Sowon Kwon

Sowon Kwon

The artist’s new show plays with the visual power of words.

Kay Rosen, Angered and Deranged, 2017. Acryla gouache on watercolor paper, 22.75 × 30.50 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © 2018 Kay Rosen / Artists Rights Society.

Kay Rosen: Stirring Wirds, Alexander Gray Associates, 510 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through April 7, 2018

• • •

During a recent subway ride, I found myself surrounded by sans serif type: on the slogan on a fellow rider’s canvas tote; on the travel destination poster just behind her; on the horizontal ad banners for a local college, a new toothpaste, the state’s plan for paid family leave. Sometimes condensed, often in all caps, and always bold, those fonts bore more than a passing resemblance to the ones Kay Rosen has used throughout her decades-long career. This observation about blocky, rectilinear type and its ubiquity in urban life is perhaps unremarkable, but it is coincident with the realization that the text-based artists most often cited alongside Rosen—Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Lawrence Weiner, Bruce Nauman, Ed Ruscha—also tend to favor such fonts, signaling arguably, and for some ironically, a kind of conceptualist “style.”

But what distinguishes Rosen’s use of “generic” typefaces is that without compromising their hard-edged, formal rigor her work never feels cold, didactic, or accusatory, as in a critique from above, nor does it traffic in pseudo-profundities, or retreat back to pictorial illusion. A word that comes to mind is homegrown, as in mined from and distilled through the bustle and din of the vernacular. Which is not to suggest a folksy lack of sophistication. Far from it. Rosen’s paintings, drawings, and large-scale public works are as taut and nuanced as they are familiar and funny (and they are funny). With color, scale, and the simplest of modifications to found words, Rosen reveals pointed and revelatory messages in everyday “linguistic events.” Her new exhibition Stirring Wirds finds Rosen true to form, responding with characteristic concision and wit to our political moment, to the continued legacies of colonialism and social injustice, and to presidential administrations past and present.

