Ben Ratliff

Ben Ratliff

Shrieks, chants, guitars: the experimental Japanese musician’s first album is reissued after thirty-six years.

Keiji Haino, Watashi Dake?, Black Editions

• • •

The first thing you hear on “My Refuge,” the first track from the 1981 record Watashi Dake?, the first solo album by the Japanese musician Keiji Haino, is a brief, adrenalized shriek. It comes through a microphone and a buzzy amplifier, and it suggests something like surprise or horror. It is an alarming sound, but not as alarming as the suite of actions that follow it.

Watashi Dake?, long out of print and just reissued on vinyl by Black Editions, means “Only Me?” In it, he makes a powerful suggestion that a musician, in any and all moments, can choose not to dilute his own mystery. I think of Haino as an improviser, but I value him greatly for being so stylishly disinterested, for so long—since the early 1970s—in claiming any established language or practice of improvised music. The album is primarily a one-man studio recording, mostly just voice and electric guitar, with a few live tracks. “My Refuge” was recorded at the Goodman club in Tokyo. After the first cry, for several minutes Haino whimpers and gasps, letting silences open and bloom in between. He is emoting Japanese words, in a high whimper and warble: among them are “my body’s axis / twisted in on itself.” At the middle of the track he sings one tense, piercing high note.

Then silence, for forty seconds. I would like to point out again that “My Refuge” is the first track on a musician’s first solo album. There are forty seconds of dead air at its climax. Following that, fifteen seconds of rustling. What is it? Unclear. Then Haino’s voice returns in much the same way as before, with feedback squeaks from the amplifier. At the end, another shriek, cropped by turning off the microphone switch.

