Megan Milks

Megan Milks

Octavia Butler’s Afrofuturist novel goes graphic.

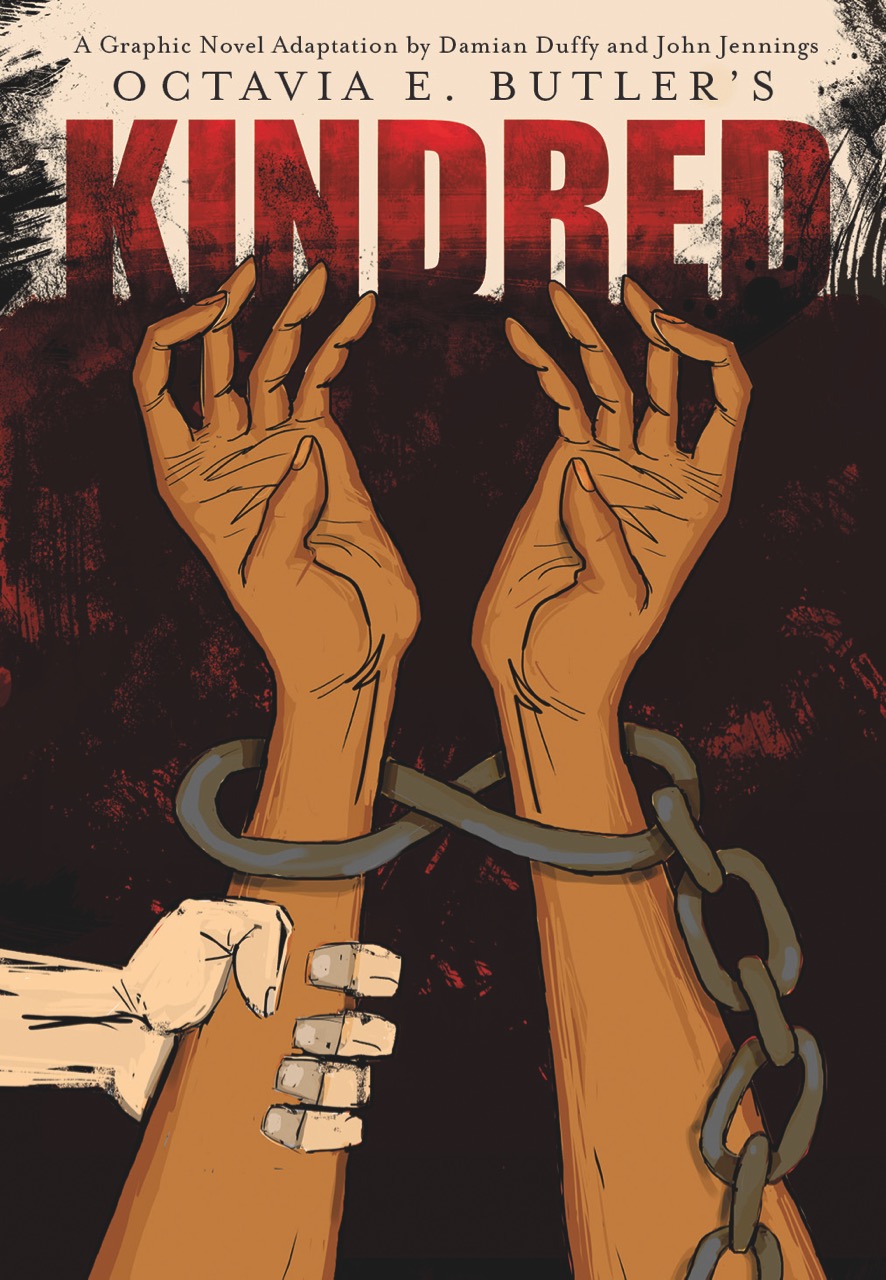

Kindred, by Octavia E. Butler, adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings, Abrams ComicArts, 240 pages, $24.95

• • •

It’s been thirty-eight years since the publication of Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred (1979), her fourth and most widely read novel. The number is significant: it’s a measure of time Butler herself used to predict major change. She set the dystopian Clay’s Ark (1984) thirty-eight years into the then-future because, her letters tell us, she felt this was long enough for the world to have changed drastically while still remaining recognizable. Kindred has now been adapted into a graphic novel by collaborative team Damian Duffy and John Jennings, bringing what Butler called her “grim fantasy” to rich visual life. Scripted and lettered by Duffy and drawn, inked, and colored by Jennings, the adaptation is mostly faithful to the original text, delivering a captivating graphic interpretation that both revivifies Kindred and introduces it to a new audience.

