David O’Neill

David O’Neill

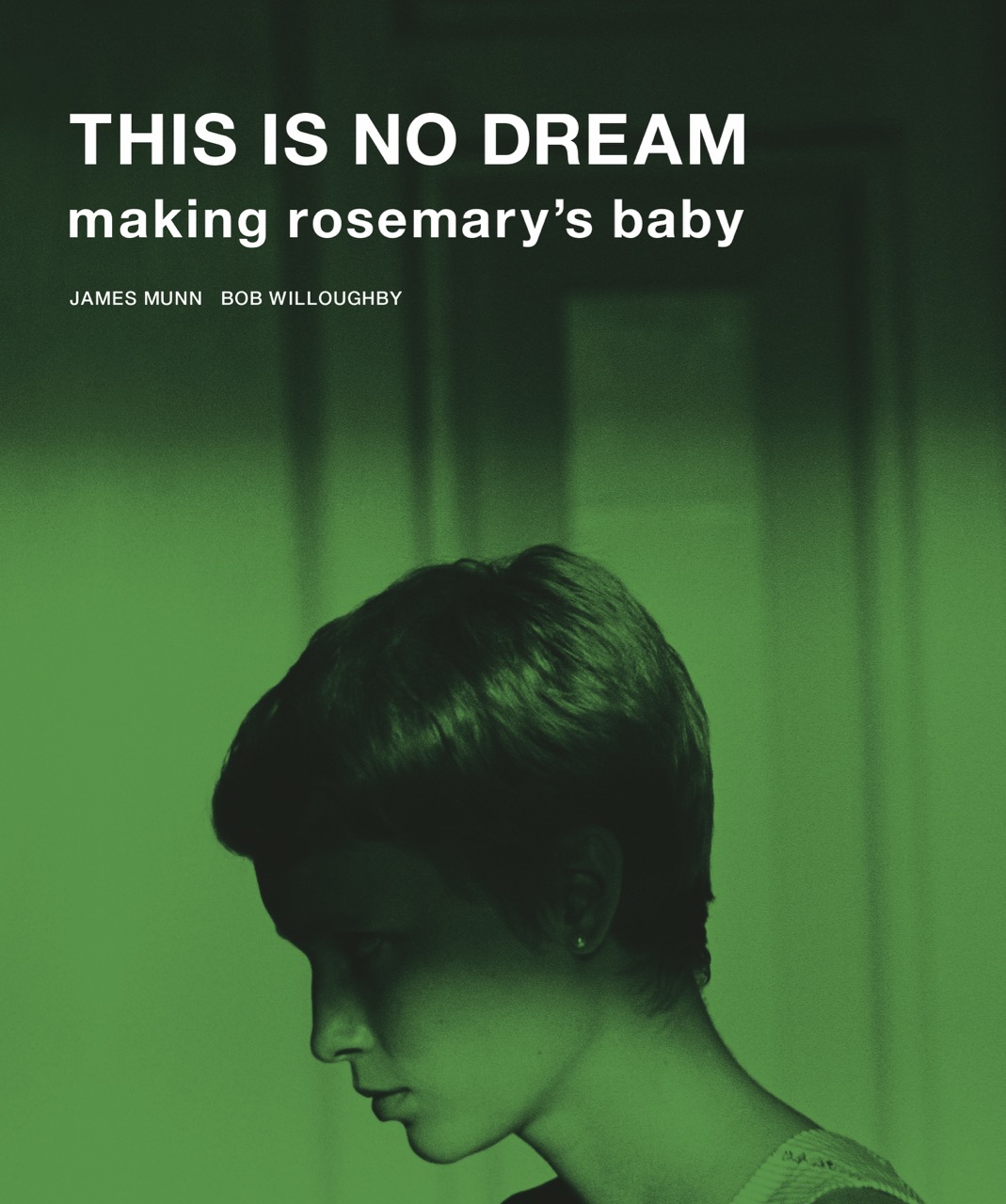

The devil wears onesies: a look back at the birth of Rosemary’s Baby.

This Is No Dream: Making Rosemary’s Baby, by James Munn, Reel Art Press, 207 pages, $49.95

• • •

My mother was twenty-seven in 1968, the year Rosemary’s Baby came out. She was an unnervingly smart and slyly independent Irish Catholic mother. The political upheaval in the streets and the manic new breed of movie on the screen didn’t speak to her, but I always wondered if she could have seen herself in Rosemary. Mia Farrow’s portrayal of an endangered Catholic newlywed perfectly distills the anxiety of the era’s gaily constrained femininity, a nameless frustration my mom always tried to outrun.

Mia Farrow as Rosemary Woodhouse in Rosemary’s Baby. Photo: Bob Willoughby. © MPTV Images / Reel Art Press.

