Andrea K. Scott

Andrea K. Scott

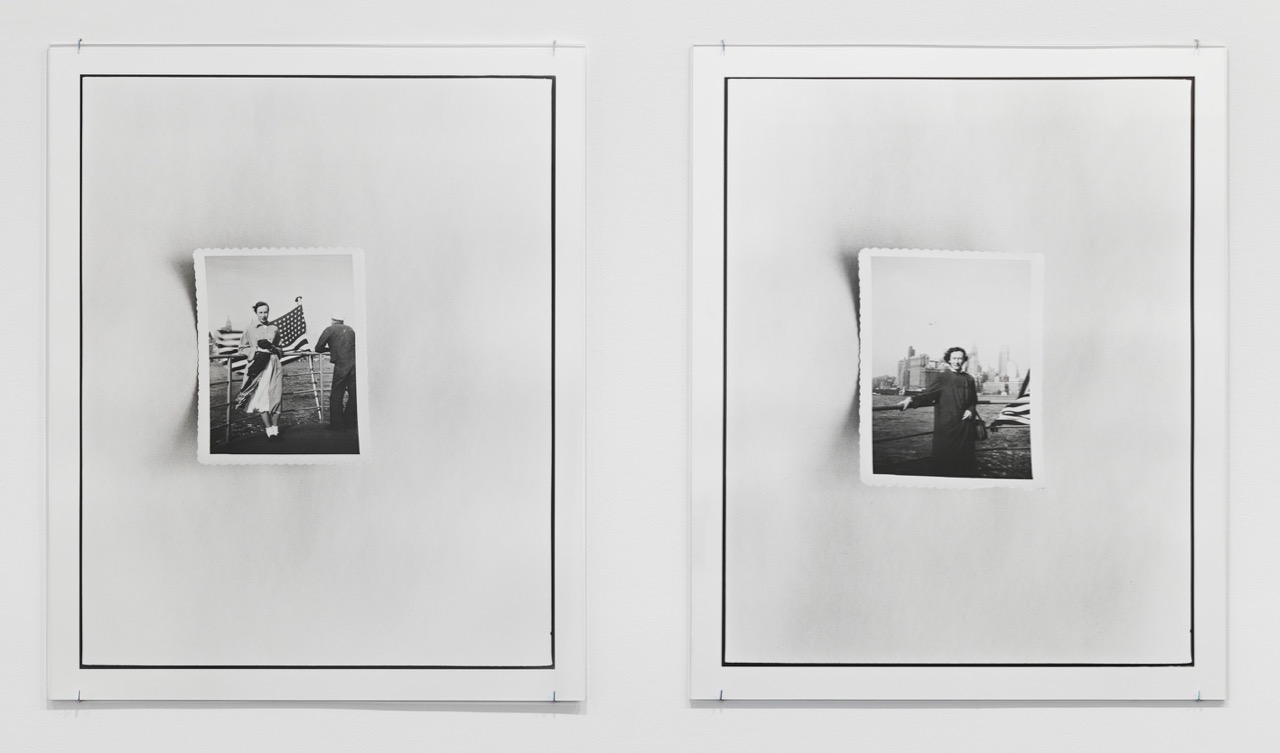

Zoe Leonard, Warsaw 1943, 2016. 2 pigment prints, 11 3/4 × 9 1/4 inches each. Ed. 2/6 + 2 AP. Image courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Zoe Leonard, In the Wake, Hauser & Wirth, 32 E. Sixty-Ninth Street, New York City, through October 22