We could point to a number of relevant major events that have occurred in the gap between 1979 and now: in addition to the Internet and the 9/11 attacks that ushered in a new age of global terror, the United States has witnessed a dramatic resurgence of racial violence and discrimination concurrent with a relegitimized vision of white supremacy. Science fiction and comics have gained more cultural status. And we have lost Butler—storytelling genius, sci-fi and Afrofuturist master—who died in 2006.

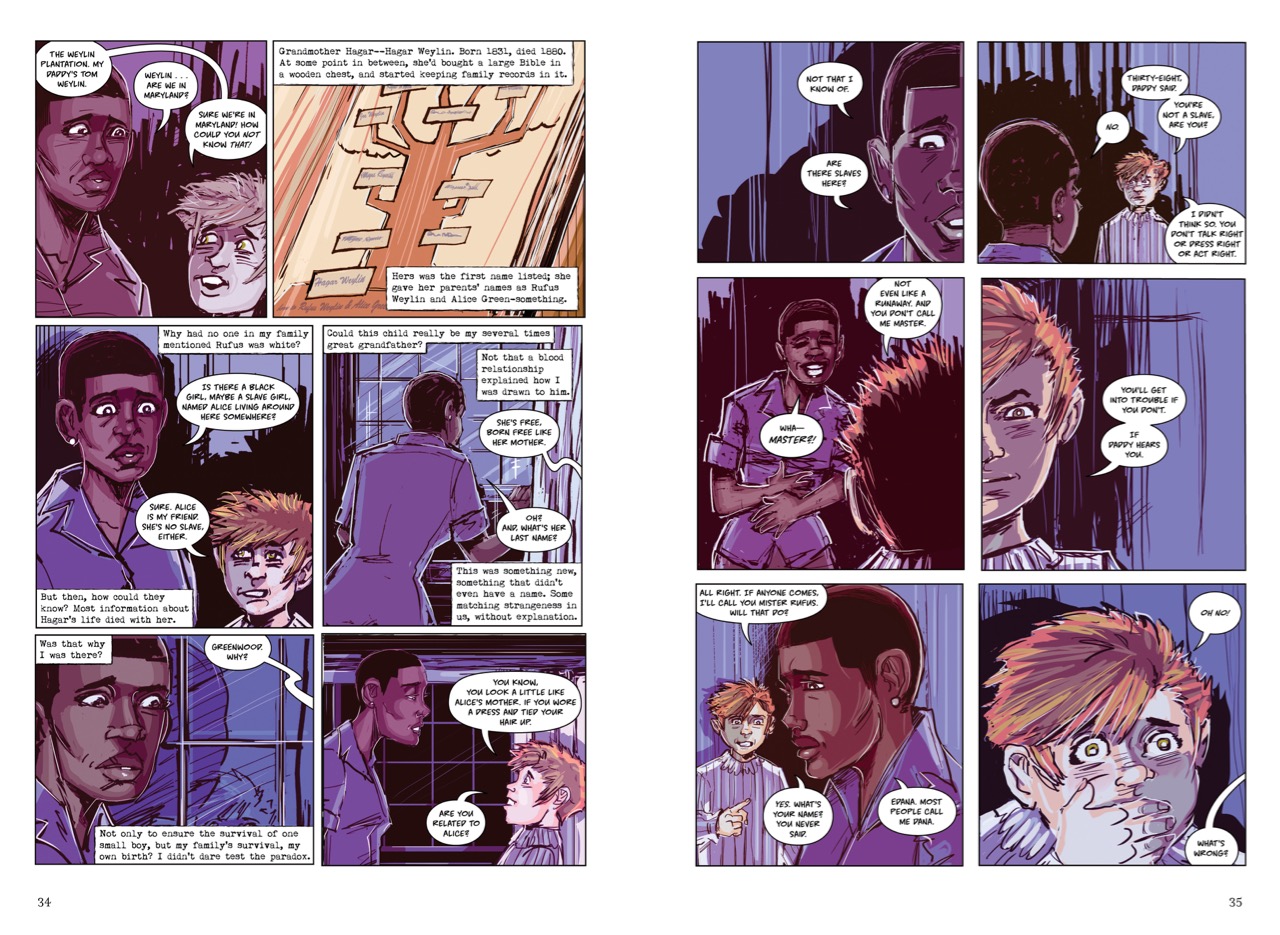

© Abrams ComicArts, 2017

Kindred is the story of Dana, an African-American writer and obvious proxy for Butler herself. It’s 1976, and Dana is living with her white husband in southern California when, on her twenty-sixth birthday, she finds herself yanked without warning to a slave plantation in antebellum Maryland. There she meets—and saves—a drowning white boy named Rufus Weylin. Dana soon realizes Rufus is her distant ancestor. As the novel progresses, she comes to understand the logic of the temporal wormhole she’s involuntarily stuck in: when Rufus believes his life is endangered, she is called to him; once there, she can return to 1976 only when she believes her own life is threatened. In order to preserve both her family history and her own birth, Dana must keep Rufus alive: neither an easy task, as Rufus is reckless and mercurial, nor an appealing one, as he and his family are slaveholders who exercise power over her, often violently.

