Nico Israel

Nico Israel

The Jewish Museum engages Walter Benjamin’s magnum opus in an exhibition filled with profane illuminations.

The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, installation view. Photo: Will Ragozzino / SocialShutterbug.com.

The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, the Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through August 6, 2017

• • •

“I need not say anything. Merely show.” So wrote Walter Benjamin in one of several notes addressing the “Theory of Knowledge” that would guide Das Passagen-Werk, his never-completed study of the iron-and-glass-covered shopping arcades in Paris—the city Benjamin viewed, for its nascent consumer culture, as “the capital of the nineteenth century.” “The rags, the refuse,” Benjamin continued, “these I will . . . allow . . . to come into their own: by making use of them.” The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, curated by Jewish Museum director Jens Hoffmann, “makes use” of Benjamin’s ideas in a similar way, drawing on the rag-like fragments of writing posthumously gathered into his magnum opus, and organizing an art exhibition around them. In fact, the crowded but exhilarating exhibition both shows and says quite a lot—about contemporary art’s contemporaneity, its relation to commodification and critical theory, and its political potential.

Several concepts of Benjamin’s long ago entered the vocabulary of art theory and criticism, through the writings of Rosalind Krauss and Benjamin Buchloh, among others, and have become such frequently encountered reference points on curators’ wall texts as to verge on the platitudinous: art’s “loss of aura,” its relation to “technical reproducibility,” objects juxtaposed to form a “constellation” with the viewer as “flâneur,” etc., etc. Happily, Hoffmann avoids this tendency to regurgitate received Benjaminian wisdom, opting instead to turn toward some of the melancholy Berliner’s less-picked-over material. By basing the exhibition on the Passagen-Werk’s “convolutes” (notes gathered to form quasi-chapters), and bringing together compelling works by familiar and lesser-known artists of the past twenty years, he makes a case for Benjamin’s—and recent art’s—importance and vitality.

The exhibition—like the Parisian arcades themselves, as Benjamin understood them—creates a productive tension between structured (the necessity to walk through) and unstructured experience (the possibility of stopping, paying close attention, and doubling back). The convolutes (lettered A through Z and then with a few small letters from a to r) are presented out of alphabetical order, and yet their subject matter often collides with that of a nearby convolute, as when “Convolute Z: The Doll, The Automaton” (Markus Schinwald’s Untitled [Machine I], 2016) is juxtaposed with “Convolute B: Fashion” (Collier Schorr’s Jennifer [Head], 2002–14).

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #474, 2008. Chromogenic print, 90.8 × 60 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

At times, the art’s connection to its rubric feels a bit mechanical. Under “Convolute H: The Collector,” for example, Hoffmann presents Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #474 (2008), an image of herself as a bejeweled late-middle-aged art collector, with hideous penciled-in eyebrows and perfectly manicured nails, pictured in front of a wall of presumably collected portraits. Under “Convolute O: Prostitution, Gambling” appears Good Hand Bad Hand (2010), Rodney Graham’s photographic lightbox diptych of a stone-faced casino gambler with a Make America Great-style trucker hat and sunglasses; one hand is possibly a winning one, the other a losing one. Under “Convolute g: The Stock Exchange, Economic History,” Andreas Gursky’s Singapur Börse I (1997) offers a frozen, bird’s-eye view of the swirl of activity on Singapore’s stock exchange. In each of these three cases, however, the on-the-nose illustrative dimension of the photographic works is counteracted by the sheer excellence of the photographs themselves and by how, consciously or not, their makers engage questions of lasting import raised by Benjamin’s writing: the relation between collecting and the desire to arrest the passage of time; between gambling, political risk, and destiny; between capitalism of the past and capitalism of the (then-)present.

Rodney Graham, Good Hand Bad Hand, 2010. Two painted aluminum lightboxes with transmounted chromogenic transparencies, 35.3 × 29.3 × 7 inches each. Image courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery. Photo: Ken Adlard.

The show works best when the connections between the convolute title and the art are a bit more, well, convoluted: under “Convolute I: The Interior, The Trace,” Hoffmann presents Simon Evans’s The Voice, an Eva Hesse-like sculptural “drawing” made from mixed media on paper that gives the sense of an emanation from an obscure interior. Whether or not he intends to, Evans engages the questions of language-as-such and gesture, persistent concerns of Benjamin’s. (Evans’s is one of a very small handful of quasi-abstract artworks in the show.) Under the rubric “Convolute Q, Panorama,” Nicholas Buffon creates roughly two-foot high models of iconic downtown Manhattan restaurants and bars (the Stonewall Inn, complete with flag announcing it as a National Historic Monument; Odessa Restaurant; Katz’s Delicatessen), places that carried different collective histories for generations of New Yorkers. (The functioning Russ & Daughters restaurant in the basement of the museum is historically simulacral in its own right, though perhaps lacks the tenderness conveyed by Buffon’s smaller-scale models.)

Nicholas Buffon, left to right: The Stonewall Inn, 2017; Katz’s Delicatessen, 2017; Odessa, 2016; Lower East Side Coffee Shop, 2016. Foam, glue, paper, paint. Courtesy the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts. Photo: Will Ragozzino / SocialShutterbug.com.

