Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

Family, fatherhood, death: Jake Gyllenhaal and Tom Sturridge take to the stage in duo monologues.

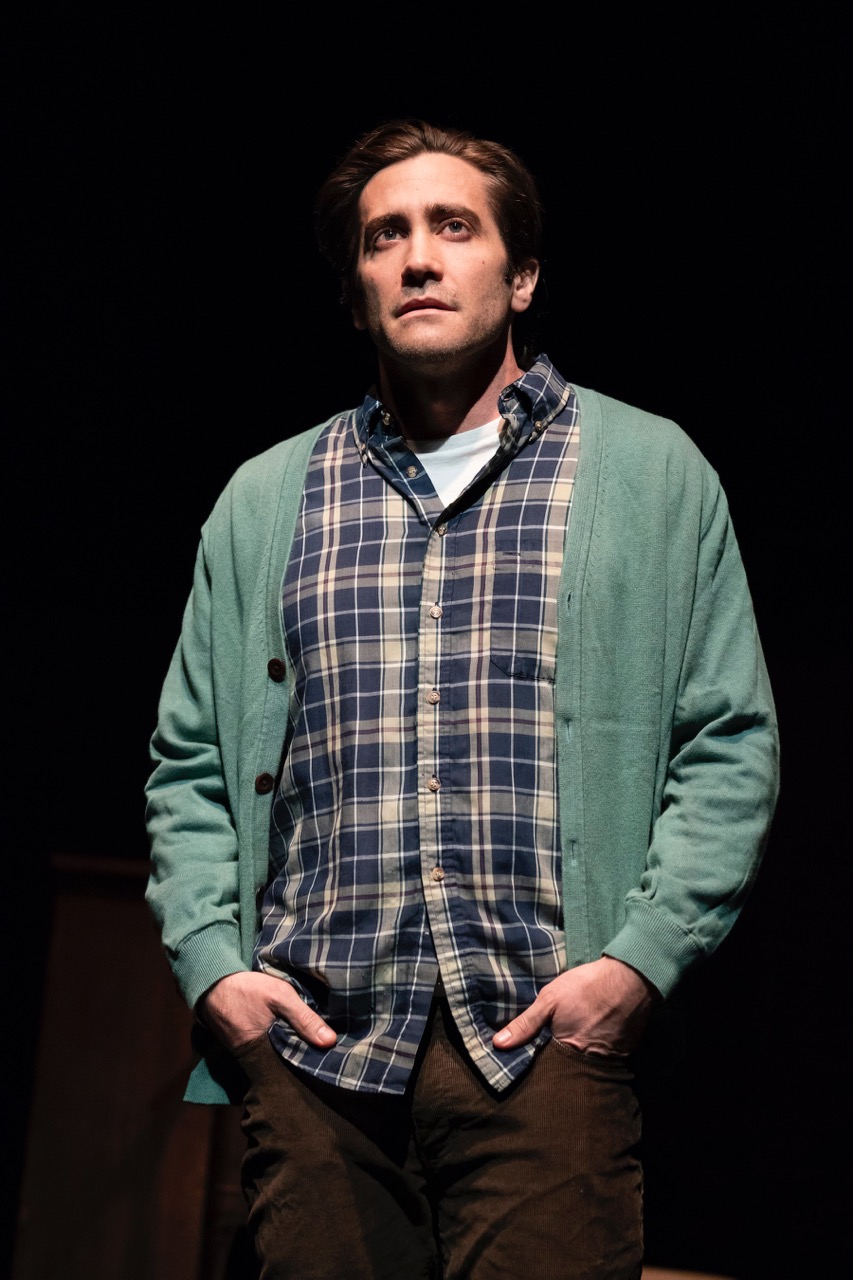

Jake Gyllenhaal as Abe in A Life. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Sea Wall / A Life, by Simon Stephens and Nick Payne, the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette Street, New York City, through March 31, 2019

• • •

If movie stars weren’t part of the package, would Sea Wall / A Life be at the Public Theater? It’s hard to imagine the Public—birthplace of Hair and Hamilton, heir to Joe Papp’s long legacy of promoting American playwriting—champing at the bit to stage two British monologues. One of the texts is eleven years old, for Papp’s sake, so we’re hardly talking about the form’s bleeding edge. But there we are, watching Tom Sturridge in Simon Stephens’s Sea Wall (2008) and then, after intermission, Jake Gyllenhaal in Nick Payne’s A Life (2019).

It’s an odd match: two sad stories done simply, yet with a marketing hook that’s pure movie-glitz. Clearly it’s the chance at proximity to charismatic stars that’s selling tickets here. Neither forty-five-minute solo play is quite enough to hold an evening by itself, and even when they’re performed together, there’s a distinct air of slightness. Go and you will find a great quantity of sentiment, a home truth, and a truly great performance. But despite that one piece of extraordinary acting, the tales themselves have a way of ebbing out of memory.

Tom Sturridge as Alex in Sea Wall. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Sea Wall is, in some ways, typical of 2000s-era monodrama. Alex (Sturridge) talks impressionistically about his life in glowing terms—lovely wife, lovely father-in-law, lovely little daughter all enjoying a vacation in the south of France—as we wait for the heavily telegraphed tragic shoe to drop.

When Stephens wrote it, the death of a child seemed like every writer’s favorite shortcut to tragedy. Remember David Lindsay-Abaire’s Rabbit Hole (2006), Jenny Schwartz’s God’s Ear (2007), and Bryony Lavery’s Frozen (1998)? In 2008, parental bereavement was theatrically on trend. Also typical: a certain on-the-noseness in the metaphor department. Alex is a photographer, and his story develops (ahem) from narrative confusion into brutal clarity. He and his father-in-law have frequent conversations about God—never a good sign. And halfway through his tale, Alex and his family go scuba diving, “and swimming there, with the sun, even as bright as it is above us . . . Even then the darkness of the fall that the wall in the sea reveals is as terrifying as anything I’ve seen.” This is not so much foreshadowing as it is fore-engulfing.

Yet the language is often beautiful, and the details sometimes glide lightly into place. Talking about his toddler daughter, Alex says, “She starts wearing cardigans and that’s me done for.” The line is a sketch; he doesn’t belabor the point. You can suffer through a lot of heavy-handedness for a line like that.

Tom Sturridge as Alex in Sea Wall. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Stephens originally wrote Sea Wall for Andrew Scott, and that actor’s effortless performance—a nearly supernatural piece of embodiment—set a high standard. (You can watch a filmed version on Vimeo.) Sturridge, though, is a mysterious stage creature. As was the case in another New York stage outing—the 2013 Broadway production of Lyle Kessler’s Orphans—Sturridge’s first few moments in front of you seem impossibly tic-ridden and affected. Slim and pale as an elf, with a trick of casting his head in a little nervous circle as he laughs, he gives the impression of being in constant motion. Even standing quite still in his army jacket and track suit bottoms, he shimmers with energy. The tortured way Sturridge speaks his first line, “She had us, both of us, absolutely round her finger,” already has the whole play in it—laughter, suppressed grief, a kind of feral weirdness that makes you wonder if Alex is all there.

Tom Sturridge as Alex in Sea Wall. Photo: Joan Marcus.

And, as in Orphans, that raised-by-wolves quality never goes away. We simply . . . adjust to it until it no longer seems like artifice. There is no gradual build with Sturridge. Instead of carrying the audience along an energetic arc, he starts at the apex and then stays there, vibrating. I’ve never seen another actor like him. Director Carrie Cracknell gives him a lot to do, so he eats, pours himself a glass of beer, climbs up a staircase to a high second acting level (Laura Jellinek designed the “no-set” set), knocks his belongings six feet down to the ground, looks at them meaningfully, etc. The added business doesn’t disrupt his performance, but Sturridge—bright as a phosphorus explosion—doesn’t need it. Why make him literally stand at the top of a wall? He seems so close to the precipice already.

Jake Gyllenhaal as Abe in A Life. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Back-to-back monologues—both performed by men in their thirties, both dealing with the same issues of family, fatherhood, and death—obviously encourage comparisons. These comparisons aren’t always flattering, though, since Sea Wall is (literally) a hard act to follow. Payne’s A Life, a rapid-cut double-portrait of the birth of a child and the death of a parent, has less grace and lyricism than Stephens’s more elegant work. And Gyllenhaal’s rather technical performance, which is often funny and nicely clear, seems mild and even calculated when coming so close behind Sturridge’s strange magic.

Payne has talked about writing A Life in response to his father’s death; its particulars are as realistic as diary entries. His alter-ego Abe (Gyllenhaal) tells us about his father’s heart attacks, which parallel the catastrophes that befell Payne’s father: the attempt to fit him with a pacemaker, the failures and grief that follow. Payne is a stylist—his Constellations, for instance, which starred Gyllenhaal when it was on Broadway in 2015, had a “multiple realities” gimmick in which scenes played with varying endings. Here, Payne has the speaker interlay his story about his father’s death with comic tales from his wife’s pregnancy and daughter’s babyhood. Abe toggles back and forth quickly enough that we’re disoriented. Do the white knuckles on the steering wheel belong to his mother or his wife? Is it the night of the birth? Or another, more awful night? The point is, of course, that there’s something similarly crushing about life’s doorway moments. And out of the story’s welter of details emerges one clear truth: “I don’t understand why we prepare so fucking wonderfully and elaborately for birth,” he rages, “and yet so appallingly and haphazardly for death.”

Jake Gyllenhaal as Abe in A Life. Photo: Joan Marcus.

As a cry, it’s from the heart. But as a play, it falls prey to cliché—gooey on a line-by-line measure (“She says: ‘You know he loved you, don’t you?’ ”) and narratively overfamiliar, with “dopey dad” stories that may have actually happened but sound reheated. Neither play stakes a long-term claim, but A Life—with so little novelty—vanishes even more quickly from memory. An informal poll showed a divide in the audience about the evening: those with recent bereavements were touched; those without one saw it as a bit . . . hokey. Solo performance of this type has so much air in it—it demands so comparatively little from us in terms of where to look, what story to believe—that it leaves a lot of time and mental energy for in-the-moment self-reflection. If you see yourself in Sea Wall / A Life, then it will feel like the parable is being delivered to you. For the rest, we’ll just have to wait. Loss comes to us all: it’s a tide that will always, eventually come in.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, Art in America, Artforum, and American Theatre.