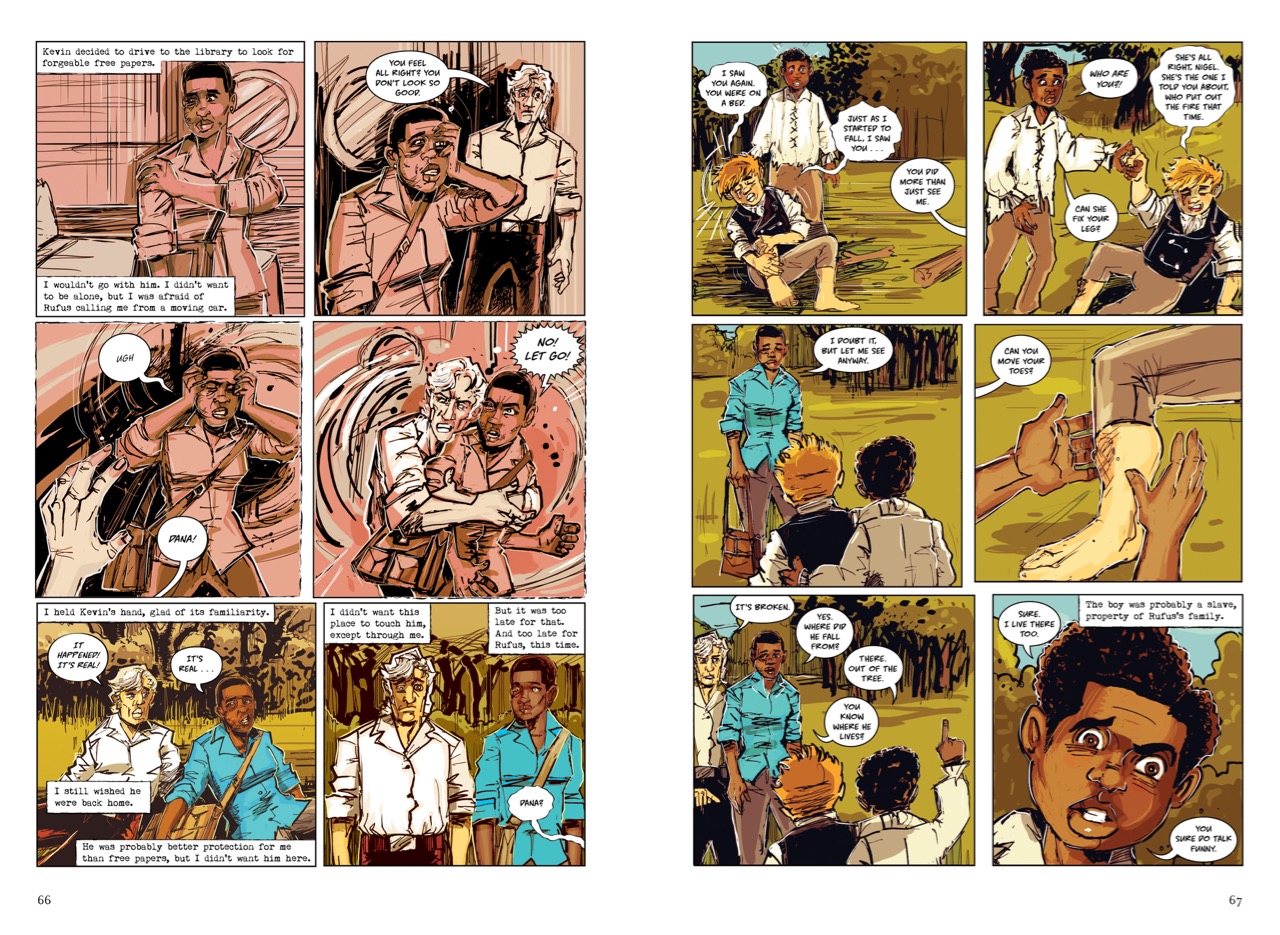

In Kindred, Butler recenters the time-travel narrative, historically by and about white men, around black female experience; and introduces an explicitly contemporary, reflexive frame to the neo-slave narrative. It’s an ingenius project, and Butler is a remarkably complex storyteller. Yet her style can sometimes feel a bit wooden, favoring extended dialogue sequences and utilitarian prose. In Duffy and Jennings’s adaptation, the story is streamlined and newly invigorated. Some secondary characters have been collapsed, and many of Butler’s long sequences of dialogue have been trimmed down and presented inventively, for example, with hydra-headed speech balloons. Meanwhile, Jennings’s depictions are emotive and kinetic. His frenetic, at times furious lines skillfully illustrate characters’ shifting moods—we see Dana’s anger flatten to resignation, Rufus’s affection sour to hateful petulance. Jennings’s dynamic style also contributes movement to sequences where there is little action.

But there is action here, plenty, often ugly and emotionally challenging. Butler’s worlds were heavily influenced by comics; many of her characters are superhuman, their abilities ranging from telepathy, hyper-empathy, and psychometry to shapeshifting, body swapping, and flying. It’s appropriate that her literary work is being translated into graphic novel form, though Kindred is perhaps an unlikely first candidate. While it is her most commercially successful and widely read novel, it’s also the least fantastic.

If Kindred is her most realist work, its realism is not tremendously visceral; Butler deliberately produced what she felt was a sanitized representation of slavery—she felt it needed to be palatable enough that people would actually read the book. Jennings, an Eisner Award winner and something of a powerhouse in indie comics, visualizes the story with a cartoonish quality that agrees with Butler’s original. Like Butler, he avoids representing the cruelties of slavery through visceral realism, opting to be strategic about the amount of violence depicted—much of it off-panel or conveyed through characters’ emotive responses. Still, the impact of violence on the body is very much on display throughout. And, without relieving the story of its trauma or grimness, the at-times exaggerated expressions and use of exclamations and written sound effects provide some valuable distance.

