James Hannaham

James Hannaham

A show presents little-seen work by a cadre of polyamorous,

post–World War One artists.

The Young and Evil, installation view. Image courtesy David Zwirner.

The Young and Evil, David Zwirner, 533 West Nineteenth Street,

New York City, through April 13, 2019

• • •

The Young and Evil, curated by art critic Jarrett Earnest, fills one wing of the sprawling David Zwirner gallery with a perplexing group of photos, paintings, and sculptures by a tightly knit circle of polymorphously perverse artists who first came together in the 1930s. This clique was incestuous enough to inspire a complicated Mark Lombardi–type diagram in the press materials, connecting the major players by various associations, often sexual ones—photographer George Platt Lynes, a friend of the writer Katherine Anne Porter, had a long three-way love affair with writer Glenway Wescott and his partner, the curator and publisher Monroe Wheeler, while Wescott was linked to controversial painter Paul Cadmus, who had relationships with (among others) painters George Tooker and Jared French.

Jared French, Murder, 1942. Egg tempera on gessoed panel, 16 ⅝ × 14 ¼ inches. Image courtesy Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

French, in turn, married photographer-painter Margaret Hoening, and for a while the two of them formed a collective with Cadmus called PaJaMa (whose work consisted mostly of glamorous black-and-white nudes of the boys frolicking on the beaches of Fire Island and Provincetown). Meanwhile, painter and set designer Pavel Tchelitchew and his partner Charles Henri Ford had friendships with Gertrude Stein and poet Edith Sitwell, the latter of whom had fallen in love with Tchelitchew, and Alfred Kinsey was—oh, you get the idea.

As long as that idea consists of a bewitching whirl of free-wheeling post–World War One white hedonism worthy of The Sun Also Rises. In fact, Hemingway based a character from that novel, Robert Prentiss, an up-and-coming novelist, on Wescott, though Prentiss enters the book only long enough to make a faintly condescending remark to Jake Barnes (“Oh, how charmingly you get angry,” he said. “I wish I had that faculty”). The show cribs its title from a novel too, a very arch, unapologetically profane and homosexual one written by Ford with poet and film critic Parker Tyler.

The Young and Evil, installation view. Image courtesy David Zwirner.

The insular allure and decadence of this crew recalls similar cabals, from the Romantic poets to Warhol superstars to Nan Goldin and friends. Indeed, one purpose of the exhibition seems to be to boost the group’s myth as progenitors of later LGBTQ artists to the same level as similar velvet mafias. But on close inspection, the comparison seems forced. True, many of the works on display include intimate portraits, nude portraits, and sexually explicit drawings and photographs of gay sex. Often the exhibit seems as if the Leslie-Lohman Museum of LGBTQ art has simply moved a little further uptown. But queer content alone does not make you a champion of LGBTQ causes, nor does iconoclastic behavior constitute an artistic legacy, particularly if it was never part of public discourse.

Though the free-love sexuality of the young and evil distinguished their biographies and mordantly appears in aspects of their public work, many of the pieces that compose the show stayed within the collections of this circle of friends. “This art has been literally and figuratively dragged out of closets for this exhibition,” as the press release puts it. The best Lynes photos here, for example, are a trio of high-fashion phallus shots and a double portrait of two men in bed that came from a file Wheeler buried in his personal papers. These erotic images were made by and for complicated, privileged, and closeted white men and the straight women who enabled them. Surely, we can peek into this fascinating world without glorifying it.

Paul Cadmus, Shore Leave, 1933. Tempera and oil on canvas, 32 ×

35 ⅛ inches. © 2019 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society.

