Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

Welcome to excess: Heiner Goebbels takes over an armory to confront the twentieth century.

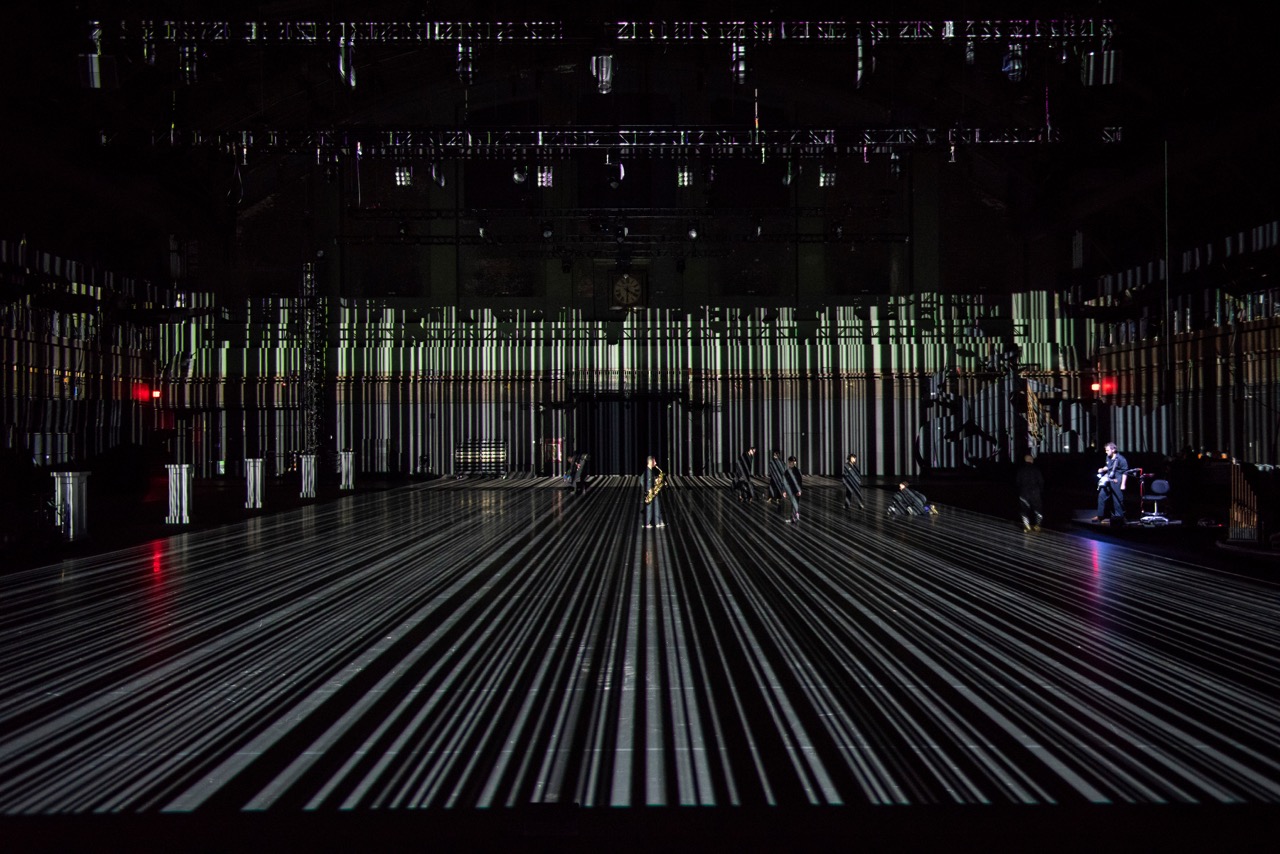

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

Everything that happened and would happen, directed by Heiner Goebbels, the Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue, New York City, through June 9, 2019

• • •

Despite his love of abstraction, Heiner Goebbels—international superstar director/composer, winner of the Ibsen Award, lion of the German stage—does sometimes create conventional theatrical productions. A few years ago, for example, he directed Louis Andriessen’s minimalist opera De Materie, and while it involved moonlike zeppelin-drones flying above an actual flock of sheep, his production still functioned as an illustration of the work at hand. Andriessen’s opera is about the invention of various paradigmatic technologies, so Goebbels showed us the contrast between the machine world and the animal one. It was a metaphor you could understand, anyway.

Often, though, he works . . . beyond the track. In a way that was once familiar from blockbuster directors like Robert Wilson (in Einstein on the Beach, for instance), Goebbels uses the stage as a place where meaning and mise-en-scène detach and reorient. People are treated like objects, and objects dance. The set, basically, is alive.

