Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

Motherhood, nature, and the helpful people of Maine: a collection of essays by the poet Camille T. Dungy.

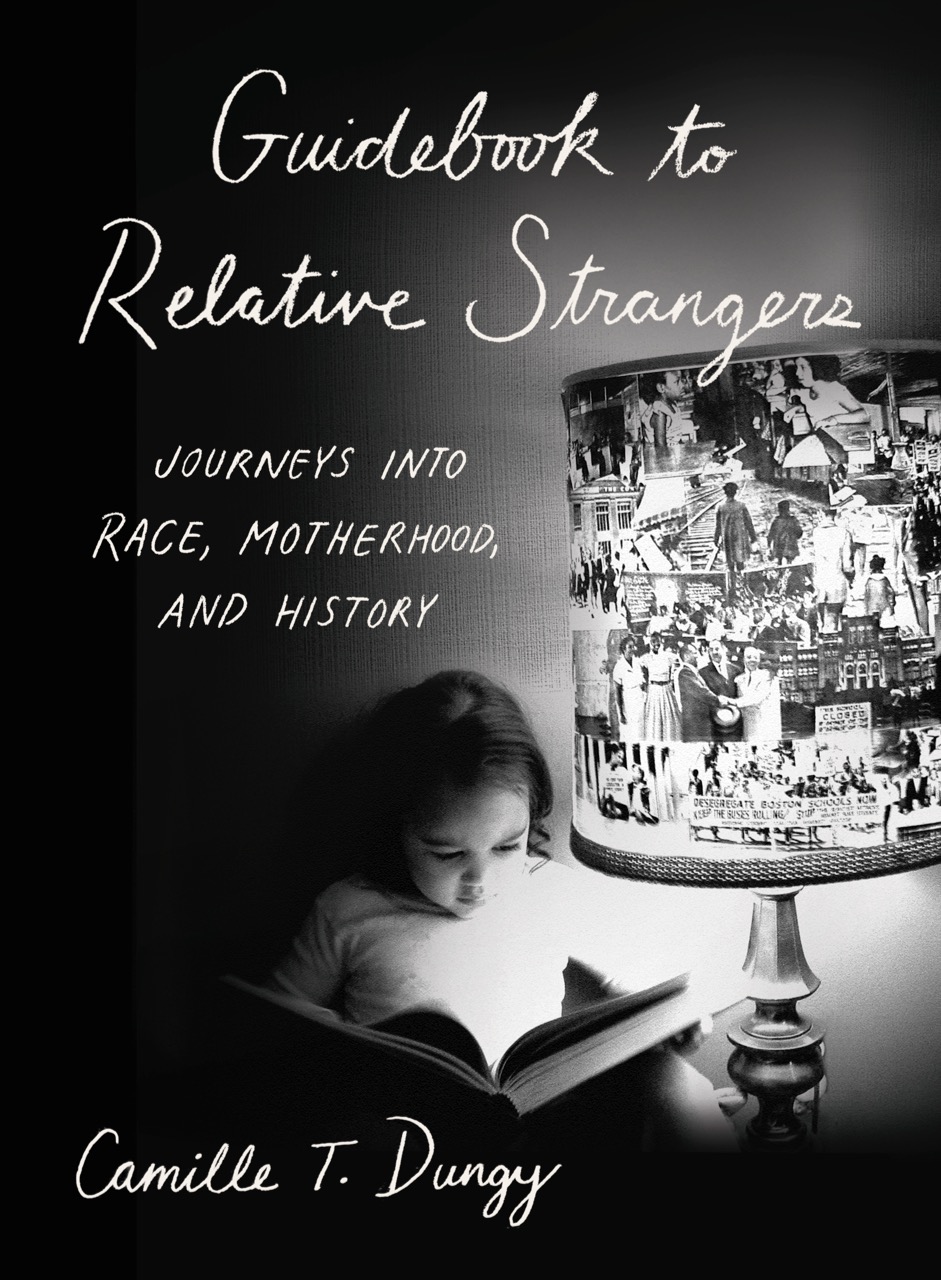

Guidebook to Relative Strangers, by Camille T. Dungy, Norton, 240 pages, $25.95

• • •

While pregnant, Camille T. Dungy fears isolation and estrangement: “I felt sure that the woman I’d worked thirty-six years to become would be pushed aside by someone else.” Yet when this poet, professor, public speaker, and holder of advanced degrees becomes a mother, she welcomes her altered identity. Motherhood, she says in her new essay collection, Guidebook to Relative Strangers, is like umami, the flavor that comes from stewing meat down to its essence. “I don’t know if I can define myself anymore, now that I’m your mother,” she writes, addressing her infant daughter. “You’ve consumed me. Being your mother has cooked me right down to the bone.”