An impossibly chic Farrow is the reason to watch the film now. Wearing Peter Pan–collared pajamas by night, mod A-line minidresses by day, and sporting a shocking strawberry-blonde pixie haircut, she gives a musical performance that looks like acting: she’s in command of every syllable—her voice a genius instrument of range, tempo, and emotion. Early on, Rosemary brags about her husband’s new acting gig in a singsong that becomes halting, sulky, and then trails off miserably: “I bet even Laurence Olivier is vain and self-centered. It’s a difficult part . . . and, naturally, he’s preoccupied, and he, well, preoccupied . . . ” Director-screenwriter Roman Polanski and schlock-maestro producer William Castle probably thought they’d cast someone malleable, a doe-eyed waif straight from TV’s Peyton Place. Just twenty-two years old at the time, Farrow would pal around on the Rosemary’s Baby set with her kitten, Malcolm, before the cameras rolled. When they did, she suddenly became a fully formed artist, ably channeling the terror of a secret hell.

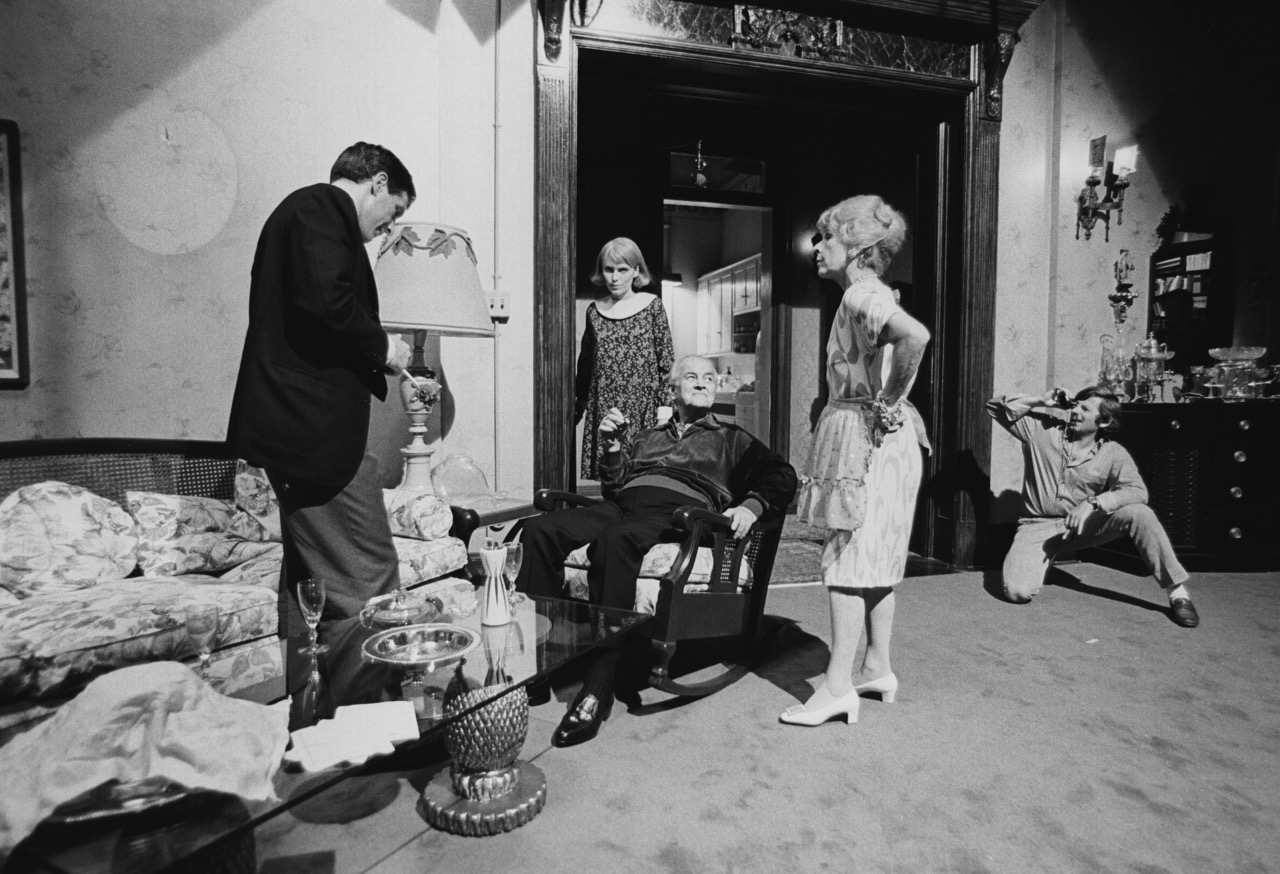

The movie, based on Ira Levin’s bestselling novel of the same name, was Polanski’s first American feature. It’s Hitchcockian by way of the French New Wave. We follow a young couple who land an Upper West Side apartment and suffer stifling attention from the eccentric husband and wife next door, who are not only fiendishly intrusive, but also literally witches. Minnie and Roman Castevet (Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer) chatter and flatter; Rosemary’s wiseacre husband, Guy (John Cassavetes), eats it up and seems to become secretly aligned with them. Everyone—satanic or not—wants to know if there’s a baby on the way.

