Reinaldo Laddaga

Reinaldo Laddaga

“BOB is not there for you”: a capricious AI creature commands the artist’s new video installation.

Ian Cheng: BOB, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

Ian Cheng: BOB, Gladstone Gallery, 530 West Twenty-First Street,

New York City, through March 23, 2019

• • •

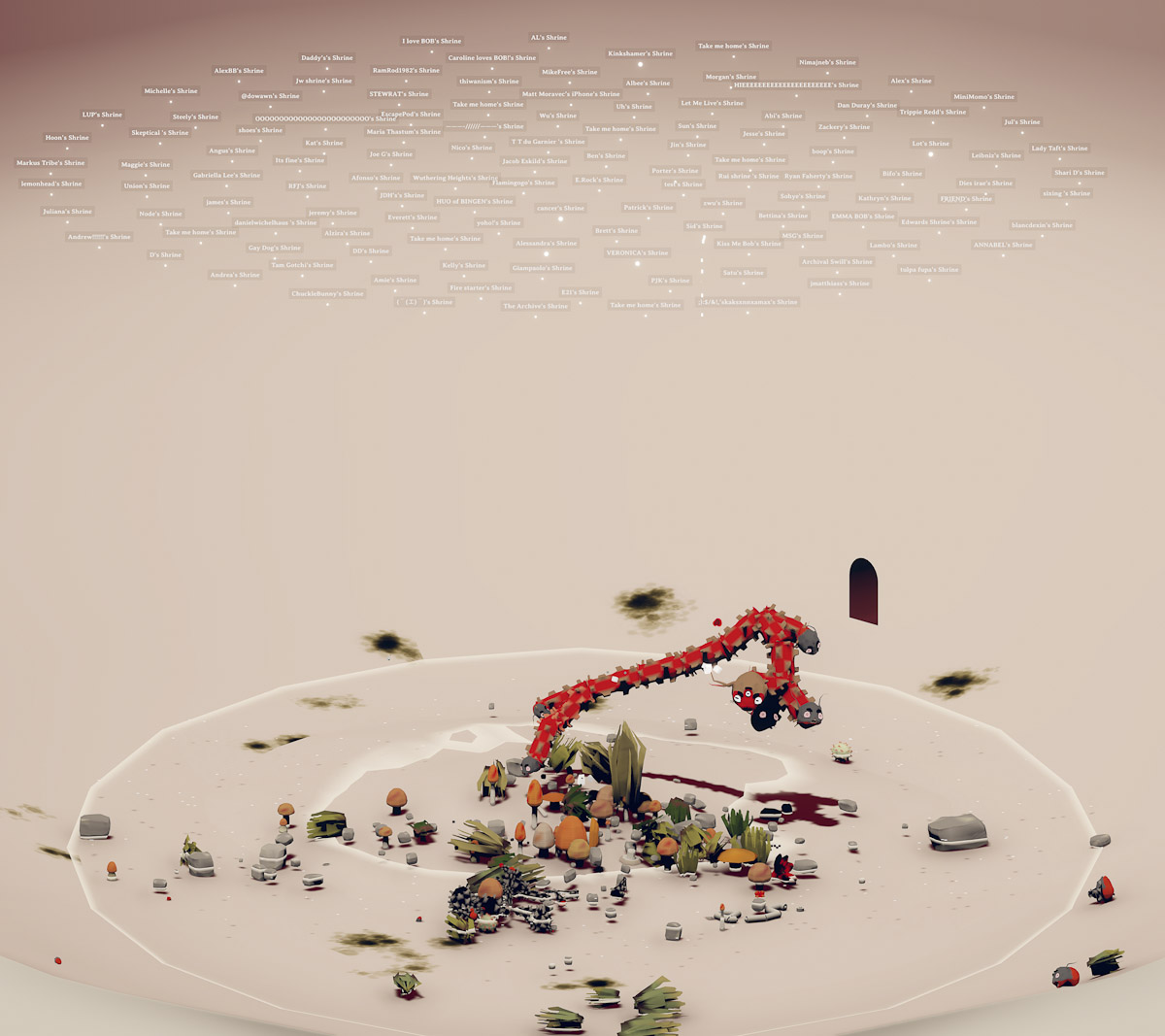

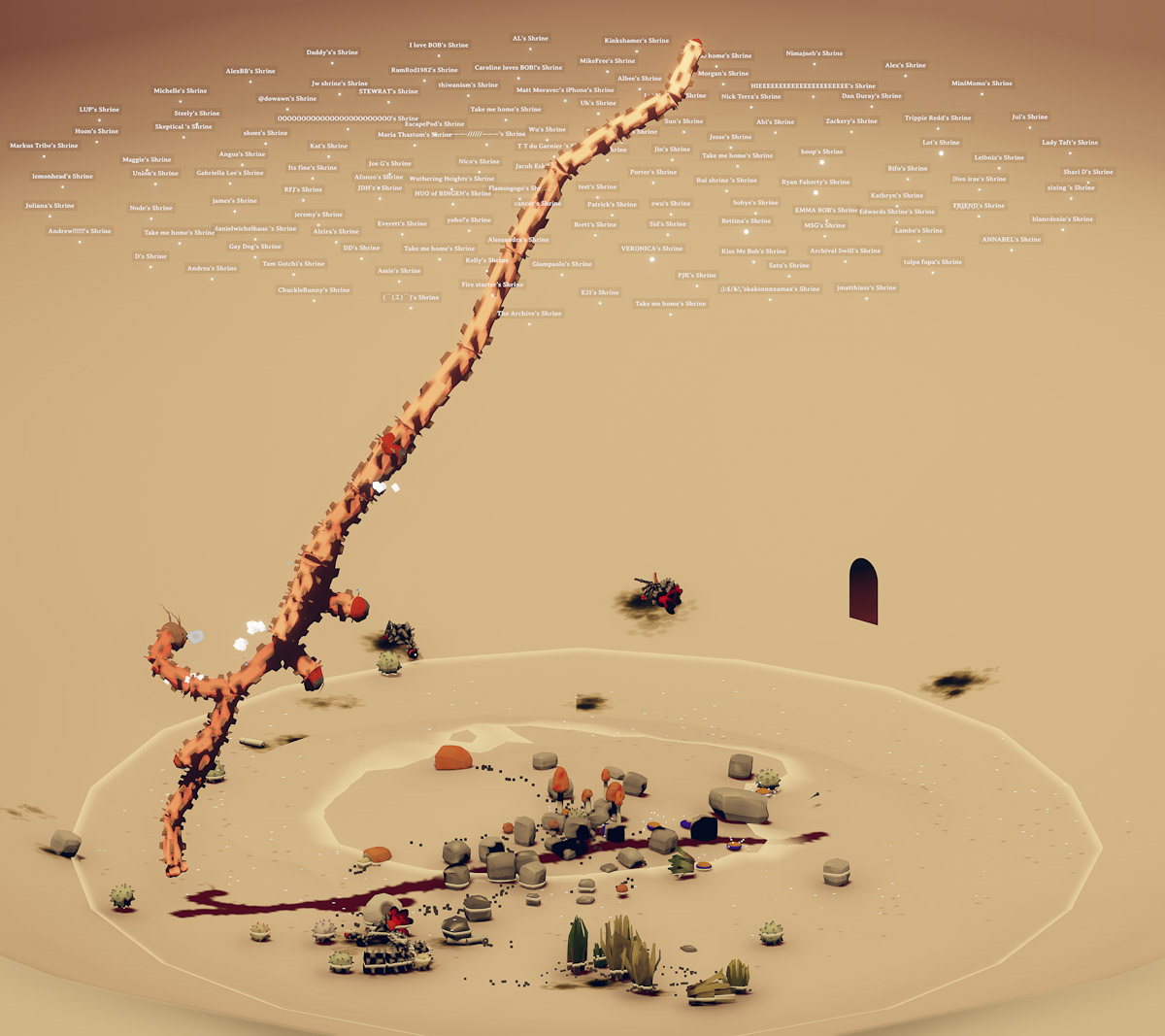

New Yorkers last saw the work of Ian Cheng at MoMA PS1 in 2017, when the LA-born artist presented Emissaries—a trilogy of what he describes as “live simulations.” The principal component of this enormously ambitious project was a sequence of large-scale videos showing landscapes populated by more-or-less human, animal, and hybrid characters who related to one another in enigmatic ways. The profiles of the characters and the parameters of their engagements were predefined, but the system itself was created to engender unpredictable mutations. Cheng’s intention in Emissaries was to compose an artwork that had some of the open-endedness of natural ecosystems. His exploration of synthetic life continues—on a less expansive scale—in a new show at Gladstone Gallery. Here, a twelve-foot-high grid of screens shows an indefinitely evolving video of a digital creature named BOB as it moves in its “sanctuary,” a pinkish-white environment that resembles a cross between an East Asian scroll painting and a zoological habitat.