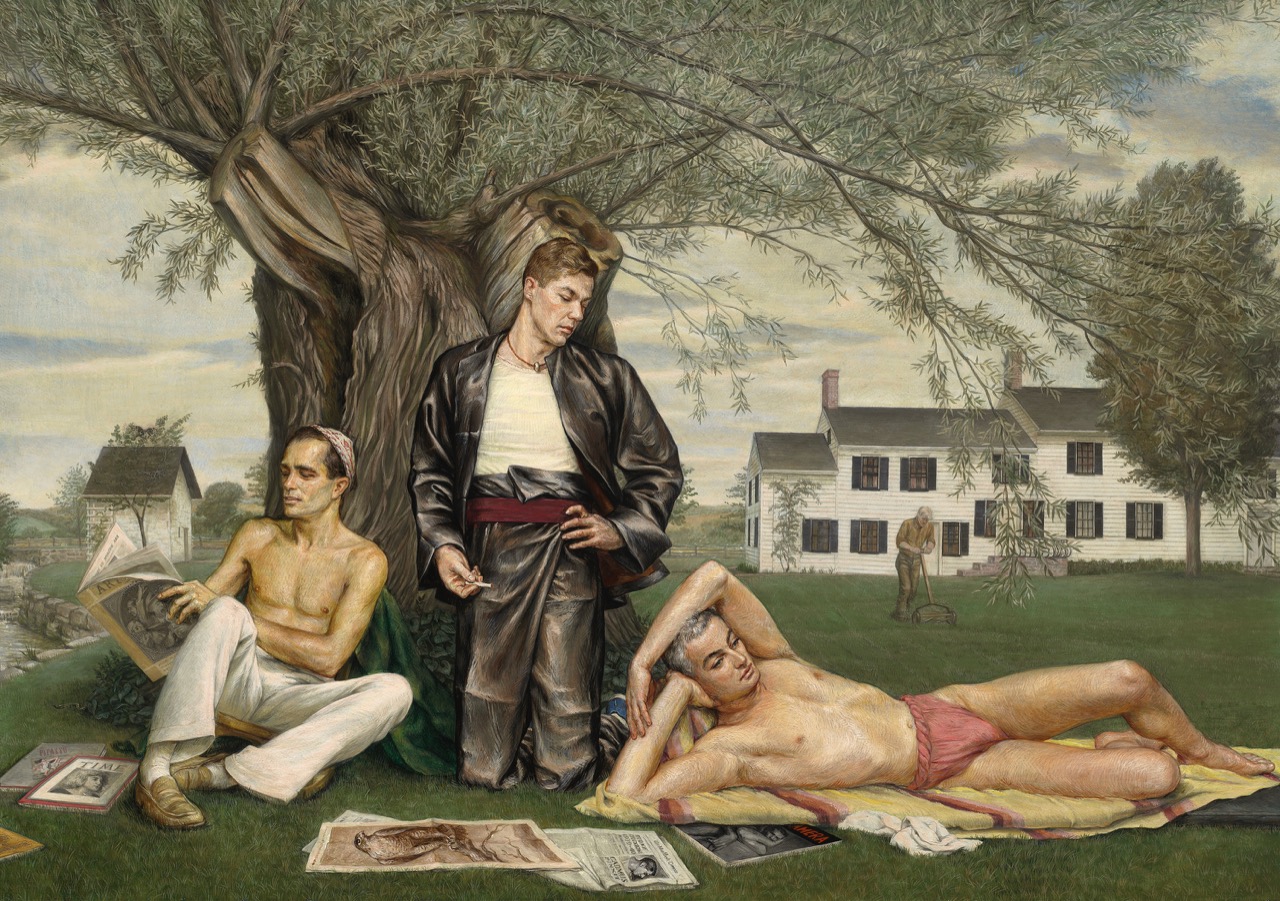

Cadmus has perhaps the highest profile of anyone in the show, and is exemplified here most saliently by Shore Leave (1933), though any regular visitor to the Whitney’s permanent collection has ogled the rounded butts of its drunken sailors on multiple occasions. Other Cadmus works include Stone Blossom: A Conversation Piece (1939–40), a voluptuous depiction of life at Wescott, Wheeler, and Lynes’s country house, a painting many may never have seen, and Herrin Massacre (1940), a classically graphic depiction of the 1922 murder of twenty strike-breakers by union members (sorry, leftists!)—the painting’s anti-union overtones trouble the exhibit’s attempt to position these artists as revolutionaries rather than reactionaries.

Paul Cadmus, Herrin Massacre, 1940. Tempera and oil on panel, 35 ⅛ × 26 ¾ inches. © 2019 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society.

Curator Earnest intends to rescue the group from such potentially damaging perceptions, but in many respects this proves difficult. These bohemians, though they worked from the 1930s through the 1950s and beyond, either rejected or remained relatively unmoved by nearly every major development in avant-garde art happening around them. Europe enchanted them, they infiltrated Gertrude Stein’s world, and . . . meh. Lynes’s photos owe a debt to Man Ray, but most of these artists held fast to the more fabulous, less psychological elements of American realism—the stylized figure, representation, advertising. They seemed charmed by surrealist images, which first hit American shores in the early 1930s, but ignored the surrealist processes (exquisite corpse drawings, automatic writing, etc.) that arrived with figures like André Breton during World War II. They also refused to update their artistic materials and even turned to outmoded ones, like egg tempera and silverpoint.

Paul Cadmus, Stone Blossom: A Conversation Piece, 1939–40. Oil and tempera on linen on panel, 23 ½ × 33 ½ inches. © 2019 Estate of Paul Cadmus / Artists Rights Society.

As a result, their most direct descendants remain commercial illustrators. The full thighs and haunches of Cadmus’s figures provide the link between Thomas Hart Benton and Tom of Finland; Tooker and French seem to have gone to the future and come back with Rush album covers.

The Russian-born Tchelitchew, however, one of the few artists here who didn’t grow up in the tristate area, pushes his work into darker, more emphatically surrealist territory than the others. His contributions include a Dalíesque portrait of Fidelma Cadmus, Paul’s sister, Portrait of Fidelma (ca. 1947), which seems to depict only the veins and arteries in her face, giving the painting an eerie spaghetti-monster aura; a related series of see-through heads from the late 1940s; and a disturbing painting called The Sun (1945), an image that resembles a giant veiny eyeball and takes up the whole frame of the painting. But these late works also testify to his rejection of the constructivism of his former teachers in prerevolution Kiev.

The Young and Evil, installation view. Image courtesy David Zwirner. Pictured, left to right: Pavel Tchelitchew, Portrait of Fidelma (ca. 1947), The Sun (1945), and The Lion Boy (1936–37).

While we can admire the daring content of the work these artists left to us, as well as their pioneering polyamory, it’s regretful that the art they made about the lives they lived wasn’t more widely seen at the time—by the standards of our twenty-first century exhibitionist society, they were firmly closeted. But we must remember that at the time homosexuality was criminalized, and the stakes for coming out in the United States, even among a community of artists, far greater than today. The chance they took was to put the truth of their lives into a time capsule and hope for the best. In 1930s America, it was nearly impossible to be both a homo and a hero.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.