John Cassavetes as Guy Woodhouse and Sidney Blackmer as Roman Castevet in Rosemary’s Baby. Photo: Bob Willoughby. © MPTV Images / Reel Art Press.

Soon, there is: Rosemary is drugged and raped in a trippy montage that, despite its silly monster-movie props and arty aspirations, is sickening, especially considering Polanski’s 1977 guilty plea to unlawful sex with a thirteen-year-old girl. Rosemary soon discovers she is pregnant and immediately feels something is very wrong. Is there? The plotting is tick-tock tight with intriguing clues—a foul-smelling pendant, suspicious smoothies, and a dramatic Scrabble tile reveal. It’s no surprise when she gives birth to the Antichrist.

This Is No Dream: Making Rosemary’s Baby, which will be published this summer for the film’s fiftieth anniversary, recounts its casting, shooting, editing, and reception. (Polanski’s movie will screen at the Quad Cinema in New York on July 13 and 16 as part of the series “The New York Woman.”) Author James Munn merrily treats every studio machination and each piece of trivia like a bold-face revelation. But the book’s real draw is the portfolio of on-set photos by Bob Willoughby, who documented the production in pleasingly aslant compositions with a Garry Winogrand–like eye for unselfconscious—or quietly berserk—moments. We see Polanski intently sizing up shots, Farrow looking worried as she holds a Time magazine with “Is God Dead?” on the cover, and Cassavetes embracing the director in a mock love scene. In one telling image, R.P. and J.C. argue while Farrow looks on, tired and annoyed, from bed.

Filming in the Castevets’ apartment for Rosemary’s Baby. Photo: Bob Willoughby. © MPTV Images / Reel Art Press.

Polanski and his male lead quarreled often. Cassavetes was working on his 1968 film, Faces; if you watch five minutes of that freewheeling drama, you’ll see why he’d be such a pill on a Hollywood set. (As Willoughby astutely observed: “Every scene seemed pivotal to him.”) He’s great nonetheless: with a salesman’s smile, his chin tucked in, and his eyes peering up from beneath peaked eyebrows, Cassavetes looks cartoonishly evil. But there’s real menace. He gets Guy’s barely suppressible rage, that of a grandiose thespian drowning in his own mediocrity, and the driving distrust of domesticity such a character might privately nurse.

John Cassavetes as Guy Woodhouse in Rosemary’s Baby. Photo: Bob Willoughby. © MPTV Images / Reel Art Press.

While Cassavetes plays a ham actor and artist manqué, Farrow portrays a woman trapped in an unforgiving role. Her part calls for extravagant suffering: Rosemary is in terrible pain that her doctor dismisses; she’s isolated; and Guy opposes the idea of even getting a second opinion. She always views her experience through the dirty window of self-doubt. And yet the world wants a happy mother-to-be. Farrow makes the most of the thin, pulpy lines the script supplies. Rosemary’s practiced cheerfulness is layered with notes of resignation, resentment, and dreamy disassociation. After pretending to finish a chalky-tasting chocolate mousse made by Mrs. Castevet, Rosemary sweetly says to Guy, “There, Daddy. Do I get a gold star?” Farrow delivers the line coolly and carnally; it also stings. Mostly, Rosemary’s rebellion is on the sly—rolling her eyes during dinner and snubbing the nosy couple when she can. There’s only one moment of true release: Rosemary spits in Guy’s face. By then, it’s too late.

Mia Farrow as Rosemary Woodhouse in Rosemary’s Baby. © MPTV Images / Reel Art Press.