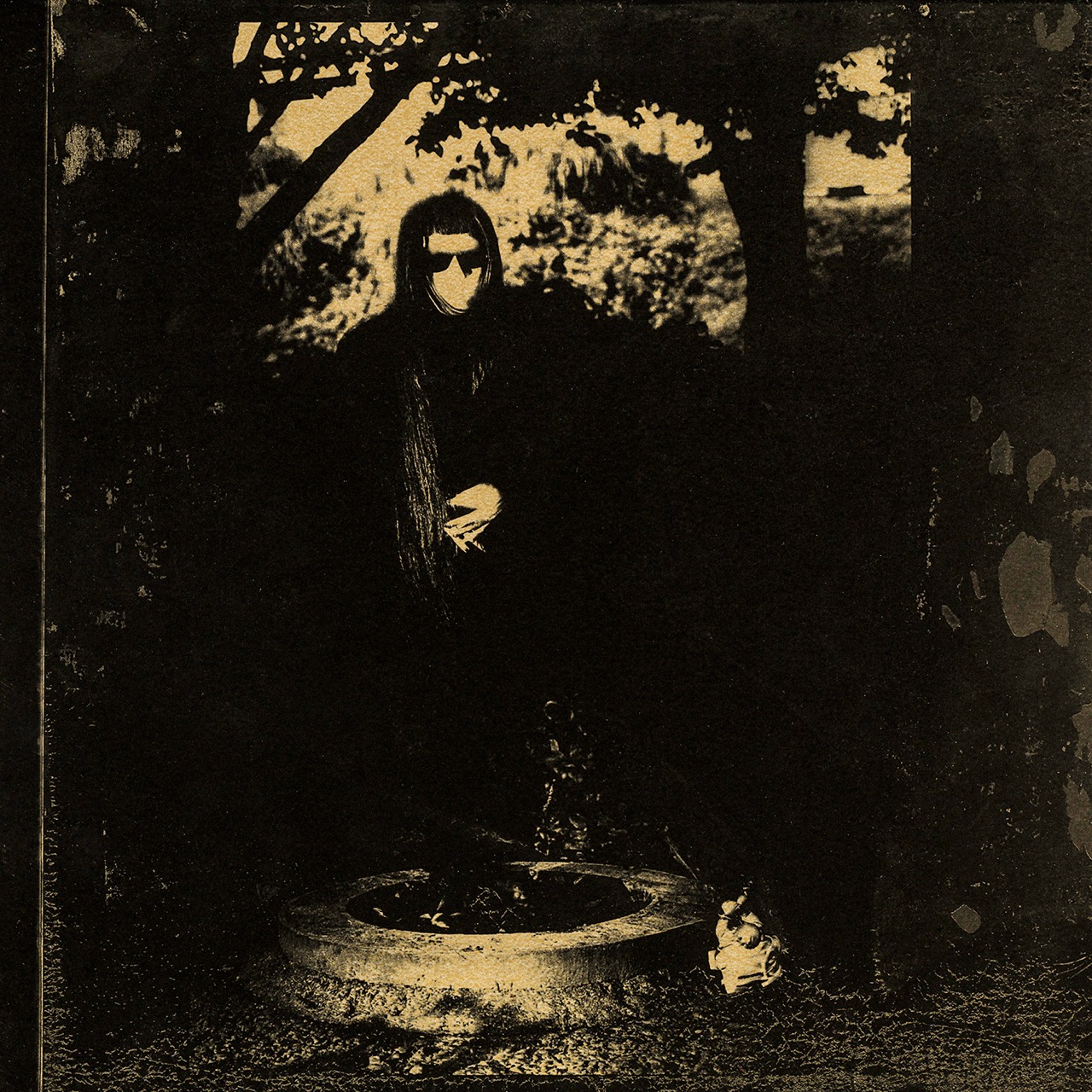

In the cover photos of Watashi Dake?, Haino looks much the same as he does today: small and slight, with black clothes, dark sunglasses, long hair and severe bangs, which have now gone gray. If you see him in a solo performance, he may use chimes, frame drums, guitars; or, as he did four years ago at Issue Project Room in Brooklyn, theremin-like synthesizers and various microphones. But the instrument doesn’t matter that much. He leaps and falls on the floor and makes decisive, springing, almost balletic movements. He might sing an open-ended, non-repeating, monk-like chant, or play a single musical phrase in a tight lock, which is what he does on track six of Watashi Dake?, “I Can’t Do It Properly.” The super-charged, four-note row rolls over and over; he is intoning the words of the title, and adds at the end: “. . . imitating myself, imitating myself.”

In the mid-1990s, the English academic Alan Cummings, who has done the best elucidation of Haino for Western audiences, asked him what he does to prepare for a concert. Here was the reply:

Before I make any sounds, first of all I breathe in all the air in the performing space. Most performers feed off the audience, but I’m conscious of entering into a relationship with the actual air in the place, even before the audience has arrived. After breathing in all the air, when I breathe out again I want to engulf the audience in that air. And then on top of that, I want to return the air to its original state again. When I breathe in all that air and engulf the audience in it, it feels like I have become god. That in itself would be blasphemy, which is why I then return the air to its original state.

That answer is preposterous, but perhaps only as preposterous as any art ever is. It is also accurate in that it contains Haino’s big paradox: his work remains absolute, confrontational, not beholden to anything, yet also brings intense respect and sensitivity for the situation and discipline of performance.

Haino was in his late twenties at the time of Watashi Dake? The record initially came out in an edition of a thousand copies. I, and many others I knew, didn’t learn about him at all until more than a decade later, through mentions of his band Fushitsusha in Forced Exposure in the early 1990s—a publication whose writers made an absurdist game out of knowing every arcane cultural movement in twentieth-century music. But about Haino they knew comparatively little, and this was strange, because by then he’d already been around for twenty years. His history traced back to the band Lost Aaraaff and the Japanese early-1970s free-rock scene, but at the time hardly anyone in the West understood what that even meant.

Fushitsusha is sort of an abstruse analogue to Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys: Haino with a Gibson SG and Marshall amps and foot pedals for distortion and reverb, leading an acid-rock power trio while not at all caring about the form of rock per se. (Fushitsusha still exists; it will play two nights at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn this month, booked by the curatorial organization Blank Forms, as part of the foundation’s ongoing Grand Ole Opera exhibition.) But Haino’s great strength all along has been solo performances such as what you hear on Watashi Dake?

This is not the only Haino solo record that begins with a scream. (See The Caution Appears.) Haino’s art tends toward the nonnegotiable or mystical—“revolution and miracles,” as he told Cummings—which should mean that it is hard to understand. But this record is not so hard to understand. In his own way he is addressing the same problem that fascinated Agnes Martin, Lorca, Cézanne, Bacon, Beckett, and late John Coltrane: how to avoid cliché in constructing a true response, how to get around the known or pre-sequenced, how to avoid imitation of others—or even worse, of yourself—and make the energy of the artistic act beam from the art directly into the beholder. Above all, I am convinced that what is going on with Haino, then and still, is a drive toward an idea of virtuosity that—perhaps strangely—is not about traditional instrumental ability, and not even really about ideas. It is about gesture: a scream, or a silence, or a sudden lunge, which says all there is to know at that moment. I picture one of Haino’s foot pedals saying GESTURE on it. It is pressed down completely all the time.

Ben Ratliff is the author of four books, including Every Song Ever.