Blair McClendon

Blair McClendon

In a 1991 essay film about the assassinated Congolese independence leader, Raoul Peck explores the slipperiness of history and the archive.

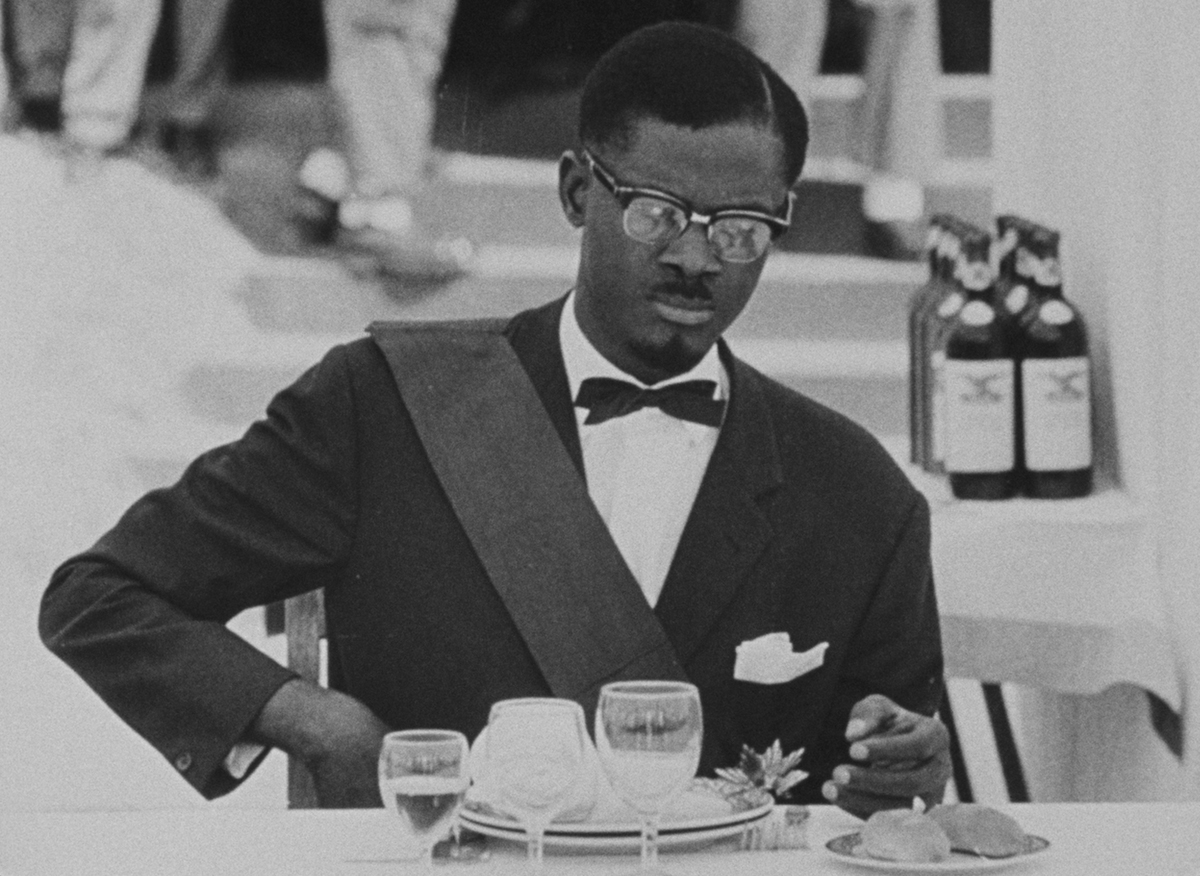

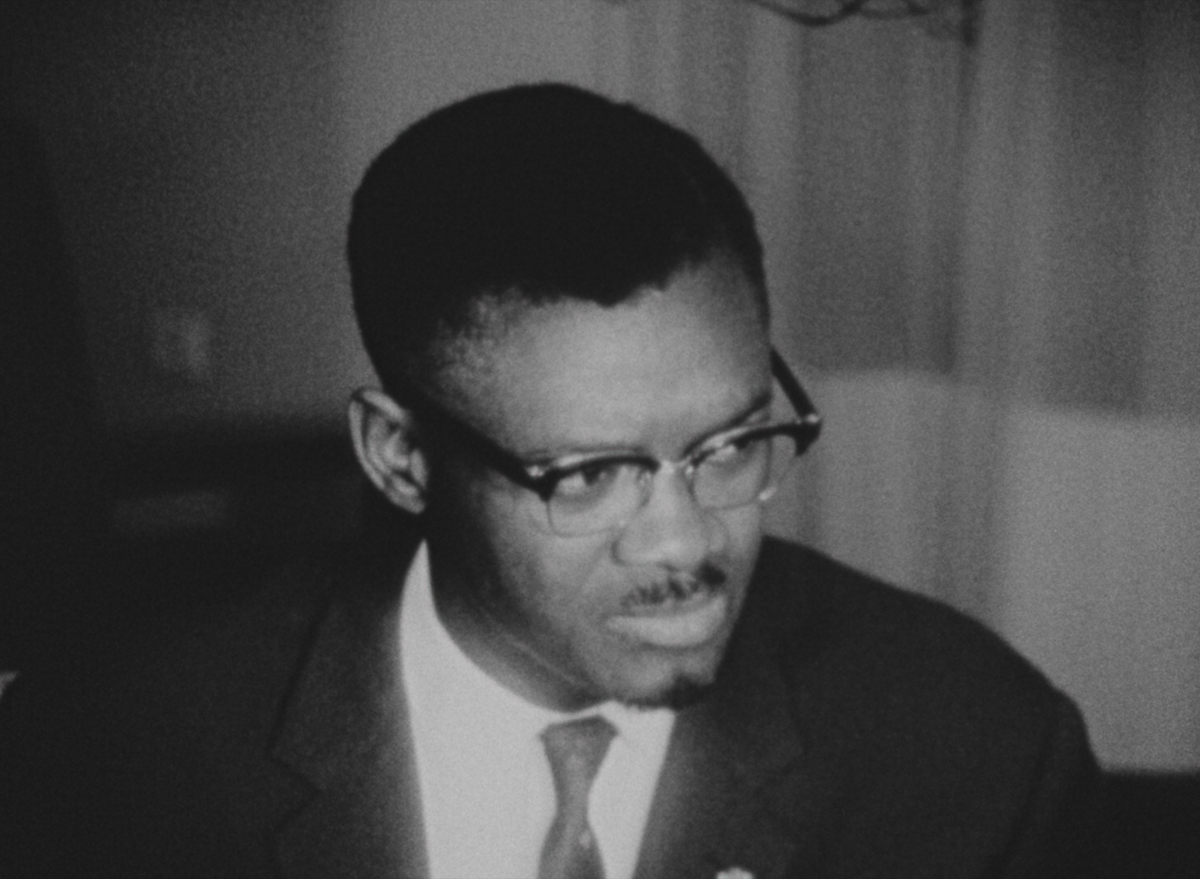

Patrice Lumumba in Lumumba: Death of a Prophet. Courtesy Janus Films.

Lumumba: Death of a Prophet, directed by Raoul Peck, now playing through February 29, 2024 at Brooklyn Academy of Music,

30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn

• • •

Dreams of another world are always filled with martyrs from this one. Wherever they settle—in the chest, the throat, behind the eyes—the dreams nettle. Even if a tarnished progress must be conceded, it was not supposed to look like this. One need not rehearse the long and brutal history of interference and venality that ensured the near synonymity of “post” and “neo” as prefixes to “colonial.” It is enough to say that there are those who have died and whose names and nations have become shibboleths signaling both a history and a possible future.

Raoul Peck as a child in Lumumba: Death of a Prophet. Courtesy Janus Films.

Raoul Peck’s 1991 documentary Lumumba: Death of a Prophet traffics in these nominative talismans. It is at once a memoir of the director’s childhood in the Congo (then newly independent after nearly a century of brutal Belgian rule) and an attempt to find, if not the corpse of Patrice Lumumba (the independence leader who served as prime minister for less than three months before being executed), then at least some trace of his ghost. Comprising home movies as well as original and archival material, the film limns the rise and fall of the slain politician but is most concerned with history as a means to provide a glimpse of some world nobler than ours. In that one, the uranium mine in Katanga that produced the ore that the Manhattan Project used to develop the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not be reason enough to hang a noose around a nation. Near the beginning, Peck (who is the film’s narrator) says “Haiti, 1960” over a photo of his grade-school class and then “Leopoldville, capital of the former Belgian Congo” over home footage of the city. Peck was born on the island nation in 1953; by 1962, he and his family had moved to the Congo. Haiti, Congo: these are watchwords, imbued with all the hope, dignity, and terror of black revolt. And they are warnings, bearing in their brevity centuries of backlash. Lumumba is like that, too.

