James Hannaham

James Hannaham

Return of the Mythic Being: the Museum of Modern Art mounts a vast retrospective of the artist’s work.

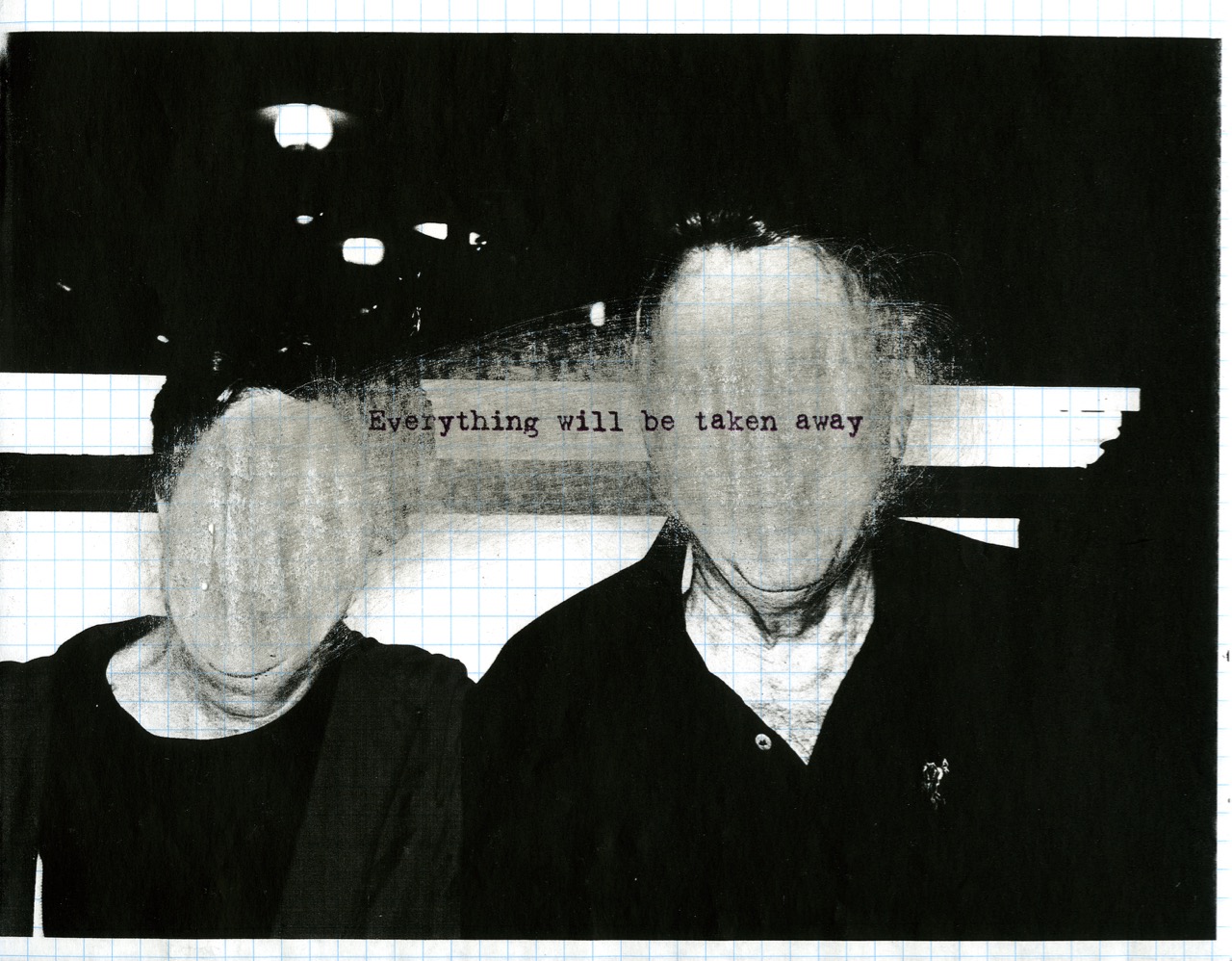

Adrian Piper, Everything #2.8, 2003. Photocopied photograph on graph paper, sanded with sandpaper, overprinted with inkjet text, 8 ½ × 11 inches. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation.

Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016, the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through

July 22, 2018

• • •

After feasting upon the Museum of Modern Art’s gargantuan retrospective of Adrian Piper’s wildly inquisitive, fiercely intellectual, incredibly funny performances, writings, sculptures, drawings, paintings, sound art, interventions, and installations, spanning just over a half-century, you may find that you’ve run out of superlatives. (Did I miss anything? Wait—the exhibition also references her academic work in philosophy. There are films. And she dances.)

Piper gives you all the feels, usually a few per artwork. If you seek catharsis, you’ll find it; if you dig brainy conceptual pieces and minimalism, you will linger among her copious obsessive graph-paper drawings; if it’s levity you crave, her performances elicit uneasy giggles and outright guffaws; if you hanker for the deft skewering of race and gender relations, this is your barbecue; if you prefer art that memorializes the victims of discrimination, get out your hanky; if you like your artists confessional, Piper gets achingly personal; if you want to feel conflicted and skeptical about conceptual art, there are a few pieces for you too. You can get angry with her occasionally (not a bad thing), but you will definitely leave convinced that Piper has always been in synch with or ahead of her times, including now.

Adrian Piper, What It’s Like, What It Is #3, 1991. Video (color, sound), constructed wood environment, 4 monitors, mirrors, and lighting, dimensions variable. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation.

Mounted in the midst of MoMA’s renovation chaos—which my paranoid negritude suspects is no coincidence—one first encounters Piper’s work on the second floor with What It’s Like, What It Is #3 (1991), an installation consisting of a blindingly white room in which stadium seating surrounds a white column. On each side of this obelisk, a video screen projects a loop of four views of the same black man announcing, in a stentorian voice, “I am not stupid, I am not childish, I am not smelly,” and other adjectives—horny, scary, shiftless, servile, etc. This is, of course, the subtext of the many complicated things people of color must say in our defense. Piper forces us to focus on the defiant man instead of his antagonists—my response was visceral shock and despair. By contrast, Imagine [Trayvon Martin] (2013), a picture of the murdered boy’s face behind a red target inviting visitors to empathize with him, including free printed flyers of the image, seemed directed toward people who don’t spend as much time identifying with Trayvon Martin as I do. I guess we need both approaches.

