Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Fielding the hazards of art as activism.

Songs for Sabotage, installation view. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Songs for Sabotage, The New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through May 27, 2018

• • •

“The kids aren’t all right” could be an alternative title to the 2018 New Museum Triennial, Songs for Sabotage. The state of the youth is often used as a barometer for the health of society at large, and this presentation of twenty-six young artists tells us what we already know: things aren’t going too well. Gary Carrion-Murayari and Alex Gartenfeld’s densely theorized curatorial premise boils down to capitalism is bad, and the youth are fed up. In response, they are creating works that serve as “a call for action, an active engagement, and an interference in political and social structures urgently requiring them.”

This heavily charged moment of ideological, economic, and ecological crises can generate expectations for art to serve as activism. But what results from such a desire? Repurposing a term first coined by Adrian Piper, Negar Azimi’s 2011 essay “Good Intentions” invoked the notion of “easy listening art” to explore this question. Easy listening art doesn’t traffic in ambiguity. It emphatically checks all the boxes sanctioned by the progressive left, reflecting our ideals back to ourselves in a reassuringly digestible form, enabling us to believe that we are standing in solidarity and making our voices heard. And, thus, it resounds in an echo chamber. While seeming to agitate for change, ironically, this art actually relieves us of the burden of having to do anything at all, letting us bask in feel-good consensus.

I wasn’t surprised to find that Songs for Sabotage was riddled with this sort of Lite FM political gesture. Take, for instance, Peruvian artist Daniela Ortiz’s clumsy suite of small-scale maquettes of public sculptures to replace monuments to Christopher Columbus. On the shoulders of the oppressor our pain will weight (2018) features a red votive-candle-like form shooting up from a base supported on the backs of prostrate men. This land will never be fertile for having given birth to colonisers (2018) shows a triumphant mother with child standing amid the bloodied decapitated heads of her oppressors. The sum amounts to a series of one-liners ripped from the headlines; despite its violent imagery, this is not work that troubles, as the curators suggest, as much as it reaffirms the anti-colonialist position that most of us in the art world already hold. I’ve loved Ortiz’s work elsewhere, but the demands of a propagandistic reaction to current events drained this series of the nuance and biting humor that infused her earlier projects.

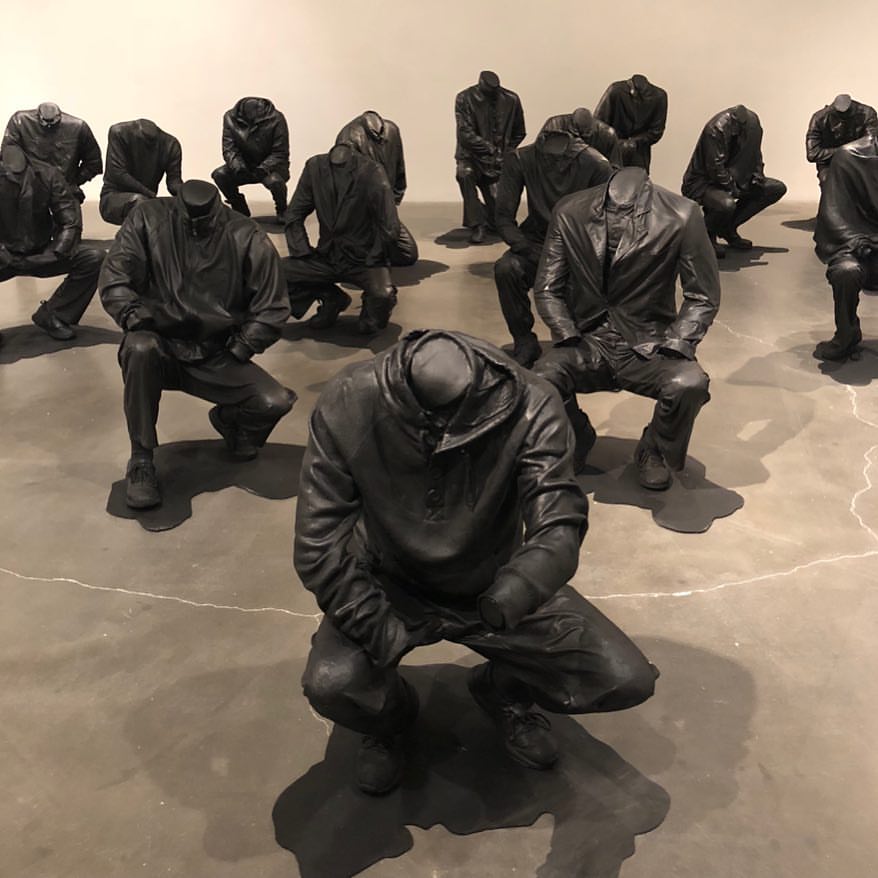

Haroon Gunn-Salie, Senzenina, 2018. Mixed-media installation.