He held office for only one short summer in 1960 and was dead by winter. Although Peck gives him a holy title, he is not canonized as an all-knowing saint. If anything, through interviews with former Belgian government officials, he is depicted as perilously naive. A Belgian adviser tells a story about a night when Mobutu Sese Seko (the future dictator who would help orchestrate Lumumba’s assassination) drunkenly announced that he was placing the prime minister under arrest. Lumumba waived it all off as the inconsequential ramblings elicited by champagne. The word “tragic” arrives unbidden, but less because of a sense of fate than the repeated desire to whisper “if only . . .”

Jacques Brassinne in Lumumba: Death of a Prophet. Courtesy Janus Films.

Most archival documentaries, from the inventive to the rote, operate on the principle that their appeal lies in the supposed rarity of their footage, even if the cottage industry of licensing houses, with their exorbitant fees for little-seen images, often limits the filmmaker to using familiar ones. Innovative documentaries, like Peck’s, place themselves apart simply by taking these ready-made images seriously, as more than illustration. Peck uses some immediately obvious techniques to do so—freezing the footage, slowing it down, playing it silently—but also conceptually juxtaposes it to images that do not exist, namely the moment of Lumumba’s murder and the guilt or shame that might somehow hang over Brussels.

Juliana Lumumba in Lumumba: Death of a Prophet. Courtesy Janus Films.

“There are images,” Peck intones, “and those that make them.” The second clause is uttered over a busy station in Brussels and is ripe for the historically apt racialized reading: white Europeans, whether as artists or anthropologists, rode the coattails of colonials and came back with aesthetic and intellectual property, among other kinds. But in the context of Lumumba, the assertion is more complicated. Peck is utilizing these depictions of present-day Brussels as counter-images to the archive’s fevered murmurs. Over a black screen, he tells us, “The picture has been lost. The voice remains.” The declaration is nearly the organizing principle for Peck’s project. The film, tormented by Lumumba’s absence, tries to secure meaning from what traces have been left behind, as the bereaved are wont to do.

Still from Lumumba: Death of a Prophet. Courtesy Janus Films.

In at least some way, all films with people in them are about grief. A face is recorded in light and thus frozen, even as the real flesh is headed toward dissolution. You are already holding fast to what is gone. You are already mourning. The question is what to do with all this grief. Peck tries to produce images that cohere enough to establish a haunting where perhaps there is none. Over images of a wintry Brussels, he tells us, “The prophet roams this city.” Ghosts are typically tethered to the location of their demise. One would expect, then, Lumumba to roam Katanga, the site of his assassination. Peck reorients the spectral stipulations. Martyrs, he suggests, do not come back to haunt the place where the bullet was fired, but where the order was given. The repeated shots of Belgians are not libelous. No blame is directly ascribed. They appear in the film the way strangers do as you, bewildered on some calamitous day, search their faces for recognition of a fresh private disaster, even if you know that their anonymity and ignorance are just like yours. “Why can’t these descendants of the colonizers see the prophet?” is the easy question. The more worrisome one is, “Why can’t we?”

Patrice Lumumba in Lumumba: Death of a Prophet. Courtesy Janus Films.

The documentary hovers around the literal meaning of habeas corpus. Cinema, the Belgians, the Congolese collaborators—all failed to produce Lumumba’s body. They destroyed the evidence of their crime, but in so doing turned his murder into a disappearance, and what has slipped from view might still lie just beyond the periphery. At least so one hopes, or fears, depending on what has gone missing. A decade after Lumumba: Death of a Prophet, Peck directed a more traditional biopic. That narrative film fills in the blanks. Lumumba’s captors drive him out into the woods, their headlights piercing the night and illuminating the trees that will serve as makeshift pillories. He is tied up and gunned down, and his erstwhile ally Mobutu Sese Seko cements his grip on power by commemorating Lumumba as a national hero.

Even adjusting for inflation, the four million dollars it cost to bring the biopic to the screen, and so to finally produce an image of the body, is not real money by Hollywood’s standards. But as stirring as the performances are, it feels as though Peck got closer to the missing picture a decade earlier, in the cuts to black, in the Belgian faces staring back at his camera, in Brussels’s indifference. At one point, a camera captures the view from a rapidly moving train. Snow has settled on the rails. Trees whip by. The scene ought to be idyllic. Then Peck asks, “Is a holocaust the only unit that can measure the human race?” The question is rhetorical, or perhaps too frightening to answer. Melancholy comes easily to the left, which, in every generation, must rise to a grim occasion in the full knowledge that history’s lessons are not to be learned but enforced. Lumumba is dead, but the next prophet lives. If there is to be some other unit of measurement, we must make it so.

Blair McClendon is an editor, filmmaker, and writer. His film work has screened at Sundance, Cannes, Tribeca, TIFF, and other festivals around the world. His writing has been published in n+1, the New Republic, the New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere. He lives in New York.