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

Everything that happened and would happen is one such trip—there is text, certainly, but the illustration-connection has been broken. Menacing shapes unfold and then get tidied away before your brain can quite parse them; an atonal musical landscape lurches and roils beneath us; frequently a person reads snippets from Patrik Ouředník’s 2001 stream-of-consciousness history Europeana, or a recent piece of news footage rolls. Sometimes it becomes a little glib (Europeana is written in a deliberately naïve voice), but then a coil of smoke will stun you with its beauty. Considering that Everything was commissioned in the UK as a memorial to WWI, and considering the production’s size, it insists on resisting monumentality. The High Modernists Gertrude Stein and John Cage are still Goebbels’s primary touchstones, which means that their trickster lightness (her love of the present moment, his dedication to chance) runs through his work like a silver thread.

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

The Park Avenue Armory is a vast hangar nearly as long as a city block. Along the edges of the football field–size playing space, Goebbels and his codirector Michael Morris of Artangel have placed five instrumentalists, isolated and lit like stations of the cross. Percussionist Camille Émaille stands in a nest of drums and gongs; saxophonist Gianni Gebbia either sits or—in one astonishing moment—glides slowly across the stage as a trompe l’oeil projection effect makes the floor seem to turn into a conveyer belt. (René Liebert did the video design.) Cécile Lartigau perches at her ondes martenot, a theremin-like instrument made of a tiny piano wired up to a suitcase-sized lute-body; Léo Maurel settles down among the props and pipes of his sprawling DIY organ; and Nicolas Perrin jams on a modified guitar, sending odd pings and burps and growls through the floorboards.

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

The music, a hybrid of composition and improvisation, sometimes recalls an air-raid siren, or a horror-movie score, or construction noise. At all times—loud or soft—it sounds like an emergency. There is plenty of preshow chaos: random props lying on the ground, unrolled scenic drops and the tubes that once held them, gigantic false footlights, and, for some reason, a golden sun with a single wavering ray in the far black distance. The music and much of the hustle and bustle begin before we take our seats, so the difference between preshow and show is deliberately vague. Eventually we realize things have begun. “In the Golden Age,” a man says, reading from a book, “people were racists but didn’t know it yet.” He goes on to tell us about the way colonizers once put Zulus in zoos, and someone wheels him away in a laundry hamper.

The movements themselves are fashioned from theatrical mechanics: the dancer-actors are in technician coveralls, and during our two hours with them, we’re often watching the eleven-member ensemble tying scenic drops onto trusses before the wings are hoisted into the air (their unpainted sides facing us) or slowly folding soft goods. Instead of blackouts, Goebbels projects videos of No Comment sequences from Euronews—long shots from Vilnius or Venice or Dhaka—as though we’re seeing the TV left playing in the greenroom.

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

Visual echoes of other artworks are everywhere. One scene is just the slow advance of huge black oblongs out of the dark, like a 2001 homage; another involves the dancers rolling fake boulders back and forth with huge rakes, an image of Sisyphus as we hear about Buchenwald. There’s a triumphant, blessedly wordless sequence at the end, in which puffs of smoke and piles of heaped-up junk turn into a stage-wide sculpture that (I know this sounds crazy) looks like an object-theater version of The Raft of the Medusa. According to our program, the set pieces—which include a painting of a Blake-ian monster with an open maw, multiple white plinths, and a series of massive coffin boxes—are detritus from another Goebbels production: his 2012 staging of Cage’s Europeras, which was a glossy spectacle in Bochum, Germany, at the Ruhrtriennale. Everything that happened’s text, which is read in a number of languages, is about the front-facing parts of history—Empires and Wars and Presidents and the Millennium Bug—but the images are all verso. The twentieth century was a nightmare, certainly, but at least we’re behind the scenes.

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

When the 2018 production premiered in Manchester, it ran three hours. When the Armory program was being printed, it was apparently two and a half. But by the time it performed Monday night, it had been shaved to just over two hours—a concession, perhaps, to the New York attention span. For some, the intermissionless evening was still too tough: a number of people slipped out during the show. Certainly, there were sections when your mind wandered away from the piece, and the effortful playfulness—one can have too much hamper rolling—could wear thin. In sections, Goebbels has borrowed Ouředník’s wry tone, which is not entirely successful. We hear a line about Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” book: “But lots of people did not know the theory and continued to make history as if nothing had happened.” Ho ho! Too droll.

Everything that happened and would happen. Photo: Stephanie Berger. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

What is successful, as always with Goebbels, is the muchness. There are too many things to take in with the eye, and the pressure to do it, the enforced sensorial gluttony, has its own velocity and excitement. Everything is a lesson in surfeit, both at a level of stimulus—by the end I felt like a toddler after too much sugar—and life. This is what Goebbels made with the refuse left after another show, and you feel he could have made a dozen more. The end of the twentieth century has left us with a great deal of trash. But this is not, Goebbels tells us, the same thing as being left empty-handed.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, Art in America, Artforum, and American Theatre.