Is this an erasure or a distillation of the self? Either way, there’s bliss in it, but it’s scary, too. How can a writer have a voice when she has been both “eaten up” and defined by another? Dungy’s essays can be read as acts of recollection that gather a new self from the scattered remains. Some writers on motherhood (Rivka Galchen, Rachel Cusk) dive deeply into the newness, intensity, and mutual orientation of the mother-child encounter. But in these wide-ranging and delightful pieces, Dungy draws her mothering into the breadth of her experience: as a Californian, the daughter and wife of academics, a traveler and observer, a hiker, a black woman with a passion for history and the natural world.

The changes of parenting can be generative as well as disruptive. Before you know it you are investing meaning in objects you once thought trivial: you’re taking an inexplicable interest in a tiny snowsuit, developing an attachment to a blue stuffed dinosaur. You’re making new juxtapositions, improvising like mad, leaping the gaps between selves. For Dungy this means interpreting comments from strangers about her child’s hair, reconsidering the nineteenth-century white settlement of San Francisco from a maternal point of view, or reciting Wallace Stevens’s “The Idea of Order at Key West” while rocking the baby to sleep.

In the title poem of her new collection Trophic Cascade (2017) she compares motherhood to the revival of the Yellowstone ecosystem after the reintroduction of the wolf. “All this / life born from one hungry animal, this whole, / new landscape, the course of the river changed.” She has published four books of poetry and edited two anthologies, including Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry (2009), a book that redresses the relative absence of black voices from anthologies of the genre. The natural world is part of the context of her mothering, but in Guidebook to Relative Strangers it is also a theme in its own right, as a source of poetry and strength, or alternately of alienation and danger.

Many of Dungy’s essays in Guidebook are grounded in specific places, as if the question she’s asking is as simple as: Where am I? In “Writing Home,” previously published in Black Nature, Dungy tells us she grew up in Southern California, with open space just outside the back door: hills and bluffs that hadn’t yet been developed, growing with wild poppies, tumbleweed, “desert oak, prickly pear, eucalyptus, sage.” If at times she felt like an outsider among the other residents of mostly white Orange County, she knew herself to be “at home in the language of sky and mountaintop and sea.” She became a poet partly to put words to the joy she felt in this landscape, along with the pain of displacement. After she moved to Iowa with her family as a teenager, she felt she’d lost not only her territory but the source of her poetry. “The language of place is a slow speech to learn. Iowa is blue uninterrupted, blue talking all day and a darker blue still talking through the night,” she recalls. “I moved to Iowa and didn’t write for months. When a poem finally came, it was written in a different tongue.”

Race troubles her relationship to nature, she writes. “I am black and female; no place is for my pleasure. How do I write about the land and my place in it without these memories: the runaway with the hounds at her heels; the complaint of the poplar at the man-cry of its load; land a thing to work but not to own?” Into an essay on birding she weaves the story of a lynching in Minnesota. In an essay on fire, she writes that she can’t enjoy a bonfire in the Virginia woods because she can’t see it apart from a Southern rural history of terror.

Yet Dungy refuses to be displaced. A generous and clear-sighted observer, she seems peculiarly at home when she’s writing about her travels: to Ghana, Alaska, Presque Isle, Maine. In two long essays she records a trip with her infant daughter to give a reading in northern Maine. While she explores the state’s abolitionist history, she also describes the excessive, anxious helpfulness of the white people she meets on the way. On the plane, in the airport, at a café, they ask about and lavish praise on the baby as a way of expressing their surprise at seeing a black woman in their town, and their desire nonetheless to make her feel welcome.

In “A Good Hike,” Dungy gets an early taste of how mothers come to depend on others: husbands, grandparents, complete strangers in airports. A few weeks pregnant, on a hike with a group of environmental writers, she at first feels powerful. “I lose track of my own inhibitions” in the outdoors, she writes. “I become more willing to test my own limits.” But when she falls and breaks her ankle she becomes dependent on this group of “relative strangers” to get her out. Her dependence, and her uncomfortable awareness of being the only black woman in the group, is rewarded with the other hikers’ care: they prove “to be people I could trust with my body.” In this warm and clear-sighted essay Dungy suggests that humans in the woods are like humans in the midst of parenting: they become part of something larger than themselves, but at the cost of any illusions they may have had of their own autonomy.

Julie Phillips is the award-winning author of James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. She lives in Amsterdam, reviews fiction for the Dutch newspaper Trouw, and is working on a biographical book about creativity and mothering. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Ms., and The Village Voice, among others. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.