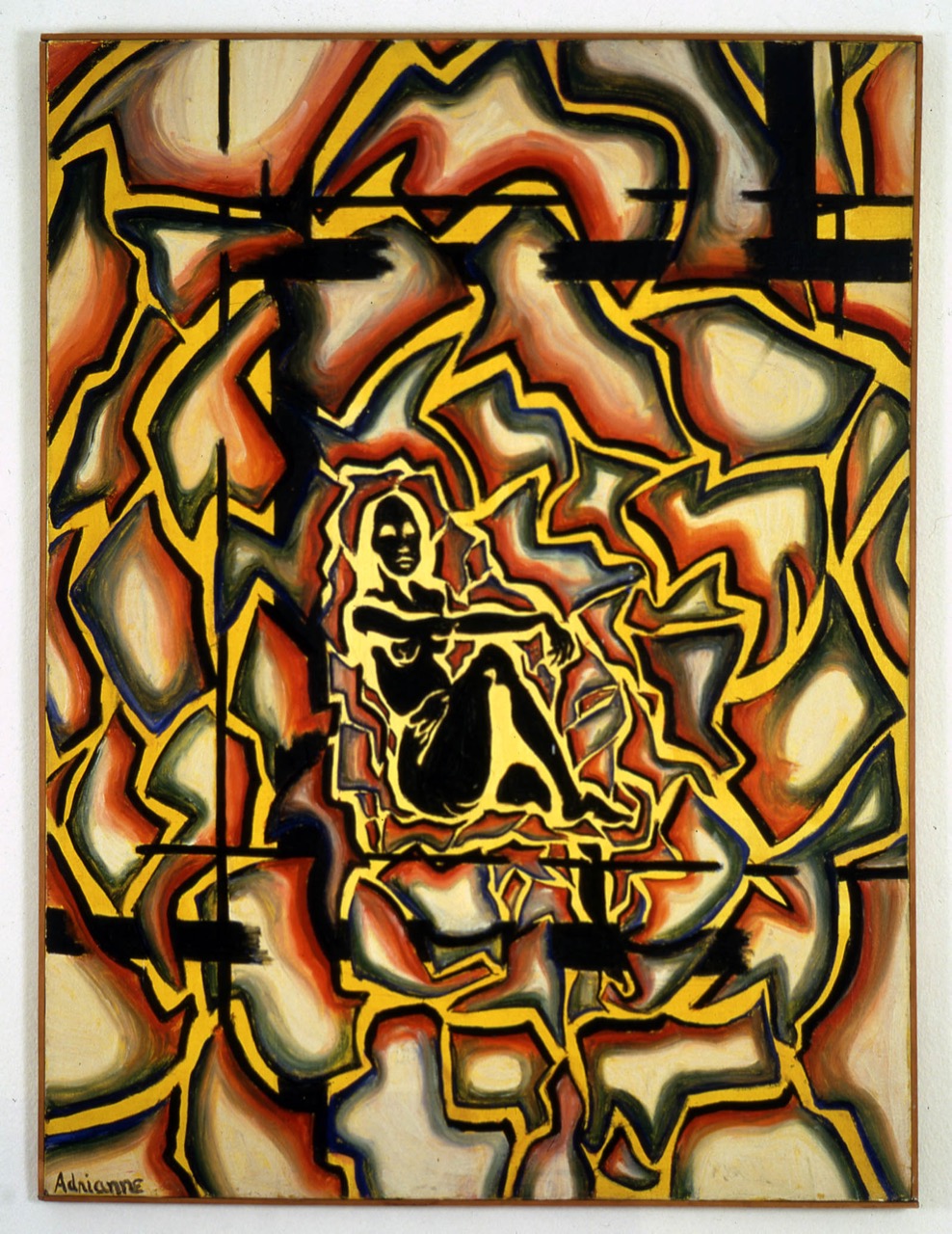

Adrian Piper, LSD Self-Portrait from the Inside Out, 1966. Acrylic on canvas, 40 × 30 inches. Photo: Boris Kirpotin. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation.

The exhibition then leaps to the sixth floor, where over 290 more works await, in a mostly chronological order that illuminates the brilliant shifts in Piper’s oeuvre. If one only knows her later art, it’s an odd surprise to discover the strength of conceptual minimalist Sol LeWitt’s influence in her youth. You witness her pre-LeWitt LSD paintings, made circa age seventeen, which look like cool concert posters inspired by the drug if not created while on it, giving way to geometric forms and a level of meticulousness that seems, at times, halfway to madness. Here and Now (1968) consists of a notebook full of eight- by eight-inch grids of one-inch squares. On each page, Piper has typed a note inside one of the sixty-four squares describing the position of the note itself. The fact that she is a Virgo makes astrology seem real.

It is also extremely pleasurable to watch her later work, more easily readable as political, emerge from these seemingly dispassionate conceptual pieces. Were they political, too? One might retroactively interpret, for example, Infinitely Divisible Floor Construction (1968), made of many brown squares of particle board placed on the floor in a mathematical series, as a mordant statement about race in 1960s America. Which it can’t help but be, just by being brown? A little? And breaking things down? In 1968? Am I crazy? A lot of Piper’s 1960s constructions incriminate the viewer this way, inviting us to read further than seems logical and get caught in their various traps. Piper’s deep attention, combined with her deadpan humor, makes your own brain a little hyperactive, alive to your own thought processes.