BOB (an acronym for the phrase “bags of beliefs”) is a reddish-brown snakelike entity with an insectoid head and a shifting number of sentient limbs that continuously contract and expand (BOB’s “flock of Bobbles”). Vast portions of its time are spent ingesting and excreting things in the sanctuary, but BOB is equally prone to seemingly capricious behaviors. If we are curious enough to consult the gallery’s hand-out press release, we learn that the creature’s actions are determined by a “congress of motivating demons.” “BOB’s AI brain is composed of multiple ‘demons’ who compete for control of BOB’s body at any given moment,” Cheng explained to me in an email. “Each demon is motivated to make progress toward fulfilling a mini-story.” Demons are the seats of compulsive desires that have been programmed into the artificial intelligence of BOB to impel it, depending on their momentary combination or conflict, to play, forage, curl, or jump.

Ian Cheng: BOB, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

BOB also reacts to us, thanks to the offerings we make via an iOS app associated with the piece. If we download the application, as I did, it won’t take us long to realize we can use it to post virtual shrines into which we can put a variable number and combination of starfish, shrubs, mushrooms, rocks, and idiosyncratic objects called Spinyfruits, BlackOrbs, and ProximityBombs. We also see the name of our shrine appear in the upper part of the sanctuary, where a cloud composed of the names of all the shrines that viewers have posted is perpetually floating. We present our gifts, but it’s up to BOB to accept them, which it does by suddenly taking a fast, upward leap. When it touches one of the names, a gong sounds and an oval portal opens as the contents of a shrine pour across the screen. I promptly offered BOB a few starfish. I expected to see them fall and anticipated seeing my name in a constantly updating roll call that keeps unfolding on the right side of the screen and mirrors BOB’s Twitter account, where it publishes its actions and the offerings received. But nothing happened, and after a few minutes I was awkwardly left with two different emotions elbowing each other for my attention.

Ian Cheng, BOB, 2018 (still). Artificial lifeform, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The first was the aesthetic pleasure induced by the peculiar beauty of BOB’s dance, the red arabesques it traces on the off-white walls of its residence, its frantic or gentle popping and bobbing, its sudden jumps and languid stances. The elegance of some movements contrasts with the clumsiness of others, as the technical sophistication of the artifact contrasts with the deliberate childishness of the visual design. At times BOB seemed to me like a digital version of those elongated dolls made of fabric that we give our dogs to grab and shake as if they were a dying bird or a squirrel; like those toys, BOB often looks battered and hurt. I found myself hoping that it would find solace in the music emanating from the sanctuary: a carefully designed sonic atmosphere in which swishes and splashes, knocks and clicks, drones and bangs form a weave that is strangely soothing.

Ian Cheng, BOB, 2018 (still). Artificial lifeform, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

But I also noticed a peculiar anxiety that intensified as I kept using the application. This emotion was familiar: it often occurs when I present my offerings on Facebook, that other artificial lifeform that endlessly ingests our data and turns it into a source of its own growth. On those days, I sit at my desk to wait for droves of cartoonish thumbs and schematic hearts to fill my own sanctuary and get restless if they don’t, or if the responses are too few. I feel unchosen. The same subtle distress reappeared at Gladstone. When I first sent gifts to BOB, my attitude was condescending—as it tends to be when I’m asked to interact with an artwork. I expected the portal with my name to immediately open and let my starfish rain on the poor creature. But it didn’t happen, and I started to worry. I posted increasingly desperate offerings and wondered if I had inadvertently done something inappropriate. But then I remembered Cheng’s words in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist: “BOB is there not as a pet for you or as a kind of character for your enjoyment, you are there for BOB to consume or reject you as a viewer. Maybe BOB looks to you to escape its own boredom. But, if you bore BOB, BOB will go off and carry on with its own life. BOB is not there for you.”

Ian Cheng: BOB, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

At the entrance of the room where BOB currently resides, a white-on-black design inspired by Tibetan thangka paintings schematizes its life cycle. The image, together with the mention of sanctuaries, offerings, and shrines, contributes to the curiously religious atmosphere of the show. Gladstone Gallery is the place where a conflicted childlike creature is waiting to receive gifts provided by us, its doting parents, but it’s also the temple where a moody deity resides. The icons of traditional religion are not placed in consecrated buildings to be on display; they are the vehicles of a transcendent gaze. In front of them, we are called to prostrate in a gesture of obedience. Similarly, for a moment, BOB induced me to adopt the pose of the supplicant. It wasn’t hard, given how well I have been able to train myself through endless interactions in digital space. I left the gallery. At night, at home, I opened the application. I received a notification: BOB had accepted my offerings. I was relieved. I imagined my starfish silently falling on the platform where the creature moved, ominous, beautiful, puerile.

Reinaldo Laddaga is an Argentinian writer based in New York. The author of numerous books of criticism and creative nonfiction, he taught for many years in the Romance Language Department of the University of Pennsylvania. He has just completed two manuscripts: a study of Andy Warhol’s practices of fashioning and The Men from Russia (a novel).