctuated by a seemingly chitinous blood-black melanoma. Such speculative identifications are further frustrated by odd contourings that suggest the anamorphosis of digital image-mapping—similar to when a 3D rendering of an animated character’s face texture, for example, is viewed stretched out as a 2D rectangle.

Seth Price, Brad, 2015. Dye-sublimation print on synthetic fabric, aluminum, LED matrix, 58 × 146 × 4 inches. © Seth Price. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

The installation’s wall text threatens to spoil the sense of mystery by detailing the processes by which the work was made—as such didactics typically do. Here the question of whether the images were photographically recorded or digitally synthesized is answered: both. “Using a robotic camera typically deployed for scientific research or forensic study, Price captured thousands of high-definition images in a single sitting, focusing on a specific area such as the arm or leg,” the plaque informs us. The resulting photos “were subsequently stitched together using satellite-imaging software, run through a 3D graphics program, and adjusted by a fashion retoucher.” The strangeness of Price’s flesh-code hybrids exemplifies a confusion common to our age, when photographs have become malleable and, at the same time, computer-generated images have become hyperrealistic. In his video essay Redistribution (2007–ongoing), Price alludes to part of this effect by discussing the related concept of the “uncanny valley”—that queasy perceptual problem, first identified by roboticists, that makes all-too-real simulations seem, at the same time, eerily unreal—or as the artist puts it, the “point at which the verisimilitude of the human likeness achieves a degree of success that consumers find revolting.”

Seth Price, Occult Cameo 1, 2001. Collage with marker on paper, 12 × 13.125 inches. © Seth Price. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

Considering an even earlier set of works by Price shows how far back his interest in jamming our normal perceptual processes goes. Entitled Occult Cameo 1 & 2 (both 2001), they are a pair of collages with magic marker on paper, each duplicating the same eighteenth-century optical illusion: a face that looks like a bearded Cavalier when seen one way, but like a crowned, leering skull when looked at another. Cognitive scientists refer to this sort of mental flip-flopping as multistable perception. The experience is more powerfully conveyed in Price’s well-known wall pieces that form silhouettes of hands and faces via negative space; many people see works like Marriage Stencil or Untitled Map (both 2008) and think they are merely pseudo-geographic abstractions. The figure seen in Occult Cameo 1 & 2 is also reproduced as a small illustration in Price’s publication Dispersion (2002); though this influential essay has frequently been employed as an all-too-convenient means to interpret his knotty oeuvre as a comment on digital technologies, the appearance of this and other optical illusions in its design has largely gone unremarked upon.

Seth Price, Occult Cameo 2, 2001. Collage with marker on paper, 12 × 13.125 inches. © Seth Price. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

PS1’s wall text also asserts that Danny, Mila, Hannah, Ariana, Bob, Brad shows the connection that Price’s art has to “the body,” a statement that is both obviously true and so broad as to be meaningless. More specifically, Danny et al. can be read as contemplations of the skin as a kind of variable container, circling back to Price’s use of floppy envelope shapes and flexible industrial packaging techniques in earlier sculptures and wall pieces. Moreover, as the deathly grins of his Occult Cameo faces attest, Price has long used visual puzzles such as these to contemplate the void of mortality, to evoke the negative space of nonbeing—an existential focus clearly expressed in so much of Price’s work that relatively few commentators have mentioned it, perhaps displacing anxious thoughts onto the immaterialities of technology.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was recently published by Seven Stories Press.