Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

Maxwell’s new play Samara lights out for the metaphysical West.

Matthew Korahais and Modesto Flako Jiménez in Samara. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Samara, by Richard Maxwell, A.R.T./New York Theatres, 502 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through May 7, 2017

• • •

For three decades, the director-playwright Richard Maxwell has been pursuing a form of radical aesthetic subtraction. Show after show, he experiments with draining away what we often consider central to theatrical performance—the art of pretending itself. His company, the New York City Players, includes both non-actors and actors, with the awkward anti-technique of the first serving as model for the latter. Some love Maxwell’s work (it has a droning, hypnotic quality), some hate it (see prior explanation). Indisputably, though, he has changed the theater, coaxing it to include a wider range of possibility. Theatermakers often cite Maxwell’s influence: deadpan performance can be hugely persuasive.

Maxwell has been easy for critics to write about—we said “affectless” and dusted our hands—though his simplicity is trickier than it looks. He ushered in an era of deliberate “badness” in the theater’s avant-garde, but he works with actors (Tory Vazquez, Jim Fletcher, Gary Wilmes) who are actually enormously skilled. His pieces’ power comes from performers repressing profound anxiety or emotion; that compression creates heat and danger. Put that leashed excitement into Maxwell’s violent plays—there’s usually a fight or murder—and the shows gain frightening energies. Little wonder he’s a darling of European audiences: his shows indulge hard-charging American fetishes (boxing, cowboys) and yet also contain an implicit, post-Brechtian, anti-individualist critique.

Maxwell’s new piece, Samara, is currently being produced by Soho Rep. But is it Maxwellian? Not exactly, though it’s trying to be. With Samara, Maxwell lifts his auteur’s hand away: for only the second time ever, his text is being directed by somebody else. Here Sarah Benson takes the helm. Benson, also Soho Rep’s artistic director, is known for changing her aesthetic to suit each play she directs, and she clearly believes a Maxwell script requires that Maxwellian style. So instead of trying to pursue her own vision in Samara, she has her own cast (a diverse crew of downtown-theater habitués) try to imitate the New York City Players anomie-affect. Despite some lovely moments, it’s a failed attempt: ironically, by pretending to be a Maxwell show, the production runs counter to his work’s ethos of—not pretending.

Steve Earle in Samara. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Samara is a metaphysical Western in the mold of early Sam Shepard. Its composer is the legendary Steve Earle, the country/folk singer-songwriter, and Benson (brilliantly) casts him as the narrator. Black buttoned vest, black jeans, a gray prospector’s beard—Earle is the Shepardian punk-Western idea embodied. As two musicians play his eerie Irish-inflected soundscape, he reads stage directions in his growling drawl; when he speaks, the production reaches an exquisitely focused poetry.

Paul Lazar and Jasper Newell in Samara. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

At the play’s start, we meet the youthful Messenger (Jasper Newell), who immediately runs afoul of his Supervisor (Roy Faudree). “Sirrah,” says the adolescent in stilted olden-timey talk, “I need to get paid. With whom do I speak?” Supervisor won’t pay up, but he’ll give the kid someone else’s IOU, so the Messenger heads out into the wild, trying to collect. He reaches his destination—it could be anywhere from Canada to some expressionist ur-frontier—where he duns the innkeeper Manan (Becca Blackwell). Manan’s dear companion the Drunk (Paul Lazar) has just severed their connection to civilization by tearing up their map, but after accidentally killing the Messenger (don’t do this), the two resolve to carry his body home to be buried—and they walk back out of the far reaches toward Samara, the city they’d left behind.

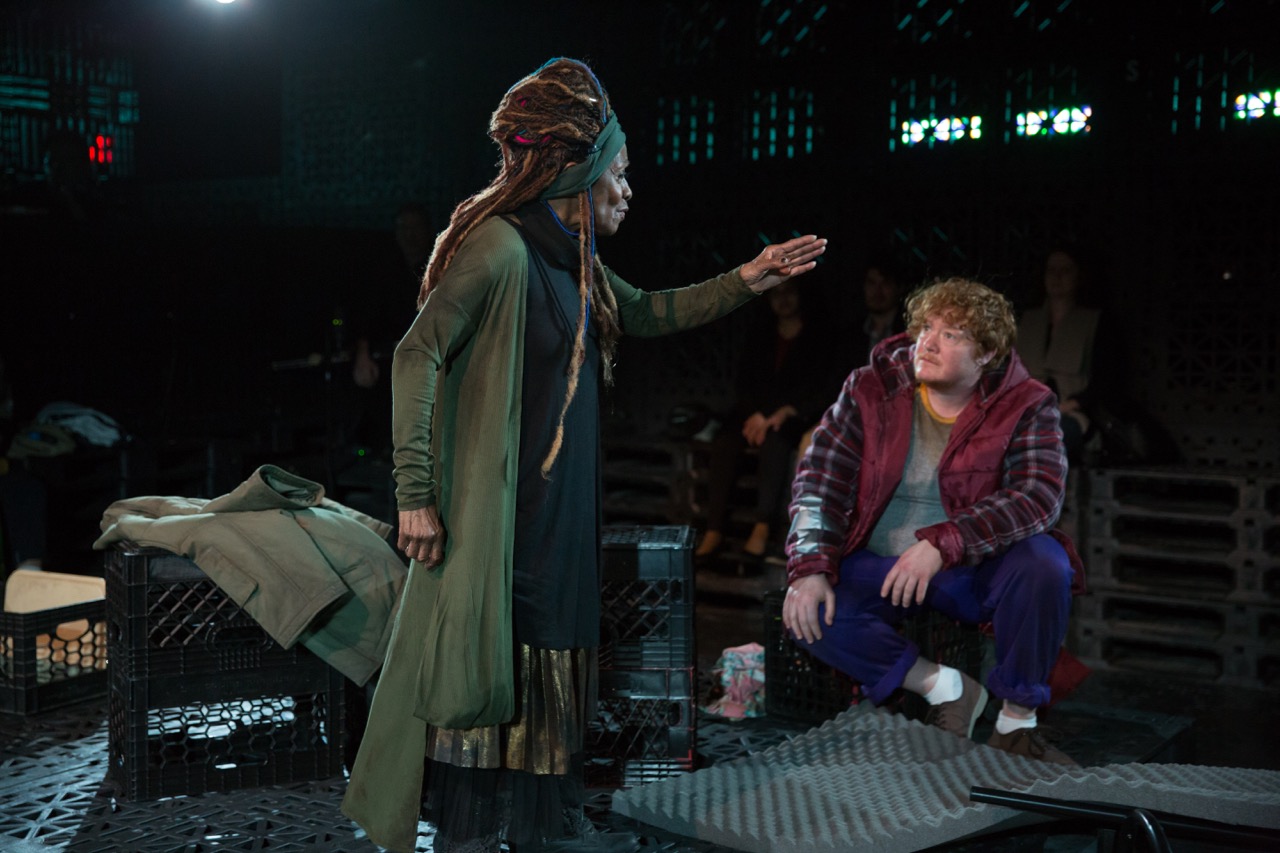

Vinie Burrows and Becca Blackwell in Samara. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

On their way, they meet other wanderers (including a Mother Courage–like Vinie Burrows) who turn out to be the Messenger’s own family. This is John Ford logic, in which a wilderness is empty except for those that you’ve done wrong. There’s a chance for resolution or revenge here, but the Western plot abruptly vanishes; its shotgun bluster drops away. The set—Louisa Thompson’s grim, black theater-in-the-round—erases itself in a white fog bank, then plunges into pitch darkness. (These gestures are Thompson and Benson’s way of honoring impossible instructions in the script: stage directions like “Platforms rise up and breathe” have to be interpreted somehow. Maxwell’s recent The Evening, which dissolved at the end into white smoke, may have been their inspiration.) In the dark, we hear Earle’s whiskey voice telling a story about a man’s nighttime hike with his small daughter. In this sweet, rueful monologue, man and child walk up a ridge as the path grows faint. They hear a wild horse, frightened and stumbling, crashing through the underbrush. “He’ll work his side of the street,” the man says, comforting the little girl. “And we’ll work ours.”

Samara is drenched in romanticism—complete with yearning for unsullied nature and landscapes reflecting the characters’ inner sturm. The intention is clearly to use a drained aesthetic to set it off. But while Blackwell, Lazar, Burrows, and Faudree are all usually marvelous performers, they seem lost here, roaming between conventional expressiveness and pseudo-deadpan. Benson can’t wrestle her ensemble or her stage compositions to gel into Maxwellian “no-style”; according to his own book on acting, it requires a quasi-Zen level of meditative discipline. Earle alone nails the tone—perhaps because, as a non-actor, he is compelling to watch while simply completing a task. (He mostly reads from a script; when he’s briefly off-book, you can see him clenching his hand behind his back in an agony of nerves.)

But while Earle’s performance hints at what a fully Maxwellian version could have been, I actually didn’t want Benson to tack closer to his influence. I wanted a production that seized the chance at seeing what Maxwell-as-writer could accomplish when fully abandoned to another creative mind. There’s a blurred, strange territory around what his flinty lyricism might become in another’s hands, but a director will need to escape his gravity well to find it. Is there a way to separate Maxwell’s writing from the style his company has already so fully mapped? The play itself—full of boundaries that change when you look at them—hints we should try. Samara couldn’t seem more timely: we need to discuss the ugliness in our American myths and our own current ambivalence about the Wild. But it asks for a production with more innovation, one forging its own aesthetic path out of those weird black hills. This one follows someone else’s trail, the surest method of losing your way.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, The Village Voice, TheatreForum, and diversalarums.com.