Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

Cosmic consequences come for all in Mathias Énard’s diaristic pastiche.

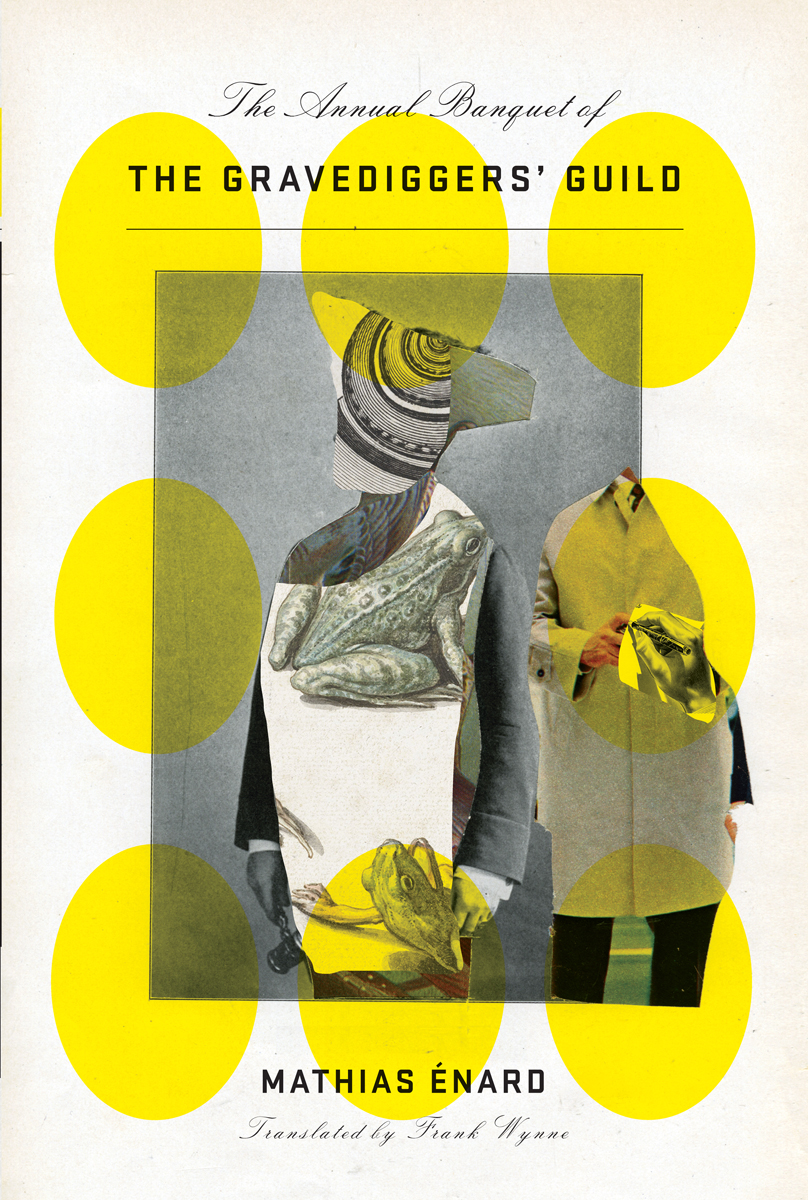

The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild, by Mathias Énard, translated by Frank Wynne, New Directions, 419 pages, $19.95

• • •

“In order for ethnology to live, its object must die; by dying, the object takes its revenge for being ‘discovered’ and with its death defies the science that wants to grasp it,” Jean Baudrillard writes in Simulacra and Simulation. What if we took him at his word? In The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild, by the French writer Mathias Énard (translated by Frank Wynne), ethnology is the pretext for a boondocks metaphysics in which birth and death are endless loops. Boondocks here means the marshlands of western France, where the novel is set, and metaphysics means the Wheel, the narrative device that reincarnates characters across centuries—not always as humans. In Énard’s multiverse, the dead return as wild hogs, fungi, and even a bedbug fattening on Napoleon’s blood.

The book begins as the diary of David Mazon, a bumbling anthropology student who has just arrived in the provinces to spend a year documenting life in “the ass end of nowhere.” Instead, he passes his days in a funk of Tetris, listless masturbation on webcam with his Parisian girlfriend (“I wonder what Walter Benjamin would have thought about cybersex?”), crusades against the worms infesting his bathroom, and general, pompous aimlessness. One by one he meets the locals. It’s an earthy ensemble that includes the village mayor (who doubles as the undertaker), an artist who photographs his own feces, and a seductive farmworker who lives with her dilapidated grandfather and a cousin with an encyclopedic, albeit flawed, recall of historical dates.

A quaint outpost, right? “I hate this shithole,” Mazon declares barely more than a week into his fieldwork. The model for his contempt is Polish anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, whose frank (and frankly lecherous) A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term scandalized readers when it appeared posthumously in 1967. Like Mazon’s journal, Malinowski’s is a spigot of narcissism and bitchery—in his case, toothaches, headaches, hangovers, tropical fevers, bourgeois malaise, and typical European hauteur. “I’m as isolated as Malinowski . . . since isolation simply means not being able to have what you want when you want it,” Mazon writes. No matter that Malinowski was stationed on the Trobriand Islands, deep in the South Pacific, while Mazon is just over a three-hour jaunt from Paris.