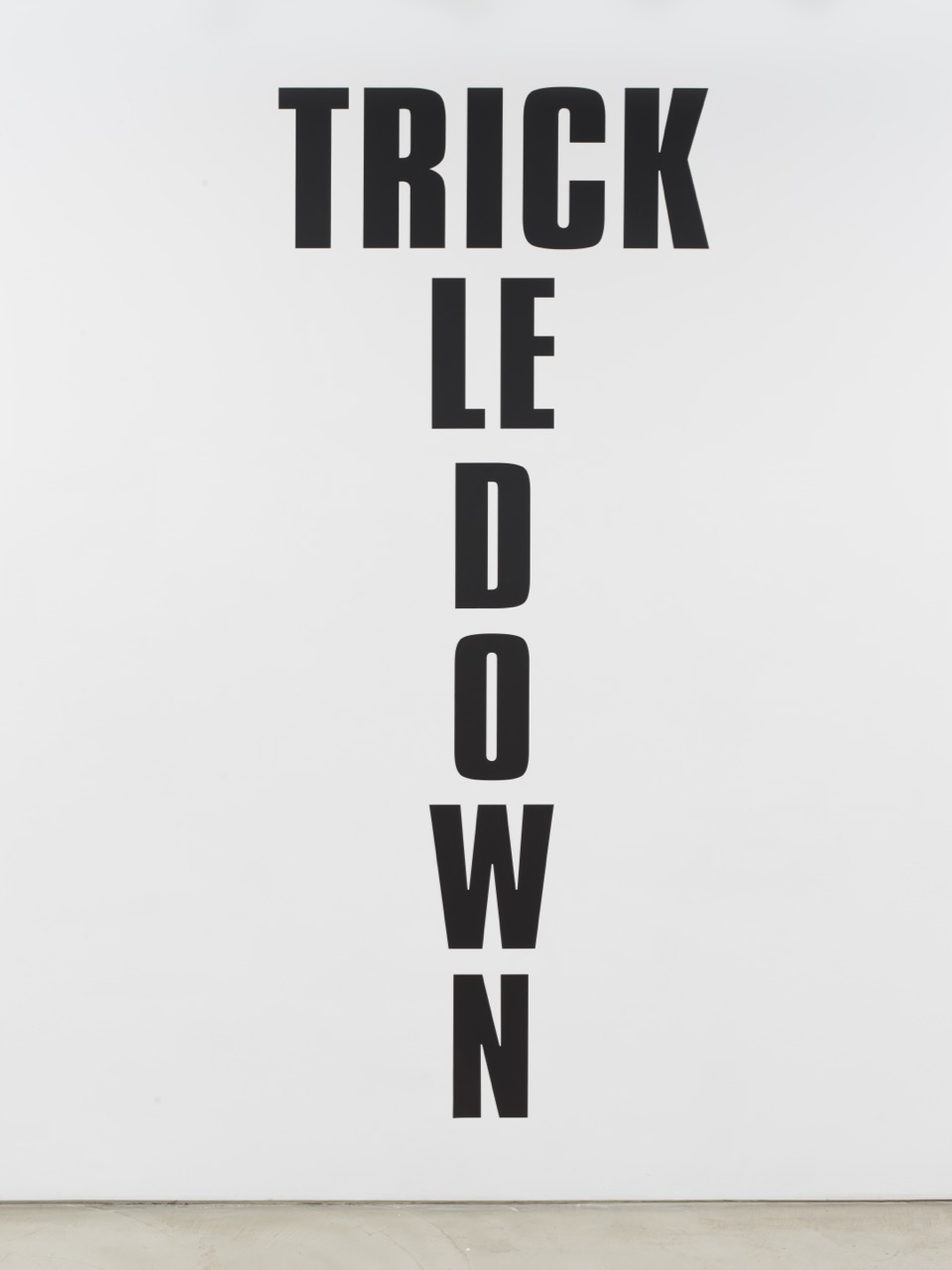

Kay Rosen, Trickle Down, 2016/2018. Paint on wall, dimensions variable; horizontal letters are 16.25 inches high, vertical letters are 15 inches high. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © 2018 Kay Rosen / Artists Rights Society.

Consider Trickle Down (2016/2018)—a nearly nine-feet-high T-shaped configuration of black letters that is one of the two murals on display, in which D-O-W-N spelled vertically, is holding up T-R-I-C-K, centered across. (The passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and its derivation in Reaganomics may resonate for some here.) The leftover L and E sit together in between the two words, like a capital in classic post and lintel construction, stabilizing the structure and composition. The margins and kerning for L-E are tight, such that their overall width is not greater than the widest single letter W below, and as if they are hemmed in and prevented from rolling over to the next, or any other line. Hence, that which is left over does not get redistributed below. Trickle Down might appear at first to perform the action it describes, but any suggestion of movement downward is an illusion, and the illusion holds up the trick.