Given Benjamin’s enormous intellectual debt to Marx, Freud, Proust, Kafka, Adorno, Scholem, and other, mostly atheistically inclined, thinkers of Jewish heritage, this venue seems an especially apt one at which to stage a Benjamin exhibition—even if the “Jewish” (or messianic/redemptive) dimensions of his thought are largely left unexplored. Kenneth Goldsmith, founding editor of UbuWeb, has created a “poem” for each convolute’s wall text, composed in signature “Kenny G”-fashion of appropriated fragments of existing texts, from Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow to lyrics from the Cure. Goldsmith has been pursuing his quote-and-recontextualize shtick for over thirty years to occasional take-the-bait outrage, most recently in his book Capital: New York, Capital of the 20th Century, with its titular riff on both Marx’s study of political economy and Benjamin’s essay on Baudelaire.

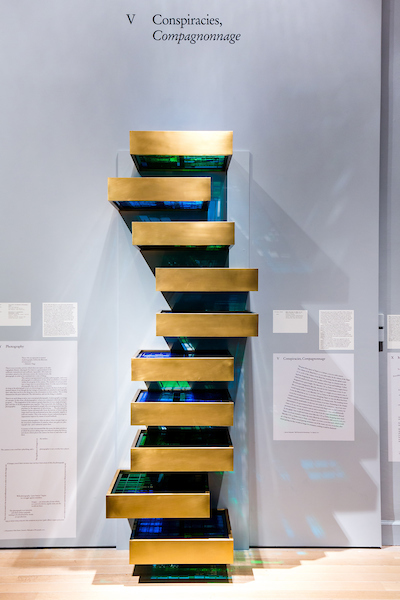

Voluspa Jarpa, What You See Is What It Is, 2013. Steel modules, laser-cut acrylic plates, 116.5 × 24 × 43.4 inches. Courtesy Mor Charpentier, Enrique Jocelyn Holt Collection, and the artist. Photo: Will Ragozzino / SocialShutterbug.com.

Benjamin, of course, wrote about the potential for appropriated elements to be ignited when brought into in new contexts, with the capacity to create what he called an “image” or “profane illumination.” In stark contrast with Goldsmith’s flat-affect experiments, Chilean Voluspa Jarpa’s citation/replication of Donald Judd’s iconic minimalist stacked boxes in What You See Is What It Is (2013) are far more in tune with Benjaminian ethics. For her installation under “Convolute V: Conspiracies, Compagnonnage,” Jarpa has placed into the rectangular prisms brightly colored sheets of plastic that reproduce declassified US government intelligence documents concerning its involvement in twelve Latin American countries during the Cold War, with so many redactions that the plastic sheets are full of holes and look like large, colored data punch cards. The effect is to transform Judd’s boxes into drawers of file cabinets with secret information that in their obscure, cipher-like way bear witness to the arrest of popular will and the murder of nameless thousands. (“The construction of history,” wrote Benjamin, “is consecrated to the memory of the nameless.”)

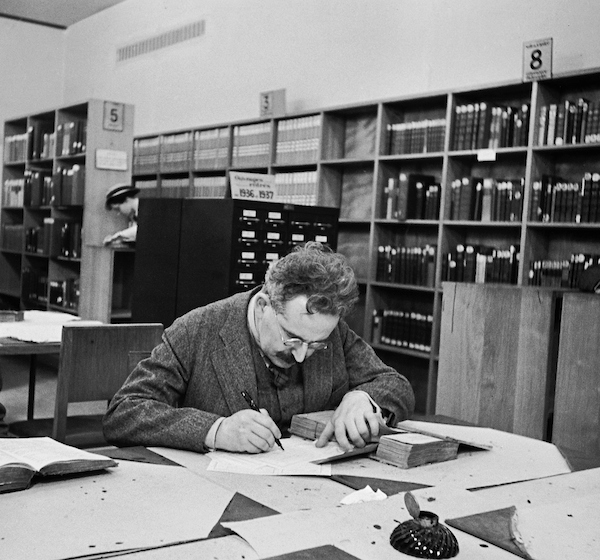

Gisèle Freund, Walter Benjamin at the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, 1937. Image courtesy IMEC, Fonds MCC, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York.

That the Passagen-Werk was never completed owed in large part to Benjamin’s predicament, by 1938, as a stateless man, after the Third Reich stripped German Jews of their citizenship. On the run from Nazi and Nazi-sympathizing authorities for several months in 1940, he committed suicide at the French-Spanish border when a Kafkaesque, Franco-era bureaucrat told him that despite his valid travel visa to the US, he would not be allowed to pass into Spain, whence he hoped to disembark to the US. While this exhibition was almost certainly conceived in a period when such mass deportations seemed a distant memory, the works it presents, and the Benjaminian thought it engages, are more than timely. As Benjamin himself asserted, “the past can be seized only as an image that flashes up at the moment of its recognizability.”

Nico Israel, a professor of English at the CUNY Graduate Center and Hunter College, is the author of two books, Outlandish: Writing between Exile and Diaspora (Stanford, 2000) and Spirals: The Whirled Image in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (Columbia, 2015). He has published numerous articles on modernist and contemporary literature and literary theory and over seventy-five essays on contemporary visual art, many of them for Artforum.