From the beginning, then, the novel performs its artifice. A fictional diary that is an homage to a real-life diary, written by a character whose professional objectivity frequently dissolves into comic vanity or self-pity, laced with intertextual allusions, littered with errant brand names always chaperoned by a trademark symbol, strewn with comic-book exclamations like yuck and aaaargh—all of this lays the groundwork for a telescopic, occasionally plodding narrative that departs realism for the shaggy pastures of stylized self-consciousness and pastiche. “The trees are wreathed in a glittering canopy of hoarfrost (a nice turn of phrase, I think),” Mazon notes at one point, enacting his awareness of himself as a narrator and demonstrating the extent to which his diary is not the kind of coiffed, middlebrow literature in which “glittering canopy of hoarfrost” can appear without irony. Mazon nicknames his lodgings “the Savage Mind,” a reference to Claude Lévi-Strauss that all but guarantees a rendezvous with Wikipedia. Allow me to refresh us, courtesy of Patrick Wilcken, Lévi-Strauss’s biographer: “[The savage mind]—free-flowing thought—was a kind of cognitive bricolage that strived for both intellectual and aesthetic satisfaction. It was a very French idea, which brought together the artist and the atelier, the artisan and the dying crafts of a more creative age . . . ”

Bricolage is Énard’s method. Mazon’s diary abruptly ends some eighty-ish pages in, giving way to picaresque chapters about village life that contain speeches, scripts, diagrams of card games, partially redacted ditties, excerpts from Seneca’s letters to Lucilius, Biblical quotes, lists, stem-winder sentences, and other formal hijinks. Six brief interludes titled “Song” are interspersed throughout. These primarily narrate climactic scenes of death or betrayal in different eras, featuring people we don’t meet again—unless, unbeknownst to us ignorant mortal readers, they’re reincarnated as other characters downstream. (Énard frequently, but not always, tracks his characters’ posthumous encores.) A clue as to why these enigmatic episodes are “songs” comes via the village priest, who is dead by the time Mazon arrives but whose life and afterlife haunt the novel. (He’s the hapless soul reincarnated as a wild hog.) We’re told that he listens for the “deep bass song of the divine” in nature, and that melody—however muffled or dissonant or bootlegged—is the backbeat to the book’s cosmology. There is a capricious divinity at work here, and his name is Énard.

The eponymous banquet is the book’s raucous—if sometimes tedious—centerpiece. A three-day bacchanal during which death goes on hiatus, the banquet is when the gravediggers convene to gorge, booze, and debate the finer points of the burial industry. It’s a Rabelaisian spoof; attendees argue about whether women should be admitted to the “Brotherhood” of gravediggers and whether eco-funerals are an ethical imperative. There are rituals and monologues. There’s a singsong tale about the giant Gargantua, who floods an unlucky town with his orgasm: “O how he beat his meat, how he swung his salami! Like the bell ringer of old Notre-Dame, ding dong, ding dong, up down, polishing the snake whose lone eye was blinking.” (The gravediggers “wanted no talk of cum while they ate.”) The pleasures of this section are rather like a banquet itself: myriad but overrich. Elsewhere in the novel, the humor is subtler, more professorial. Catherine de Medici, the ruthless queen of France, is reincarnated as a moth that incinerates itself on a lantern in the courtyard of the Louvre. She’s immediately reborn as a larva, and the karmic corkscrew resumes.

This notion of cosmic comeuppance—the comfort of a rational world, in other words—is related to a strain of reactionary nostalgia in which several characters indulge. The village mayor tells Mazon that he’s in favor of forcing immigrants to adopt French customs. “Our whole way of life could collapse, you know, the social security system, education, these things are fragile,” he says, sounding like the kind of jittery yokel who has lately become an avatar for the body politic. (The only immigrants in the village are a handful of British retirees.) Sometimes, this retrograde spirit is made even more explicit. About several of the village men, Énard writes, “all had grown up to be what their parents had been: farmers, bartenders, butchers and even undertakers.” Gary, one of the locals whom Mazon befriends, “knew that his way of life, the one he shared with his parents, was dying out; that time was permanently changing customs and the countryside.” Insert here Wilcken’s quote about the Savage Mind: “. . . the dying crafts of a more creative age.”

All of this ingrown traditionalism sets up the novel’s final section, in which Mazon’s diary resumes where it left off some three hundred pages earlier. He’s decided to quit his former life in Paris and root himself in the country “to save the planet.” But saving the planet, like living forever, is a fool’s errand. After all, Énard imagines that life in the twenty-second century will be marked by the desolation and decimation of the “Great Drought.” Still, rest assured, the Wheel will roll on, recycling our footloose souls, creating a palimpsest of people and places eternal in its verities. What always remains is what always was: disease, war, famine. But also love, faith, and the kindness of strangers. “No one ever dies instantly,” Énard writes, and no one, neither queen nor moth, dies forever.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.