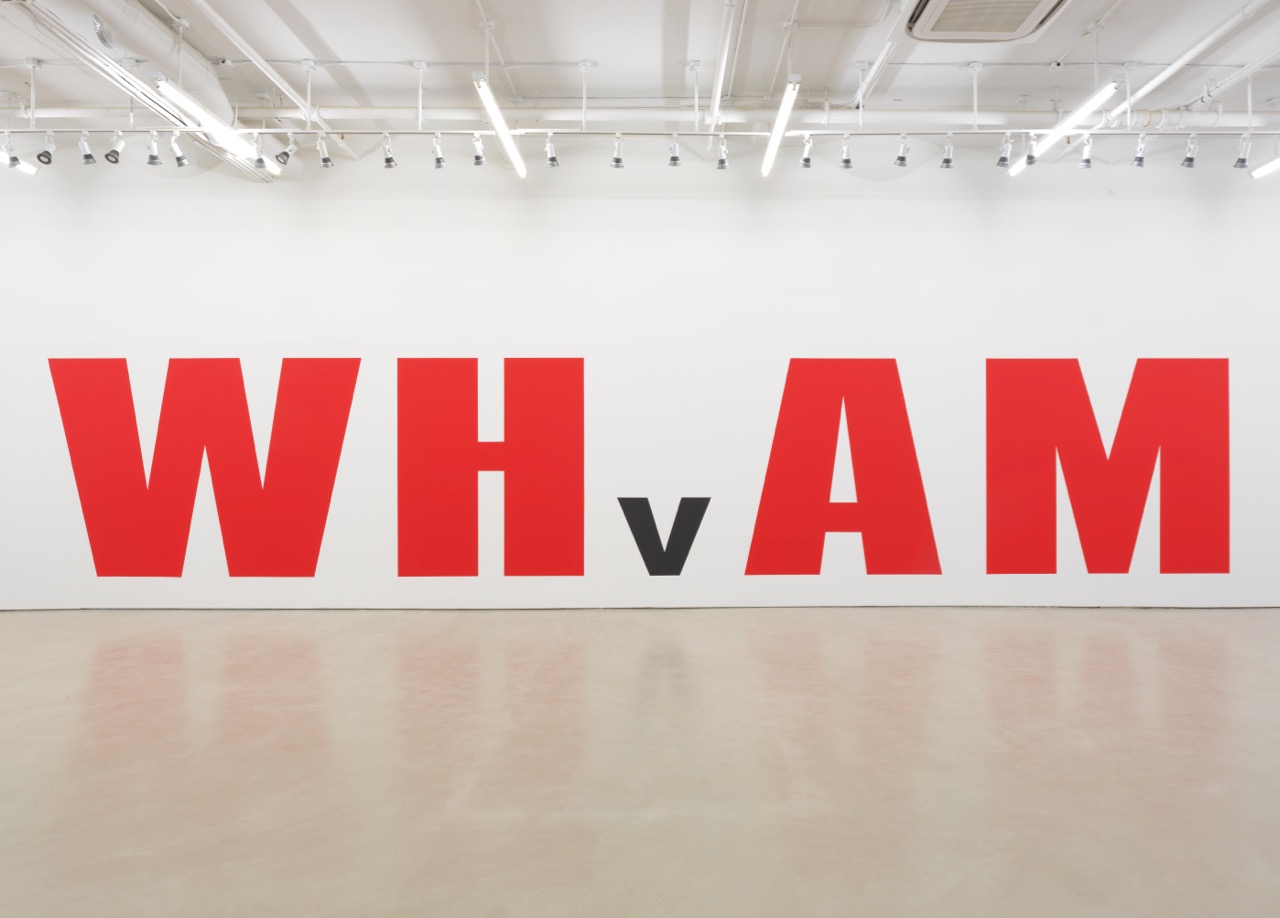

Kay Rosen, White House v. America, 2018. Paint on wall, dimensions variable; red letters are 78.75 inches high. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © 2018 Kay Rosen / Artists Rights Society.

White House v. America (2018), the other wall painting in the exhibition, is composed of the letters W-H-A-M rendered in vibrant cardinal red. Dividing them into pairs and pointing down like an arrow, a smaller, black “v” is a reminder of Trickle Down’s color and directionality, but the piece is decidedly horizontal in orientation. Commanding a forty-two-foot-long span of a fifty-foot wall, WHvAM impacts our perceptual field at almost every turn in the space.

While Rosen’s work invites many associations (from George Michael’s pop band to Russian suprematist color schemes), the letters are also clearly an abbreviation, marking our current political moment metaphorically as one of competition or battle. The “v” additionally suggests litigation and legality, as in Roe v. Wade, where stakes are high, and getting ever higher. Indeed, AM is the first-person conjugation of the verb, “to be,” and as nuclear taunts escalate, it is not inconceivable that the threat from the executive branch of government could be fundamentally existential.

The onomatopoeic WHAM, with its efficiency in being both a forceful blow and the sound of such a blow, must also be intentional. And its vigorous and commanding visualization here feels energizing and ultimately empowering, not bleak or fearful. It would have us emboldened and fit like athletes in a grueling sports match, with the drive to strike, to smash, to win against the opposition.

