Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

A chocolate dilemma: Renzo Martens brings his problematic art enterprise to the SculptureCenter.

Jérémie Mabiala reflecting on his work, 2015.

Congolese Plantation Workers Art League, SculptureCenter, 44–19 Purves Street, Long Island City, through March 27, 2017

• • •

At once an art-world provocateur and a proponent of social engagement, Renzo Martens has pursued a decade-long project in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that tends to be judged according to the Dutch artist’s humanitarian motives. Critic T.J. Demos, for example, has made a case for Martens’s work predicated on the alleged sincerity of his interventions. But no matter how good-hearted (or not) Martens may be, there is a potentially exploitative cast to his practice that is hard to dismiss in the name of art.

Installation view of the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League at the SculptureCenter. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

The latest manifestation of Martens’s conceptually knotty project is a series of chocolate sculptures made by a collective called the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise, CATPC for short). Debuting in 2015, the sculptures are now on view for the first time in the US at the SculptureCenter. But the exhibition isn’t really about these works, which likely wouldn’t be shown in a museum at all if it weren’t for the complex conceptual structure of which they are a part. The exhibition, in fact, seems to be more about that structure itself, which belongs not to the twelve to fourteen members of CATPC (all current or former plantation workers, many of them trained in woodworking), but to Martens, the semi-elusive conductor orchestrating the whole project.

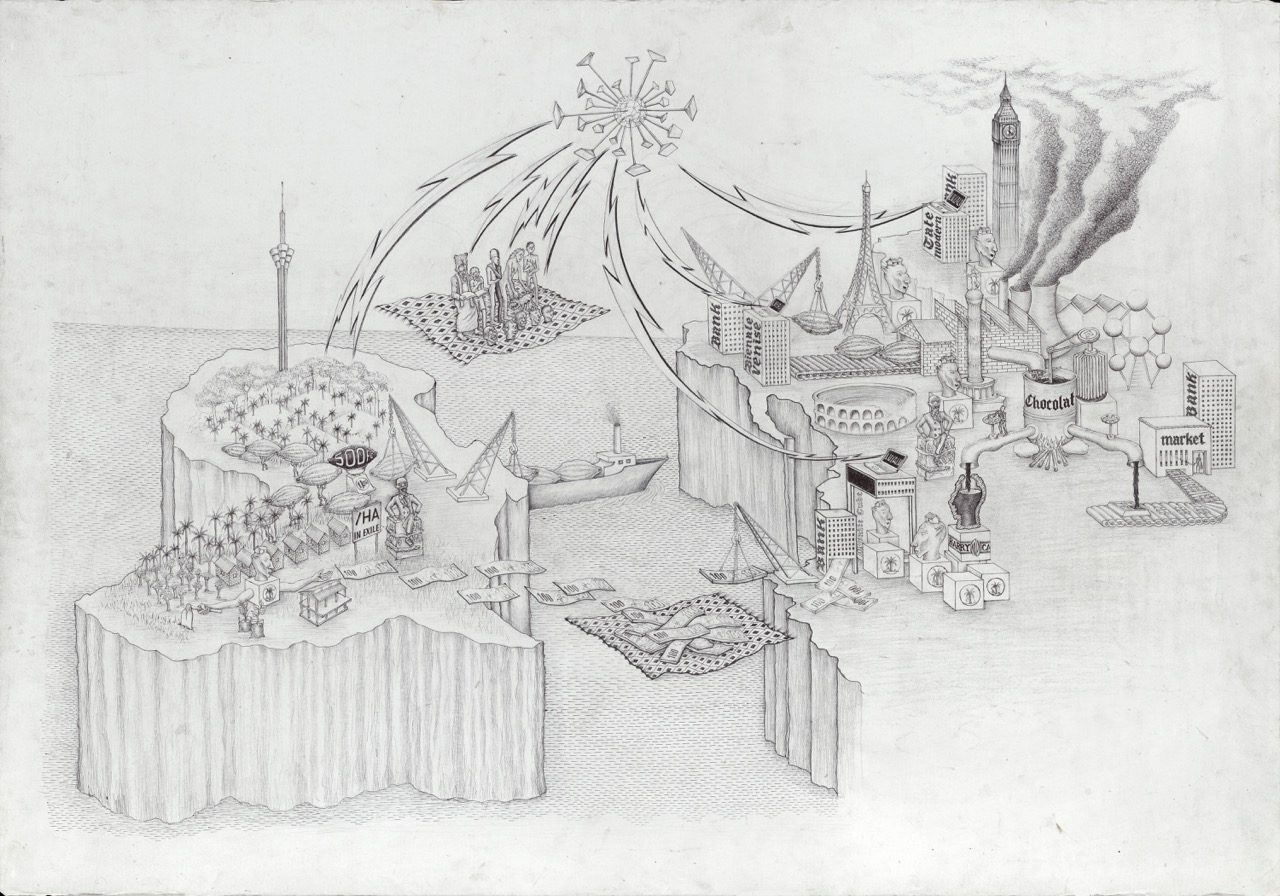

The objects on view do manage to command attention. CATPC member Thomas Leba’s sorrowful sculpture Poisonous Miracle (2015) depicts a nearly life-sized woman, her face contorted in pain as she reaches with long, attenuated arms toward a beastly chameleon biting her foot. Mbuku Kimpala’s unabashed Self portrait without Clothes (2014) is a bold, blurry nude figure with her legs splayed. Accompanying the chocolate portraits is a suite of ink-and-pencil drawings ranging from the humorous (Mao Kingunza’s portrayal of a foiled robbery) to the graphically violent (Irene Kanga’s brutal depiction of a rape).