“History is another planet,” Butler often noted in talks. When Dana first finds herself transplanted to antebellum Maryland, her alienation is profound. But it quickly dissipates as she assimilates into this new world, and she even begins thinking of the Weylin house, not without horror, as “home.” Jennings and Duffy highlight this new normal by presenting the nineteenth century in full color. Interior scenes, for example, are often warmly alluring with the bold yellows and oranges of the strong candlelight of pre-electric living. In contrast, Jennings colors the 1976 scenes with muted sienna tones that have a worn-out look. If the historical past is insistently alive, Dana’s present is exhausted from it.

© Abrams ComicArts, 2017

As, perhaps, is ours. Reading Kindred now in this new form, with those thirty-eight years between us and the book’s first appearance, we are confronted with questions about progress and cyclicality. Jennings’s cover art, a black woman’s wrists locked up by a cuff shaped like an infinity symbol, explicitly points to the ways the novel addresses the legacy of chattel slavery in the US—its ongoingness, its lasting effects. After her first visit to the past, Dana returns shivering and frightened. “Whatever it was,” she cries, “it almost killed me!!! . . . And it could happen again. Any time!”

In her many drafts of Kindred, Butler experimented with alternate endings in which Dana was able to intervene into the historical past in more transformative ways—for example, in one version, Dana brings her ancestor Alice into 1976 with her, saving her from Rufus’s brutality; in another, a second time traveler shows up to help slaves escape. She abandoned all of them. History would absorb neither Dana’s nor Butler’s interventions; the task was not to transform history but to survive it. And Dana does survive, though not wholly intact. When she returns from her final trip, her left arm is crushed by a wall.

At heart, Kindred is a story about epigenetic trauma, the idea that historical trauma is coded into our genes. Here this plays out literally: Dana’s genealogical inheritance claims her. In a sense, this is true, too, of Butler’s literary inheritance, her fusion of science fiction, African-American history and literature, and contemporary black feminist ideals. Duffy and Jennings’s adaptation claims Kindred for another literature, bringing it into the arena of comics and luring new readers through its temporal vortex.

© Abrams ComicArts, 2017

Megan Milks is the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, winner of the 2015 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Fiction and a Lambda Literary Award finalist, as well as three chapbooks, most recently The Feels, an exploration of fan fiction and affect. Milks is fiction editor at The Account, and editor of the books The &NOW Awards 3: The Best Innovative Writing, 2011–2013 and Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives.