Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

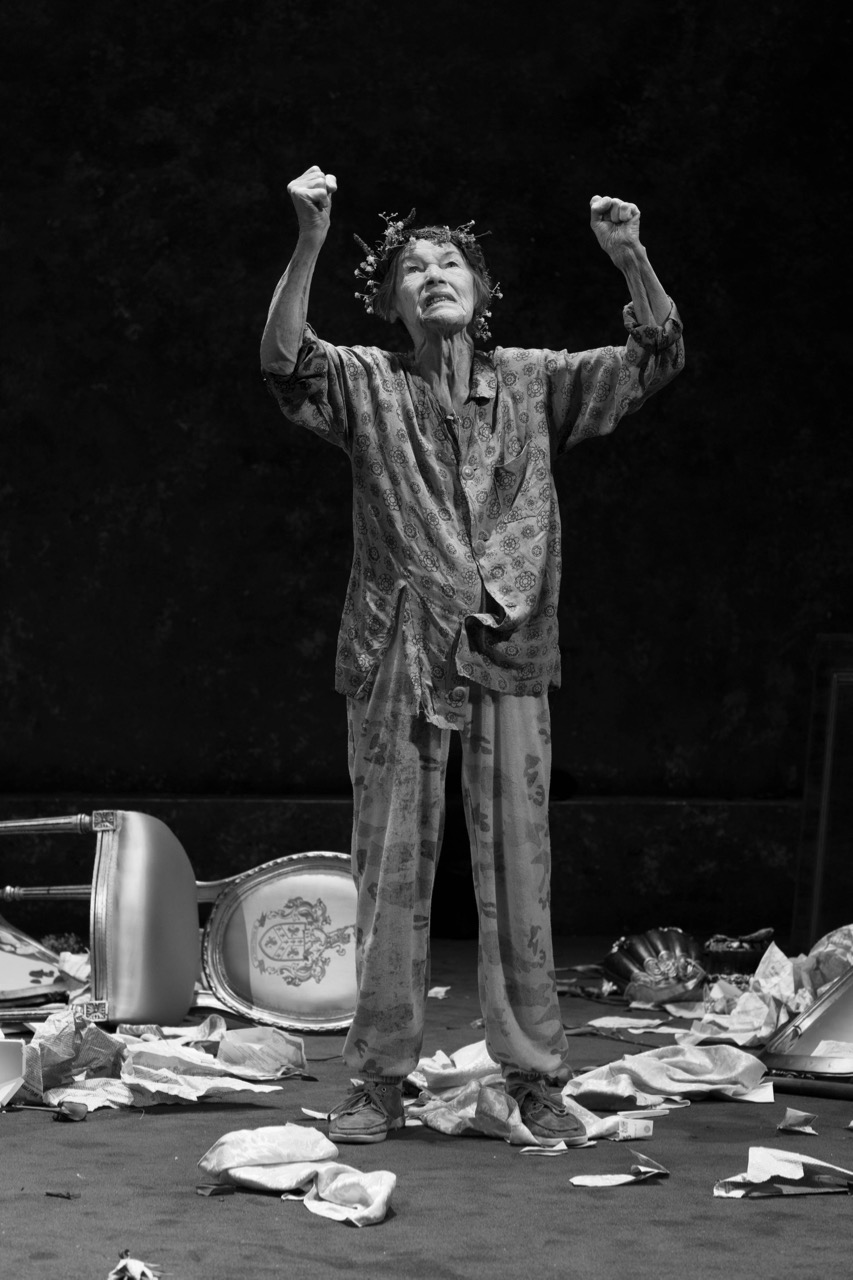

This way madness lies: Glenda Jackson stars in an errant

Broadway production.

Glenda Jackson as King Lear, with cast. © Brigitte Lacombe.

King Lear, by William Shakespeare, the Cort Theatre, 138 West Forty-Eighth Street, New York City, through July 7, 2019

• • •

King Lear is one of art’s great contradictions. It’s Shakespeare’s pinnacle work, full of painful wisdom and mysterious terror. The poetry is unsurpassed: it sometimes seems too big to have been written by a man; some parts feel as though they’ve been written by the wind and rain. But as a play that actually has to be acted on stage, it’s rather . . . broken. In 1606, Shakespeare was figuring out how to insert a B-plot into his tragedy, and he muffed it. Characters disappear; plot strands snarl; the comedy has aged like a bad avocado. It may be provocative to think about the Fool’s jester character (you can eke a hundred dissertations out of the Fool as an avant-absurdist prototype), but the gag about two halves of an egg is never funny. To quote a certain king: never, never, never.

The play is also a trap, one baited with a plum. Everybody (old, white, and male) has taken a run at being Lear: in New York’s recent memory alone, we’ve seen Kevin Kline (2007), Ian McKellen (2007), Derek Jacobi (2011), Sam Waterston (2011), John Lithgow (2014), Michael Pennington (2014), Frank Langella (2014), and Antony Sher (2018). The role is the laurel placed triumphantly on a career. Yet—the part must not be played with pride. Lear un-kings himself in his very first line. He surrenders the crown, divides his kingdom, places himself under the boots of his thuggish daughters Goneril and Regan, goes insane, and then—because gods and playwrights are cruel—returns to sanity so that he can die in excruciating lucidity. He confronts what it is to be “bare, unaccommodated man,” and an actor playing him must undergo Lear’s dismantling. The headline speeches aren’t occasions for chest-thumping oratory. Play him as a badass, and you’ve missed him completely.