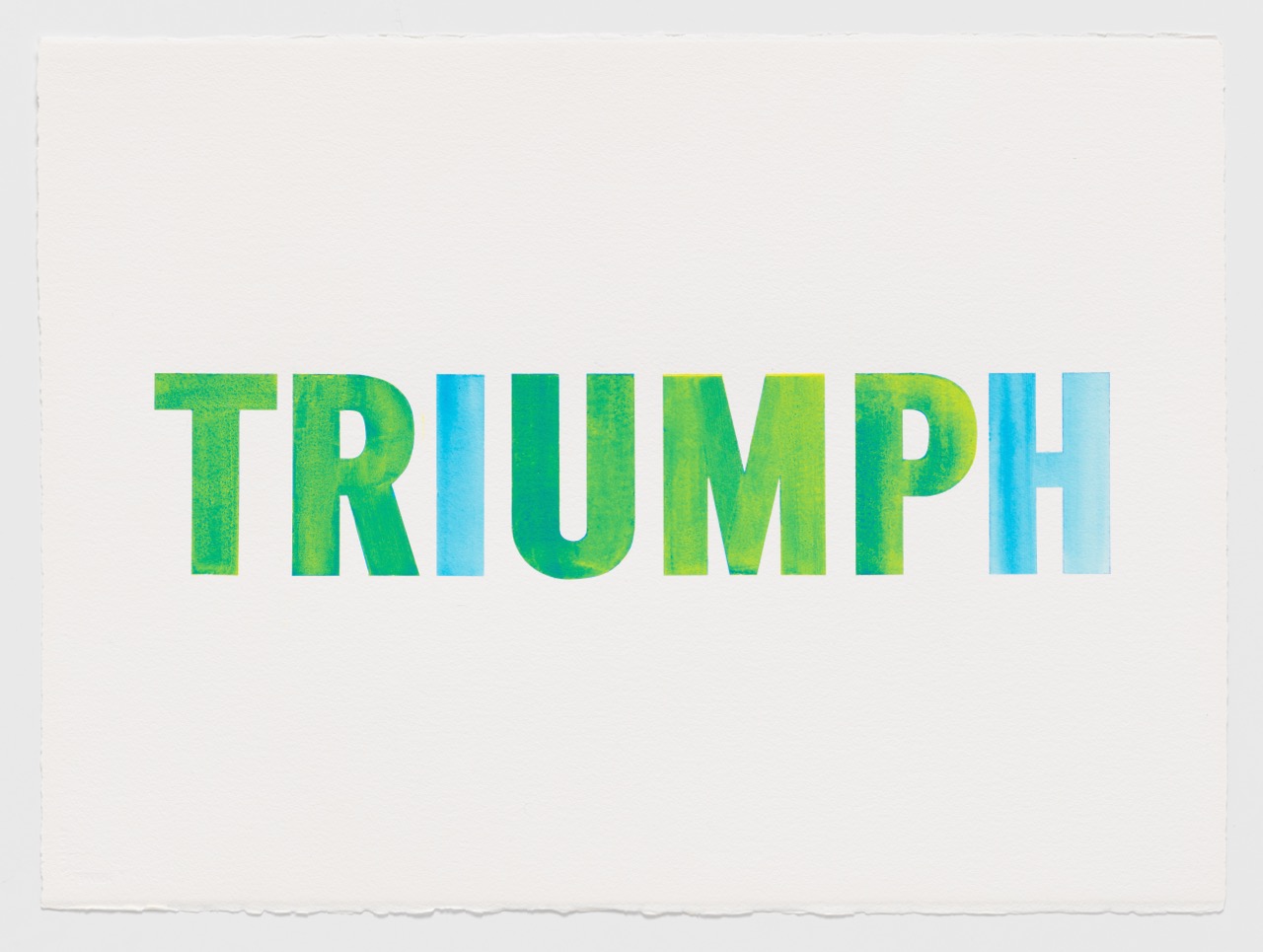

Kay Rosen, Triumph Over Trump (Blue Over Yellow), 2017. Acryla gouache on watercolor paper, 22.50 × 30.50 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © 2018 Kay Rosen / Artists Rights Society.

Rosen trains her sights on the White House’s current occupant in Triumph Over Trump (Blue Over Yellow) (2017). The slippage between Trump/Triumph might seem ambiguous at first glance. I can imagine the canniness of Donald J.’s grandfather Friedrich Drumpf, as much as the passions of those on the WH side of versus, in actively courting the association. But look again carefully and see that T-R-I-U-M-P-H in translucent blue is applied over T-R-U-M-P in yellow. The superimposition is literal and thorough, yielding triumph in an optimistic spring green. Is trumping Trump (and tricks for that matter) only wishful thinking? Can we be scared, sad, and hopeful at the same time? Only if, as WHvAM’s looming presence suggests, we see red both peripherally and head on.