Thomas Leba, Poisonous Miracle, 2015. Chocolate, 54.7 × 22.4 × 33.9 inches. Image courtesy CATPC, Galerie Fons Welters, and KOW. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Still, the works gain the bulk of their interest when situated in Martens’s elaborate network of production and dissemination. The artists first craft the sculptures in mud; they are then 3-D photographed, the files sent to Amsterdam, molds 3-D printed, and the final works cast in chocolate (often donated by the French-Belgian group Barry Callebaut, to underscore the radically violent colonial legacy that thrums at the core of the project). It must be noted that the question of decision-making and authorship within CATPC is unclear. Speaking at the press preview and an accompanying symposium, Martens was careful to distance himself from the collective’s work, and a recent New York Times article asserted that all decisions are made through a group vote among the participants. But a robust publication on CATPC (published in 2017 by Sternberg Press) attests that it was Martens who asked the group members to work in sculpture, generally, and portraiture in particular. It was also Martens and his administrative team who devised the system by which the sculptures are fabricated.

Cedrick Tamasala, Sans titre, 2016. Ink and graphite on paper. 39.4 × 27.6 inches. Image courtesy CATPC, Galerie Fons Welters, and KOW.

The chocolate sculptures (each cast in an edition of five, plus two artist proofs) are shown in galleries and museums internationally, where they are put on offer to collectors. The proceeds all go back to CATPC (Martens told me some 50,000 euros have been raised so far), and the collective votes on how to reinvest the funds. According to Martens and his collaborator, the high-profile environmental activist René Ngongo (now the president of CATPC), so far the members have chosen to buy back lands and create their own “postplantation” (of course, that nebulous language also belongs not to the artists/workers, but to Martens and Ngongo). And the project will soon grow even further, and quite dramatically—in spring 2017, a new OMA-designed exhibition space (which Martens insists, with key symbolic value, on calling a “white cube”) and research center will open in the town of Lusanga, on the site of a former Unilever plantation. The idea, Martens explained at the symposium, is to disrupt a neo-colonial economic cycle operating in the international art world, in which corporations relying on plantation labor fund cultural centers in the West. By creating the gallery and research center on the site of the plantation itself, the aim is to reverse the flow of capital back to the periphery.

Martens’s engagement in the DRC began with his at times unbearably cruel documentary, Episode III: Enjoy Poverty (2008)—an intentionally self-reflexive indictment of the ethics of aid work and conflict-zone journalism that propelled the artist to international art-world fame (and notoriety). Shot in 2004 and 2008, Enjoy Poverty follows Martens as he tries to convince a group of Congolese photographers to capitalize on what he argues is their greatest natural resource—their own poverty. He encourages them to compete with international journalists and take their own photos of cadavers, raped women, and starving children, and coaches them in how to capture the most harrowing images. But when it becomes clear the enterprise is doomed to fail, he advises that they learn to accept their deprivation and stop striving for anything more. Then he leaves.

Still from Renzo Martens, Episode III: Enjoy Poverty, 2008.

But not for long. Martens returned to Congo in 2012 to found the Institute for Human Activities on a plantation near Kinshasa, an arts institution that he billed as the cornerstone of a “gentrification program” meant to explore if art can be effectively instrumentalized to redress economic inequality. (Richard Florida of The Rise of the Creative Class was, indeed, a guiding light of the project.) CATPC was born out of the IHA’s activities, when in 2014, Martens invited Eléonore Hellio, Michel Ekeba, and Mega Mingiedi to lead a sculpture workshop with local plantation workers in Lusanga.

The many tentacles of Martens’s Congo project are highly effective at a number of things—inciting debate around crucial questions concerning cultural economies and asymmetric conditions of power, for example, and providing a boon for a very small, select group of people in Lusanga. To read the artists’ transcribed statements, it appears to be a transformative project for them, and a source of great pride and enrichment for their everyday lives. But at the same time, the criticisms that could be leveled against this multi-layered project are many: it appears to be a decidedly top-down approach to development; Martens’s role as a parachuting, white, Western do-gooder/master of ceremonies is ethically troubling; and replicating problematic systems and symbols (the recreation of the modernist white cube on a plantation being a prime example) in the service of critique may inevitably perpetuate the violence of those systems and symbols, rather than undermine them. There is, moreover, something akin to a colonial missionary zeal to the whole thing—Western experts bringing artistic knowledge to the poor, and Western experts then repackaging and exporting the fruits of cultural labor from the plantation back out for international consumption. And ultimately, to what extent is Martens using CATPC members themselves as raw material in a mainly discursive meta-project aimed at a Western audience, much as he did in Enjoy Poverty? Whether Martens is sincere here or not, several (potentially treacherous) ethical questions are left to linger.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns. From 2011–15, she was the chief curator of Townhouse, a nonprofit contemporary art space in Cairo, Egypt; she was also a founding editor of Mada Masr, Egypt’s premiere platform for independent, progressive journalism. She is a recipient of a 2016 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.