• • •

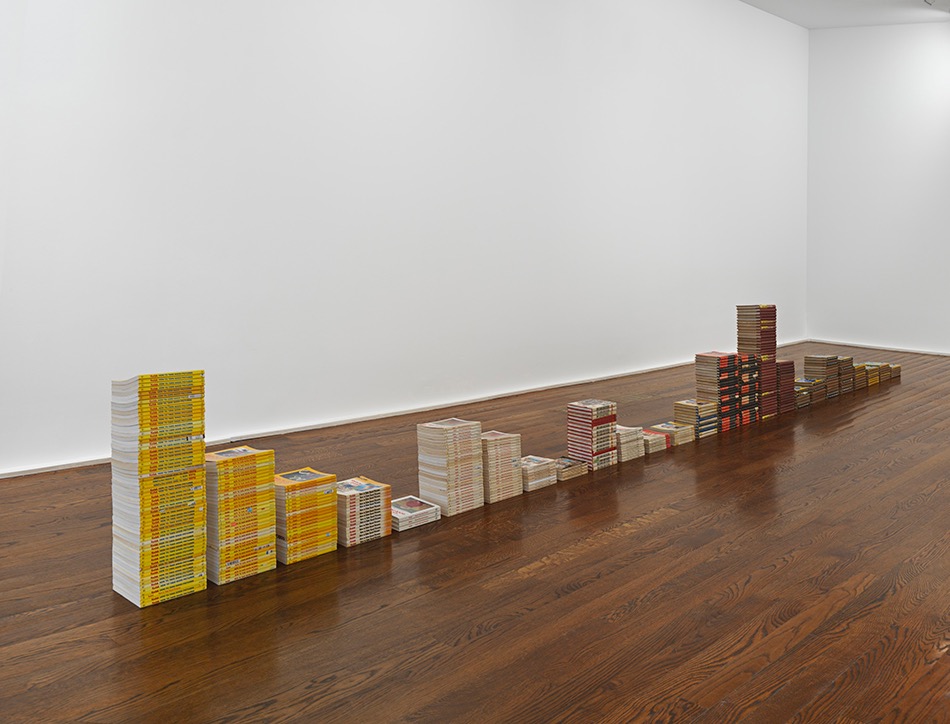

What is photography? The first piece viewers encounter in Zoe Leonard’s fiercely intelligent, deeply felt show at Hauser & Wirth, the mid-career artist’s debut at the gallery, answers the question with a stack of forty-six vintage copies of the same book: This Is Photography. The sculpture is a triple entendre: a love letter to print in the era of digital, a nod to the photograph’s status as a perpetual copy, and a conceptualist's punchline. Forget a picture being worth a thousand words, Leonard compresses the whole medium into three.

In the context of art, photography is a delivery system for slippery ideas about reality and representation. Also, these days, about obsolescence—when every digital phone comes equipped with a camera, who lays claim to the title “photographer”? In the context of family, photography is a mirror, which the past holds up to the present. The soul of Leonard’s show is a cache of old snapshots, some of which she found in a suitcase while cleaning out her mother’s house, following her death in 2008. (Uncannily, in 2002, Leonard conceived an ongoing sculpture, now owned by the Guggenheim: a row of second-hand suitcases, one for every year of her life. It remains unfinished as long as she lives.)

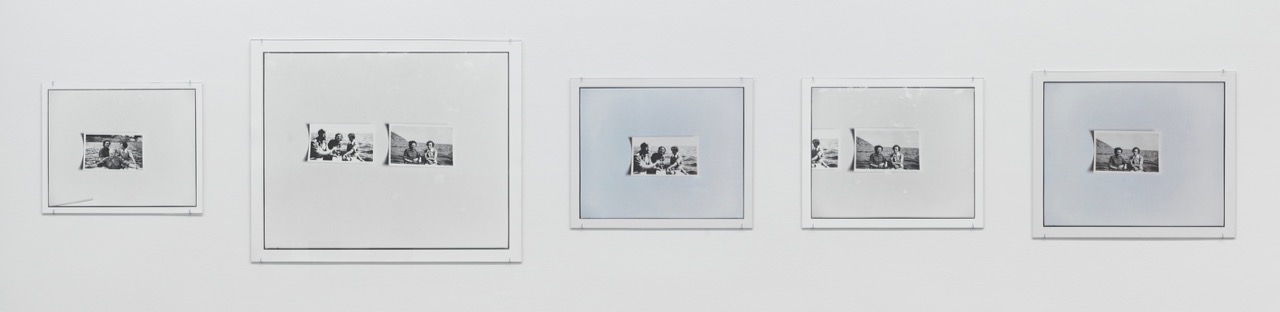

Leonard’s discovery fleshed out a story she already knew, about a mother and daughter—her mother and grandmother (a fighter in the Polish resistance), who lived in Warsaw, until the Soviet occupation forced them out, at the tail end of the Second World War. She photographed the pictures and has installed the second-generation results in diptychs, triptychs, and groups of four or five on the gallery walls. Each series is made up of variations on the same image; cropped, enlarged, reframed, and then seen side-by-side, they remind us that every experience has more than one version. Memory, like photography, can be an unreliable narrator. Some of the original pictures appear curled by time; others exist only as fragments. In one selection of four spectral images, the figure of Leonard’s mother is entirely obscured by the camera’s flash, disappearing into the light.