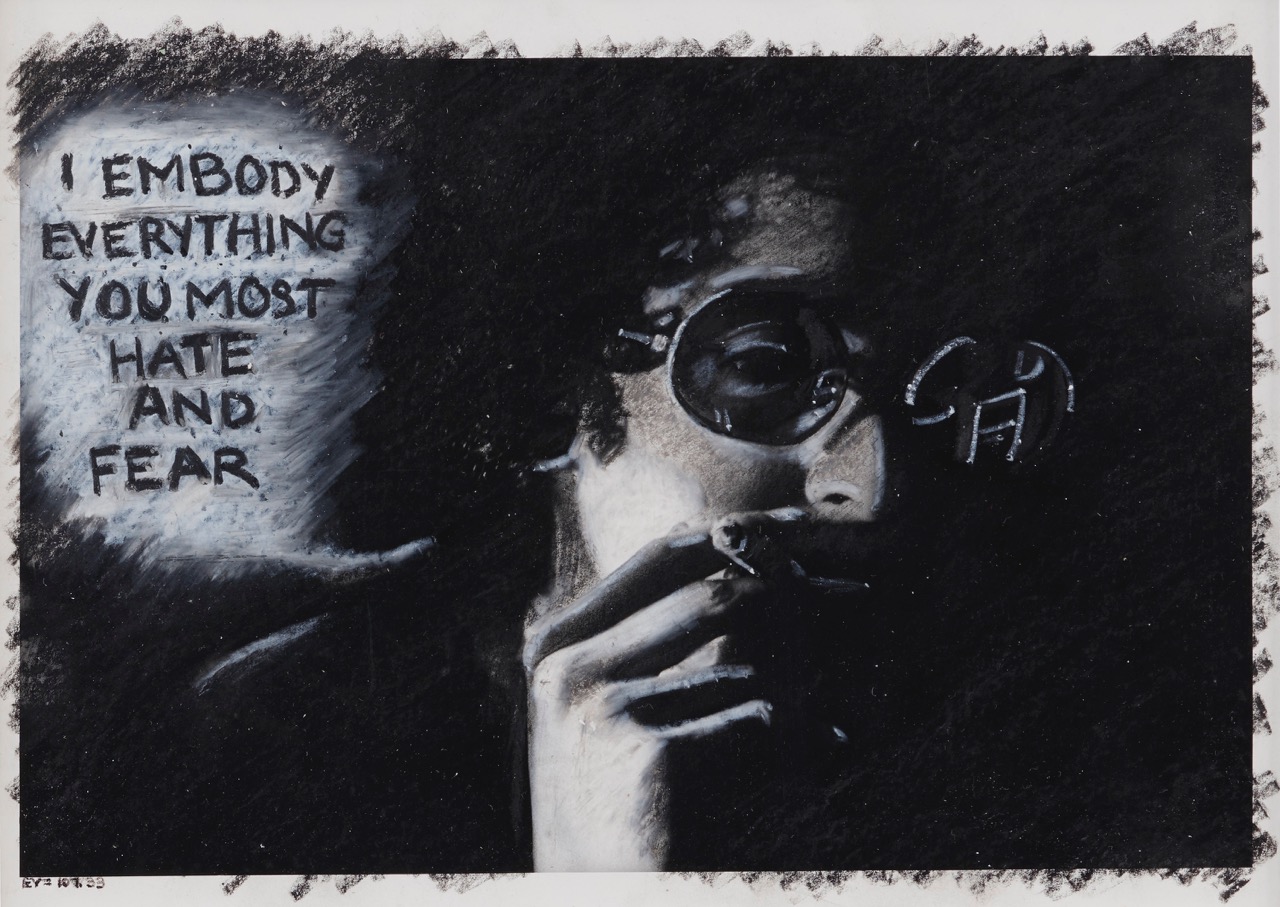

Adrian Piper, The Mythic Being: I Embody Everything You Most Hate and Fear, 1975. Oil crayon on gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation.

In the 1970s, her drawings and constructions, which on the surface may have seemed in keeping with elders like LeWitt or Agnes Martin, and sustained a nearly Albers-level obsession with the square, were actually huge departures that gave way to performances. Her guerilla actions include such loopy events as Catalysis IV (1970), in which Piper stuffs a piece of cloth in her mouth and rides the public bus to the Empire State Building to experience life as a repellent figure; an untitled performance (1970) where she puts on a blindfold and stumbles around Max’s Kansas City; and the sublime Mythic Being series (1973–75), where Piper walks through Harlem dressed as a somewhat ridiculous, definitely ethnic (black-ish? Puerto-something?) male character, and, having memorized a few lines from her diary, repeats them aloud. These actions are shocking or funny on the surface, yet also daring and deeply empathetic. They had massive influence on performance artists to come. The Mythic Being also shows up in many drawings, and a series of ads placed in the Village Voice.

Piper later handed out business cards, a.k.a. My Calling (Card) (1986–90), which today we’d describe as “interventions,” one of them a brown missive that explains Piper’s subject position as a black-identified woman who could pass for white but chooses not to, and also denounces racist statements made in her presence; the other a white card rebuffing anyone who harasses her in public space. “This card is not intended as part of an extended flirtation,” it reads. MoMA has made copies of these perennially handy materials available to the public.

In nearly every one of these works, Piper employs a cheeky sensibility that exposes and ridicules the racism and sexism America holds dear, in a sincere effort to obliterate them.

