Michelle Orange

Michelle Orange

A climate-crisis anti-memoir by novelist Lydia Millet makes a case for humility before nature.

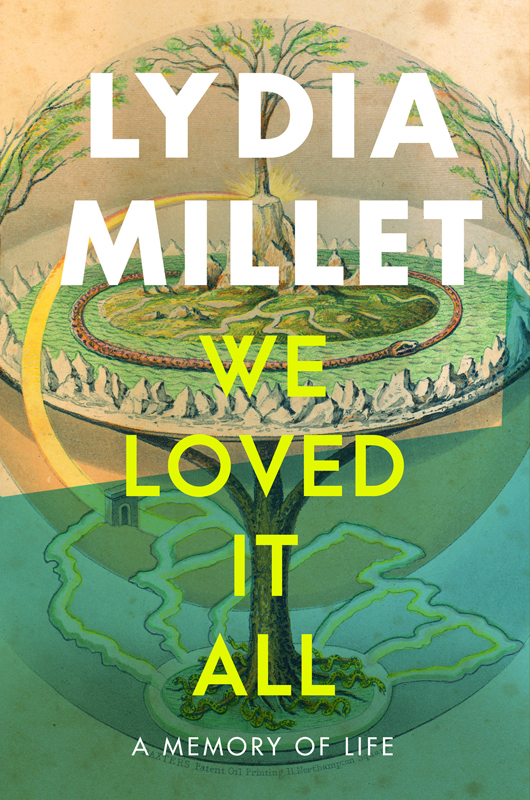

We Loved It All: A Memory of Life, by Lydia Millet,

W. W. Norton, 254 pages, $27.99

• • •

To be a person of any conscience and basic or greater means, today, is to hedge every hour, to barter through each day. It is to call to mind visions of well-meaning individuals shuffling cliff-ward in great hordes, adding solar panels and compost worms to cart even as the ground opens beneath their feet. The “we” of We Loved It All: A Memory of Life, novelist Lydia Millet’s first nonfiction book, would seem to invoke those of us similarly lost in the hedge of modern existence, feeling trapped even by the stories we tell and are told about what has happened, and why, and what is yet to come. Arranged in fragments that seek a centripetal narrative force, the book points to the central dodge on which an individualist, consumption-driven society depends, the feats of stamina and will required to refute our belonging to a collective we cannot escape or transcend. It suggests, through vignettes layered to riddle-like effect, that humankind’s retreat into the myths of sovereign, cosseted selfhood has in fact intertwined us as never before. That we are more tightly bound to each other and to all life on this planet—and are more deluded on that point—than we have ever been.

In a 2022 New York Times Magazine profile, Millet described how her day job with the Center for Biological Diversity, a conservation group focused on protecting endangered species, has helped offset her feeling that to be only a writer is too “self-indulgent . . . It’s not the same as action.” Yet Millet is most comfortable hovering somewhere in between the two vocations, being neither wholly an activist, “due to my aversion to slogans and crowds and open conflict,” as she states in We Loved It All, nor “a constant participant in the establishments of publishing or writing,” given that she is based in Arizona. Freewheeling in structure but often plodding in affect, the book, billed as an “anti-memoir,” proposes a sort of hedge between story and action: a work of climate change–themed nonfiction that avoids argument, doomsaying, or much in the way of proposed fixes. Instead, Millet seeks to reflect in prismatic technicolor the predicament of the “we” who, much like the author, are desperate for a sense of how our precious agency, having helped accelerate the problem, might now be deployed in service of its remedy.

Some part of that work, Millet suggests, is bound up in the stories we tell about ourselves, “their biases and contradictions and how often, though we steer ourselves by their landmarks, they diverge from our lived experience.” What might it mean to shake free of what we believe we know, or value, or need, and allow for other stories, other possibilities? Millet intersperses the potted histories, creaturely interludes, and bits of social observation that comprise We Loved It All with personal anecdote and revelation, freely alternating between “we” and “I.” The transitions tend to jar; whole chapters refuse to gel. In one of these, Millet moves between discussion of gun and hunting culture, a visit to a shooting range, the author’s random, “vicious” stomping of a toad as a child, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the connection between anti-intellectualism and American notions of personal liberty, the insanities of pet ownership, pesticides and the Millet family peach farm, the scourge of the boll weevil, car obsession, and a riff on eulogizing the fossil-fuel “monster that we’ve made in order to move on.” The reader may come to dread those section breaks that separate, for instance, a moving account of the mostly silent, morphine-fogged last weeks of Millet’s father and that of a massive bat die-off during Australia’s 2020 heat wave.

Those wondering if any form of narrative or arrangement of data might relay the urgency of the climate crisis and a sixth mass extinction in newly galvanizing terms—and, perhaps, if meaningful action might resemble reading a book like this one—will likely be disappointed by We Loved It All, which finds potency in its wish to mourn and refusal to panic. The story Millet has chosen to tell is recursive, hopeful yet uncertain, admitting of its narrator’s contradictions, her place among “those of us who—guided by wanting and getting—let the rest of the world slip away.” In its focus on what she refers to as “the others” and “the beasts,” it is in some ways a counterpoint to a work like David Wallace-Wells’s best-selling The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming (2019), which Millet references but does not name. Where Wallace-Wells exemplifies the exceptionalist, “save ourselves” slant of many such texts (“The world could lose much of what we think of as ‘nature,’ as far as I cared,” he writes, “so long as we could go on living as we have in the world left behind”), if Millet argues for anything it is for a corrective “humility before nature,” the turning outward of our fears, the embrace of a story “that invites us not to want to be better than. But to want to be good.”

Though she doesn’t invoke him by name either, the spirit of John Berger animates much of Millet’s thinking on how we look—and have stopped looking—at the beasts among us, the “centuries-long conflict within ourselves over the other animals’ ongoing reduction into objects.” We Loved It All teems with fun and less-fun facts about those animals, from the mysteries of the blue whale to the revelation that in 1936 the last Tasmanian tiger died after the zoo housing it denied support to “the only person willing and able to take care of it . . . on the basis that she was a woman.” But Berger is most present in the premise of a book that insists on hope and solidarity as their own ends, as a link to a future that is never guaranteed. For Millet, more and more, “writing takes the form of prayer. As in a dark booth, first comes a confession. And then an incantation.” In many ways a book of those hymns, We Loved It All echoes Berger’s belief about the power of resistance: whether raising a pen or a banner, one protests less to effect the justice one seeks than “to save the present moment, whatever the future holds.”

Michelle Orange is the author, most recently, of Pure Flame: A Legacy (FSG).