Which brings us to Glenda Jackson, who now bites into Lear on Broadway. She won a Tony last year for Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women, and she is now an adored icon for her uncompromising steeliness. Jackson seems as fierce as a cornered fox—when she’s receiving awards. When she’s playing a role, she’s ten times as frightening.

Glenda Jackson as King Lear. © Brigitte Lacombe.

This is actually the second time in Jackson’s just-revived acting career (she served as a minister of parliament in the UK during a twenty-three-year break) that the tiny eighty-two-year-old has taken on the mad king. In 2016, she played him at the Old Vic in London, and rumors buzzed about that Lear traveling to New York. Instead, Jackson has been plucked out and replanted (by glitz-wrangling producer Scott Rudin) in a new production led by director Sam Gold. Since Gold’s star-in-a-Bard credentials includes Oscar Isaac’s Hamlet, you’d assume he would be unfazed, but here the director’s hand seems unsteady: the show happens around Jackson rather than to her. She’s short and sharp as a nail driven into the stage floor, and Gold’s production cannot shake her. In act 1, her Lear is angry, defiant, sour, rigid. And her act 5 Lear—jaw still clenched tight enough to crack a nut—is a copy of the first. The famous ferocity, it turns out, doesn’t always modulate.

Gold is, for his part, trying like blazes to make the show his own. In fact, Miriam Buether’s set has turned the Cort Theatre stage into a gold-leafed box, complete with a mirrored gold ceiling—one part Russian oligarch’s dining room, one part Trump’s toilet. It’s literally a Gold production. Branding!

Elizabeth Marvel as Goneril in King Lear. © Brigitte Lacombe.

Everyone wears modern dress; swords become guns. A few behaviors have been updated too: Goneril (Elizabeth Marvel) scrambles in and out of her underwear for quickies with Edmund (Pedro Pascal), and the lackey Oswald (Matthew Maher) whines his lines in a nasal California sing-song. Russell Harvard (who is deaf) plays Lear’s eye-gouging son-in-law Cornwall, and his American Sign Language interpreter has been cleverly integrated into the action. All four of these actors have found ways to meld the Keeping Up with the Lear-dashians surroundings with their vivid, if isolated, portraits. Those who are trying to play it serious and by-the-book (Jayne Houdyshell’s heartbroken, murmuring Gloucester, John Douglas Thompson’s loyal Kent) fade in the rumpus.

Russell Harvard as Cornwall and Aisling O’Sullivan as Regan in King Lear. © Brigitte Lacombe.

And the rumpus is often very loud. If it weren’t such a crazy notion, I’d guess that there was a kind of war going on between director and star—an attempt at subversion by both. Jackson may be ignoring the production all around her, but Gold has a weapon up his sleeve: a string quartet, which sits onstage, playing an original Philip Glass score. The music is always intrusive, always destructive. A violin’s little wooden body has almost exactly Jackson’s volume and timbre, so when the instrument plays, her voice is drowned. During the storm scene, when Lear has to face the elements and lose his mind in earnest, the torturously irritating ee-er-ee-er underscoring abrades Jackson’s epiphanic monologue into noise. By the time a herald refers to the chamber quartet, nonsensically, as trumpets sounding—“Again!” the poor guy cries, while Glass’s neoclassical muzak plays without break—the play has turned risible.

Glenda Jackson as King Lear. © Brigitte Lacombe.

But whatever the distractions, we’re there for Lear. Does it mean something that he’s not being played by a man? It doesn’t seem to. Jackson is performing Lear as a distilled essence—fury incarnate—rather than as a human being. Her lines can sound like elocution demonstrations, complete with rolling r’s. “Why should a dog, a horse, a rrrrrrrrat have life / And thou no breath at all?” she booms, as her favorite daughter, the rebel Cordelia (Ruth Wilson), flops dead onto the floor via a descending noose. At this point, Lear is four lines from his own death, supposedly overtaxed in body and brain. Yet Jackson is still standing, growling majestically and brandishing her fist. She’s a refusenik to the end.

There is, though, one instant when the independent gears of Jackson’s performance and the adjacent production do click and turn together.

Ruth Wilson as the Fool, with cast in King Lear. © Brigitte Lacombe.

Wilson plays both Cordelia and the Fool (there’s a much disagreed-about line in the play’s last moments that suggests this double-casting). At first, her Cordelia seems stunned and sullen, and her Chaplinesque Fool is as opaque and unamusing and effortful as every Fool I’ve ever seen. But then, after a swift exile, Cordelia returns. In act 4, the outcast finally meets her father on very different footing—after her abuse and dismissal at his hands, now she arrives at the head of an army, while Lear is dazed and uncertain. Lear apologizes to her, then to the attendants. “I fear I am not in my perfect mind,” he says.

Ruth Wilson as Cordelia in King Lear. © Brigitte Lacombe.

It’s appropriate enough, I suppose, that the only one who can summon Lear into humanity is Cordelia. Wilson must have some magic in her, because for this one scene, Jackson conjures up Lear’s vulnerability: her hand rises to make some gesture, but she forgets it—the hand hovers in the air for a moment. She curls up in a wheelchair; she is suddenly shell-small. Then the two women kneel and look into each other’s face, and in this noisy, sometimes silly, often infuriating production there’s a moment of deep understanding and quiet. The storm stills, just as Shakespeare said it would, before it rages on.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, Art in America, Artforum, and American Theatre.