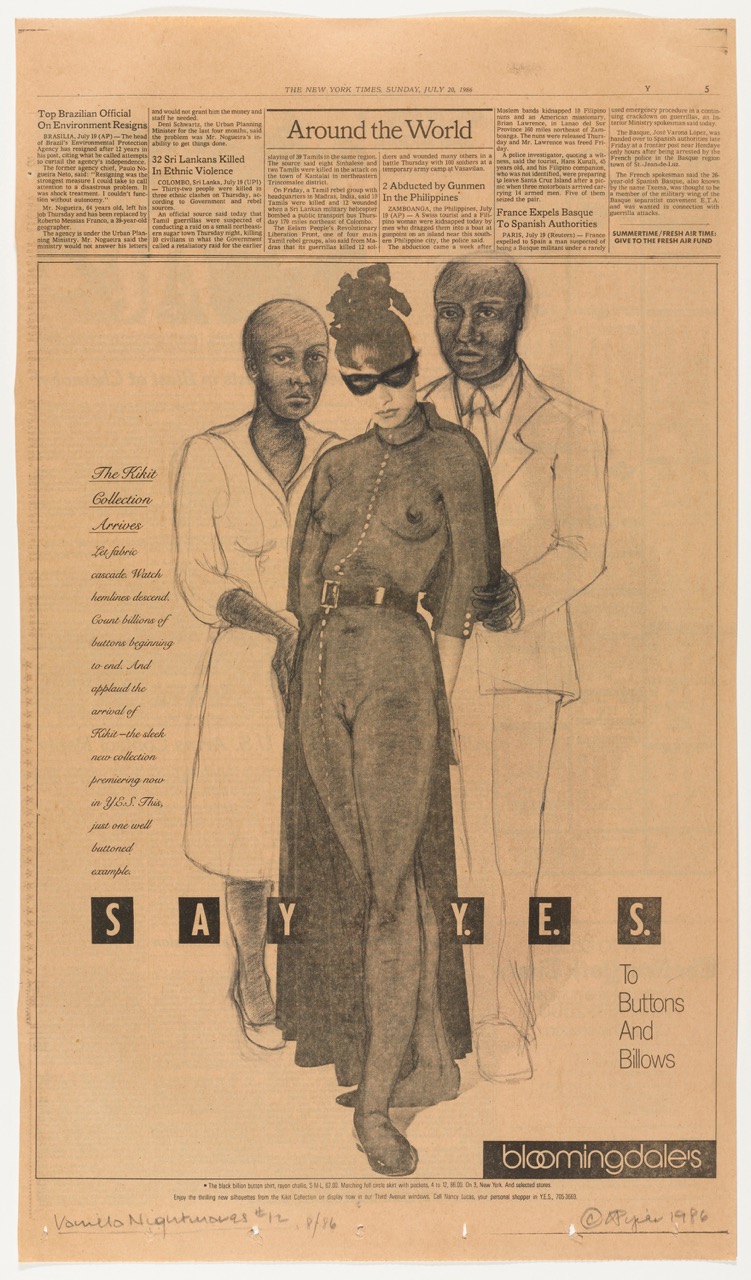

Adrian Piper, Vanilla Nightmares #12, 1986. Charcoal on newspaper, 23 ½ × 13 ½ inches. Photo: John Wronn. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation.

Yet another approach to exposing -isms and -phobias emerges from Vanilla Nightmares (1986–89). Piper appropriates familiar pages from the New York Times and superimposes, intertwines, defaces, and erases them, transforming their banal surfaces into charcoal drawings of black and white people, often involved in sexual activity. The world is watching, reads one headline, referring to South Africa’s racial strife, while below a black figure enters a bald, white, presumably female figure from behind. It is not hard to imagine Kara Walker, then an undergraduate art student (and already a Piper fan), taking note.

I want to write about almost every piece. My highlights (today, at least) include Thwarted Projects, Dashed Hopes, A Moment of Embarrassment (2012), Piper’s resignation from blackness (once irritating, now sorta Kanye-funny), and Black Box/White Box (1992), consisting of two rooms, one painted black, one painted white, containing nearly identical elements: a light box showing Rodney King’s beaten face and audio of his famous attempt at fostering racial harmony after the 1992 LA riots, a photograph of George H. W. Bush shaking hands with the officers acquitted of attacking King, and a box of tissues. What Will Become of Me (1985–ongoing) is an unfinished work that consists of jars containing cuttings of Piper’s hair and nails, and a note pledging that her remains will become part of the piece upon her death. Though I hope this artwork takes a long time to complete, it will be a fitting end to a life that has so often blurred the boundaries between art and existence.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.