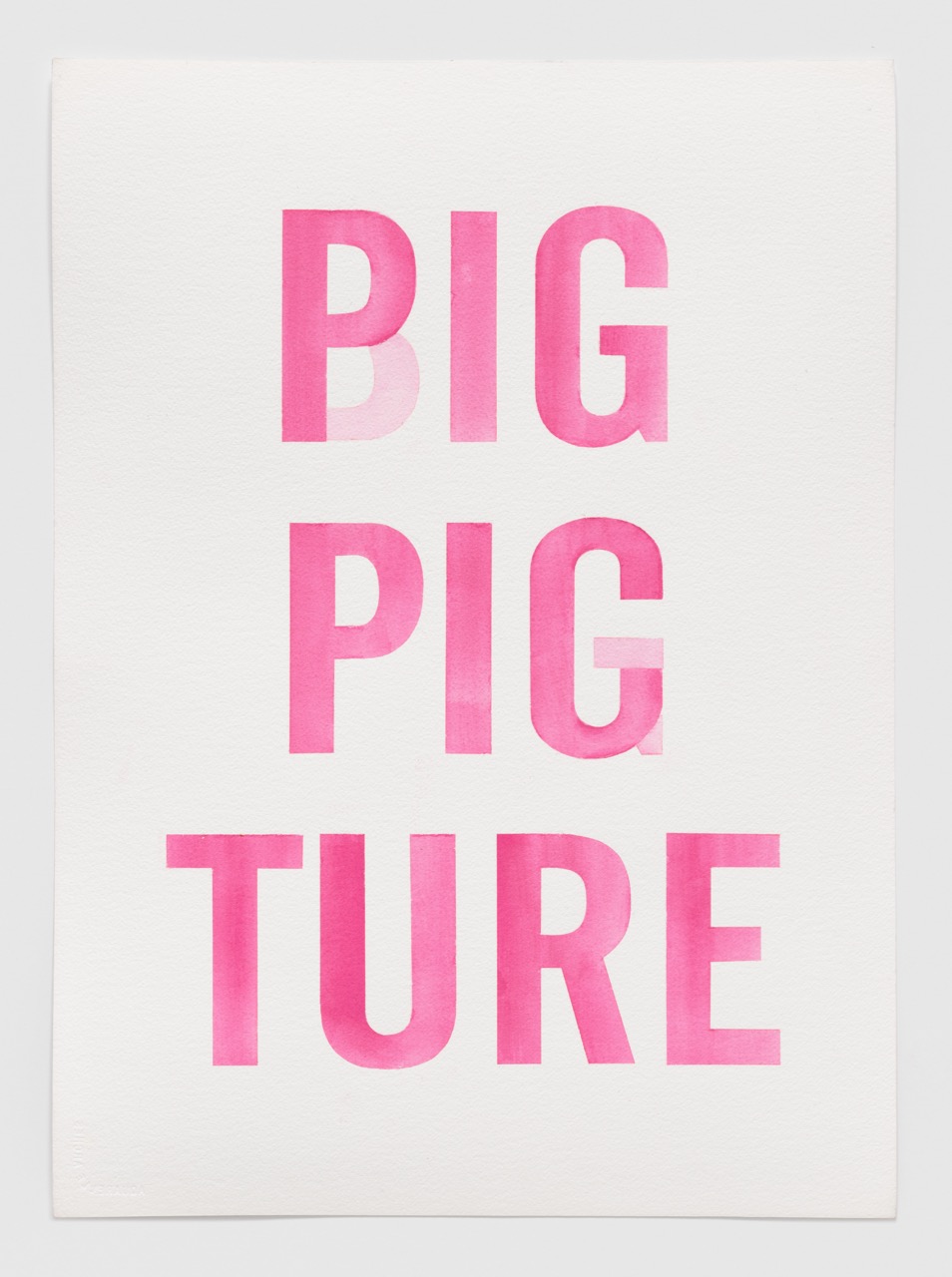

Kay Rosen, The Big Pig Pigture, 2017. Acryla gouache on watercolor paper, 22 × 16 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © 2018 Kay Rosen / Artists Rights Society.

While some works on view resound as if through a megaphone, others are subdued, featuring word play with a subtler visual punch. The show both alerts with urgency and offers moments of quiet reflection and even solace. (We can be several things at once, it seems to assure us.) The Big Pig Pigture (2017), for example, is rendered in thin layers of pink gouache on toothy watercolor paper, with translucent letter shapes overlaid onto each other that suggest variable meanings, and an oscillation between mental and visual registers. These looser, washier effects signal something of a departure from earlier works, which though handmade, can appear as dense and opaque as sign paintings with meticulously uniform brushstrokes. The lighter hand and the suggestion of painterly pleasure had me pause, connecting the physicality of making with the physicality of reading and viewing.

The orthographically anomalous wirds stirring in the title of the show still puzzles me. But it operates similarly, making me stop, to actively look and think more carefully (less linearly than associatively) about its pronunciation and its shape. It looks like “birds” to start, which takes me to the wry and poetic monotypes of Edgar Heap of Birds, another text-based artist seldom acknowledged alongside the conceptually stylish. And then it takes me to the dictionary, which notes that it can be a verb, as in “to express.” As I try to decipher it, I will think about quoting Rosen to a favorite student. She once wrote of her hope for her work to be like language itself, “a vessel . . . for the benefit of the user to be filled up with meaning.” I can almost hear my student’s bass-toned approval and his soothing way of stretching out the monosyllabic. Wirrrd, he would say, nodding in agreement.

Sowon Kwon is an artist based in New York City. Her recent work has been featured at Full Haus gallery in Los Angeles, The Poetry Project, Triple Canopy magazine and Broodthaers Society of America. She also teaches in the Graduate Fine Arts Program at Parsons The New School.