South African Haroon Gunn-Salie’s Senzenina (2018) is another heavy-handed statement. The focal point of the third-floor gallery, the work consists of an imposing group of headless monochrome men. Their bodies and clothes a uniform black, these eerie, life-sized figures crouch in the middle of the gallery. A nearby speaker emits recordings of explosions and protest songs. The wall label and catalogue essay inform us of the traumatic history behind the work—it is meant to recall the 2012 state-sponsored massacre of thirty-four protesters at the Marikana platinum mine in South Africa. It’s another memorial project crying out to remember injustice—but what does it actually do as an artwork? It’s a somber sight, to be sure, and one that will certainly unite viewers in their hatred of such horrifically brutal acts. But the sleek, perfectly executed sculptures are ultimately something defanged, less a provocation than an appealing form. It’s a history lesson, but it hardly amounts to sabotage.

Many of the works on view express this kind of domesticated rage, sometimes in Pettibon-esque drawings and scrawls across the walls (Hardeep Pandhal, Anupam Roy), sometimes in messy, fragmented, large-scale figurative paintings (Chemu Ng’ok). But spending more time in the show, you discover other pieces that give themselves up more slowly, that are satisfied to be artworks, not instigations.

Manolis D. Lemos, dusk and dawn look just the same (riot tourism), 2017. Single channel video, color, sound; 3 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and CAN Christina Androulidaki Gallery.

Reviews of the triennial have lauded Greek artist Manolis D. Lemos’s three-minute video, dusk and dawn look just the same (riot tourism) (2017), and with reason. The fuzzy, low-res video shows a group of sneaker-clad youths sporting long, hooded jackets spray-painted in red, white, and blue, striding through nearly deserted city streets with their backs to the camera. As an electronic soundtrack soars, they accelerate into a run, jostling one another and spreading across the street and onto the sidewalks, some dropping out of view while others lope into an empty square glowing in the early morning sun. It’s a melancholy, aimless gesture, a pretty sort of nihilism. Like most works in the exhibition, it’s accompanied by lengthy didactic material dissecting dense layers of political and social references (the title alludes to Greece’s ultra-right Golden Dawn party; the soundtrack is a remix of a 1936 love song composed during the time of former Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas’s fascist regime; the square is Athens’ historic Omonia Square, named for peace). But these weighty references feel ancillary to the work, which poignantly captures a mood of despair shot through with a quietly insistent hope—a precisely pitched affective register.

Wong Ping, Wong Ping’s Fables 1, 2018. Single-channel animation, sound, color; 13 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery.

Hong Kong–based artist Wong Ping’s thirteen-minute animation, Wong Ping’s Fables 1 (2018), is similarly engrossing. Three absurd tales (a love story between a turtle and an elephant who struggles to choose between monastic and secular life; a plucky chicken with Tourette’s who pursues his dreams to tragic ends; an encounter between a tree trunk, the now-pregnant elephant, and a cockroach on a bus) are illustrated in bright neon colors and a video-game-like visual vernacular, each concluding with a bizarre, aphoristic moral: “Keep laughing even when you are surrounded by corpses,” “To all righteous thinkers, perhaps it is worthwhile to spend more time considering how meaningless and powerless you are.” Often slyly touching on tropes from pop culture and peppered with campy erotic moments, the video initially goes down as something sweetly pleasurable—but ends with an unsettling, slightly sour aftertaste; it’s a sophisticated, knotty work.