Zoe Leonard, Italy 1946, 2016. 2 C-prints and 3 gelatin silver prints, 10 7/8 × 13 3/8 inches, 18 1/2 × 22 9/16 inches, 12 1/2 × 15 1/4 inches, 12 1/2 × 15 1/8 inches, 13 7/8 × 16 7/8 inches. Ed. 2/6 + 2 AP. Image courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

For more than a decade, Leonard’s mother and grandmother remained stateless: we see the pair in locations identified by the works’ titles: Warsaw 1943, DP Camp (shorthand for “displaced persons”), London, Italy 1946, and, in one untitled picture, on a sidewalk in the kind of in-between, nondescript landscape that has preoccupied Leonard’s camera for years. (The third floor of the gallery is devoted to Leonard’s new series documenting flocks of pigeons in flight, at once banal and sublime.) The United States was the women’s final destination. When New York Harbor appears, it is behind a windblown American flag, in one instance, and with the Statue of Liberty in the distance, in another. (In one of those beautiful accidents to be filed under “truth, stranger than fiction,” Leonard was born in a New York village named Liberty.) We never learn the artist’s grandmother’s name in the show, but her mother, Misia, is occasionally identified. In a group of five pigment prints, titled Crossing the Equator, Misia gazes into a camera’s viewfinder, just as her own daughter would, decades later.

Close viewers of Leonard’s work over the years may recall meeting Misia and her mother before. The first image reproduced in the artist’s 2008 monograph, Zoe Leonard: Photographs, is a portrait of the back of her grandmother’s head, in the front seat of a car; printed on the reverse side of the same page is a portrait of Leonard’s mother, facing forward in the back seat. The pictures were taken in 1979, when Leonard was eighteen years old. She would wait another eighteen years to print them, in 1997.

Zoe Leonard, How to Make Good Pictures, 2016. 429 books, 25 1/4 × 6 1/8 × 248 3/4 inches. Image courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Leonard’s deep dive into the personal at Hauser & Wirth, at once tender and rigorous, is as much about her relationship to the medium of photography as it is about family. The works in the show run a gamut of analog processes and formats threatened with extinction by digital dominance: pigment prints, C-prints, gelatin silver prints, and, perhaps especially, books. Her stack sculpture This Is Photography is joined elsewhere in the show by several others, including a glowing orange pile of vintage how-to photography books titled Dealing with Difficult Situations, installed in the same room as the occluded pictures of Leonard’s mother. The most extensive stack piece at Hauser & Wirth is How to Make Good Pictures, an over-twenty-foot-long row of volumes published from the 1930s through the 1990s (the varying heights of its stacks lend the piece the silhouette of a skyline). The question of how to make good pictures—or, more aptly, of how to post them—is, of course, an obsession of the Instagram age. But Leonard’s reflection on her family’s odyssey from Warsaw to New York argues for a more thoughtful reflection on the construction of self than Throwback Thursdays and selfie-clogged feeds can afford.

In the Wake, the show’s deftly poetic title, refers, on a literal level, to the churning water trailed by a ship, evoking the ocean crossings of countless displaced persons, from Jews fleeing Hitler and Stalin in the mid-twentieth century, to the twenty million people currently without a home—the worst refugee crisis in global history. Crucially, a wake is also a vigil—a remembrance, not unlike a picture. There is no doubt that Leonard intends her private story about the mother she lost—and the history that loss then returned to her—to resonate with current events. Political activism has been at the heart of her art since the 1980s, and her work with ACT UP and the feminist collective fierce pussy. Leonard’s eloquent tale of a parent and child adrift for years before sailing into New York Harbor is antivenom to the pernicious political rhetoric of the likes of Donald Trump that denies a fundamental American truth: in the wake of the genocide of too many native people to count, we all trace our roots to an immigrant.

Zoe Leonard, New York Harbor I, 2016. 2 gelatin silver prints, 21 × 17 1/8 inches each. Ed. 2/6 + 2 AP. Image courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Andrea K. Scott is a writer and editor on the staff of The New Yorker magazine, where she has written on subjects ranging from a profile of the sculptor Sarah Sze to an appreciation of the downtown art maven Lia Gangitano. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times, T Magazine, W, Parkett, Cabinet, and frieze, as well as in monographs and museum catalogues. In 2014, she was the recipient of the Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.