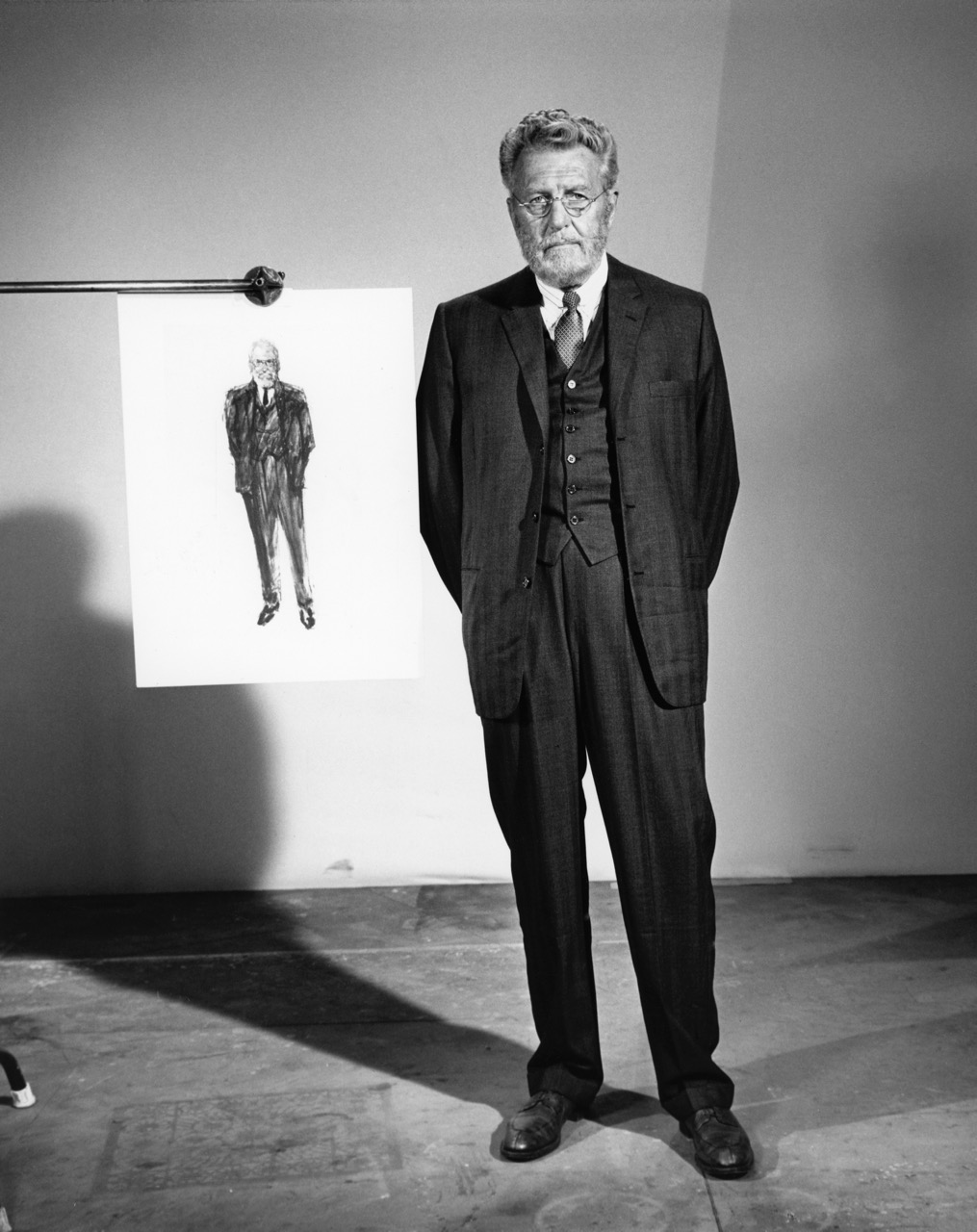

This Is No Dream recounts how Farrow’s real-life husband, Frank Sinatra, was annoyed by her independence. He pressured her to leave the film, but she refused, so he sent a lawyer to the set with divorce papers. Polanski says Farrow was bothered most by how Sinatra sent “one of his flunkies” to end the relationship. It was “like firing a servant. She simply couldn’t understand her husband’s contemptuous, calculated act of cruelty.” Rosemary finds freedom, too, but it doesn’t last long. She explains the witches’ scheme to Dr. Hill (Charles Grodin), who pretends to believe her and then rats her out: as she naps in his office, he summons Guy and a satanic obstetrician, who says, “Come with us quietly, Rosemary. Don’t argue or make a scene.” Defeated, she leaves with them. Dr. Hill tells the men, “I’m glad I could be of help.”

Ralph Bellamy as Dr. Sapirstein in Rosemary’s Baby. © MPTV Images / Reel Art Press.

Polanski said he wanted Rosemary’s Baby to be “ambiguous”: we’re supposed to wonder whether Rosemary is going insane, à la Repulsion, the director’s 1965 film. But how could we? We know control and extreme gaslighting when we see it. And Farrow’s spiky, desperately honest acting leaves no question that there’s a plot against Rosemary. Doubting her hardly even occurred to me. Growing up, I saw my mom feel sick and strange in a man’s world—the night after I first watched the film, I dreamt she was ill. (My subconscious is not subtle.)

Rosemary’s Baby was released in June of 1968, the same month that the New York Radical Women published Notes from the First Year. That Halloween, the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (W.I.T.C.H.) was founded. The group hexed Wall Street, pranked wedding fairs, and protested Playboy Clubs. The term second wave was coined and many new movements were born. My mother says she never “got” feminism. She’s always suspected that the conspiracy of mean-spirited men was all in her head.

David O’Neill is a writer in New York, an editor of Bookforum, and the coeditor of Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz, published by Semiotext(e).