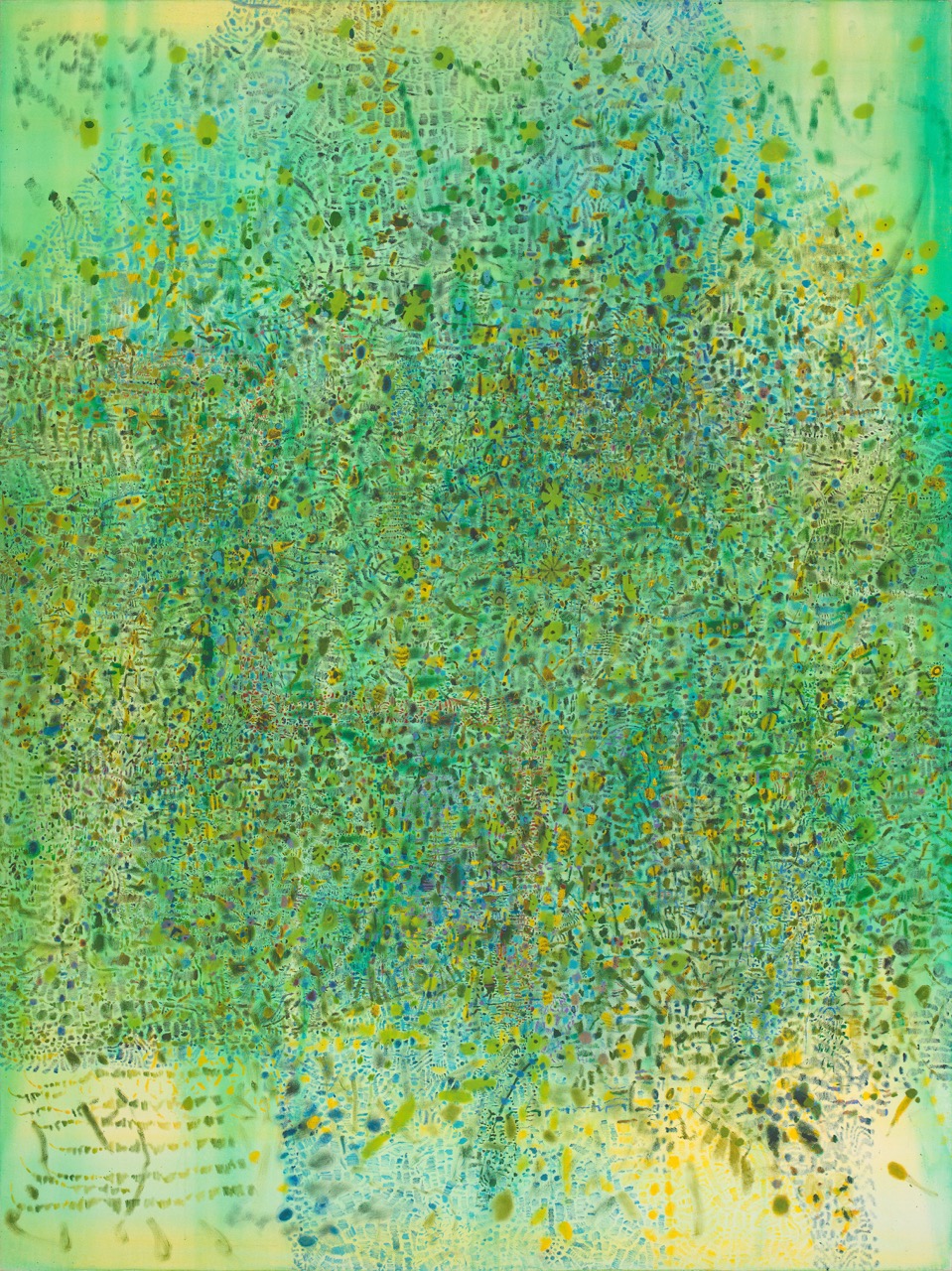

Tomm El-Saieh, Tablet, 2017–18. Acrylic on canvas, 96 × 72 inches. Image courtesy the artist and CENTRAL FINE.

While those videos are some of the strongest pieces in the show, this iteration of the triennial is actually relatively light on new media—that might be a conscious choice on the part of the curators, or could be indicative of a return to painting and physical objects in the post-’80s generation of artists. Of the painters, Haitian Tomm El-Saieh is the standout here. Three large canvases (all 2017–18) offer bright, frenzied abstractions, heavily layered with washes of color and crowded with obsessive markings, requiring close and careful looking. Accompanying texts make much of El-Saieh’s multicultural background (his father is Haitian-Palestinian, his mother Israeli) and his grappling with the cultural legacy of his native Port-au-Prince, but as with dusk and dawn, knowing the backstory is unnecessary. The paintings are mystical and transportive, nervous and trippy—hypnotically unfurling the longer you gaze at them.

Given the current political situation, it’s understandable that the triennial curators would like to raise the stakes, to insist on the relevance and urgency of what we as art workers do, to imagine that our labor could actually pierce the walls of the privileged art world and act upon a broader horizon. But the exhibition truly succeeds when that directive fails—when the artist evades the black-and-white imperative to resist, and instead gives us something subtler, more complicated, and in an enigmatic range of colors.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor of 4Columns. From 2011–15, she was the chief curator of Townhouse, a nonprofit contemporary art space in Cairo, Egypt; she was also a founding editor of Mada Masr, Egypt’s premiere platform for independent, progressive journalism. She is a recipient of a 2016 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.