David L. Ulin

David L. Ulin

A failed father tries to find his failed son in Lindsay Hunter’s new novel.

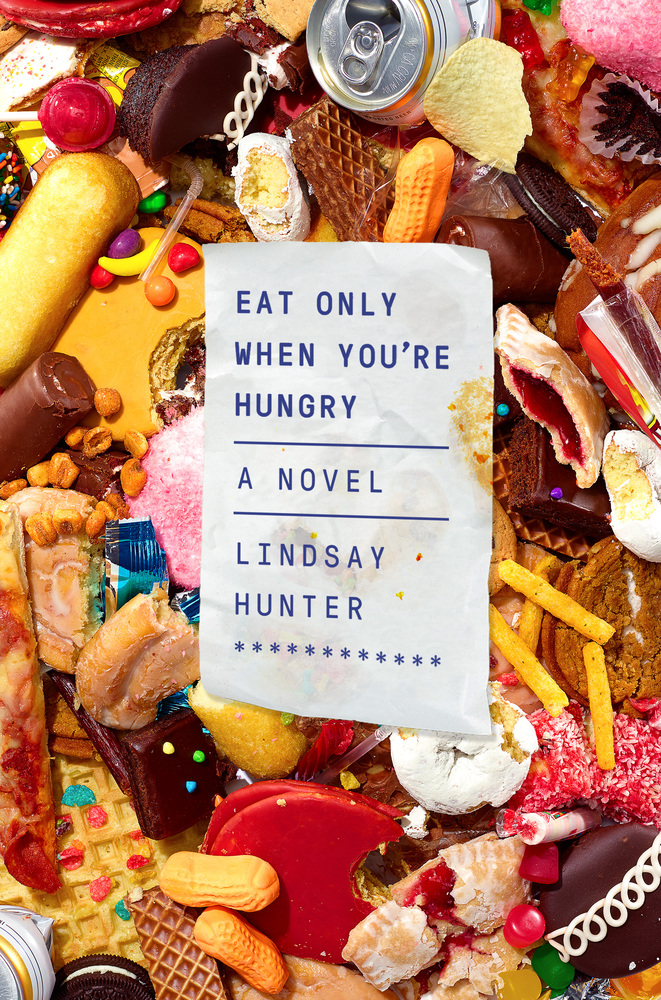

Eat Only When You’re Hungry, by Lindsay Hunter, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 212 pages, $25

• • •

There’s a vibrant ruthlessness at the heart of Lindsay Hunter’s second novel, Eat Only When You’re Hungry, the kind that makes it hard, at times, to catch your breath. In its evocation of a certain type of parenting—white-knuckle, let’s say, involving an out-of-control offspring—the writing brings to mind the work of Harry Crews in its bitter humor and sense of the inevitability of loss. “It’s hard to love someone you don’t like,” Hunter observes late in the book. “It takes everything out of you.” And this: “When he thought of GJ’s childhood he remembered yelling a lot. And when he wasn’t yelling, he didn’t have a lot to say to the boy. What they don’t tell you is it’s all work. Parenting, marriage. They’re both jobs.”

The character doing the recollecting here is Greg: fifty-eight years old, retired, at loose ends, fallen in nearly every way that counts. Bloated from fast food and too much alcohol, he lives in West Virginia with his second wife, Deb, although his heart is with his adult son Greg Junior, or GJ, who has disappeared. GJ is an addict, booze and drugs, with a long history of failed rehabilitations. Still, when he slips out of sight, Greg has the fantasy that he alone can save his missing child. He even looks forward to “stopping somewhere along the way,” Hunter tells us, “having a conversation with a waitress. I’m looking for my son. What came next? Shock? Admiration? He liked anticipating these kinds of things.”

This is a telling moment in Eat Only When You’re Hungry—suggesting, as it does, that the real conflict is between Greg and himself. He wants to be a hero, but he can’t get out of his own way. Just consider the journey to find his son: Greg has no idea where GJ is, no leads on where he ought to look. Since getting together with Deb, he has cocooned himself, keeping a distance from Orlando, Florida, where he once lived with his former wife, Marie, and GJ. Now, however, with his son at risk—or worse—he has no choice but to try to re-engage.

Yet re-engagement, Hunter recognizes, is difficult, especially for someone as lost as Greg. Equipped with a nineteen-foot rental RV—his girth is too substantial for a smaller vehicle—he sets out with the best of intentions, but his attempt to locate GJ takes him in exactly the wrong direction, back to his ex-wife and then his father, the wreckage of his family. It’s a vivid, if not wholly unanticipated, move, since where else would Greg go? He has no other option but to retrace his steps, revisit his own history, because it’s the only thing he knows. Still, what does knowledge even mean for Greg, who seems as incapable of understanding his own behavior—the drinking and the eating, not to mention a predilection for strip clubs—as that of his son? All he really has are memories, which—emerging through a series of deftly rendered flashbacks—illustrate the detachment and the disconnection at his core.

Greg, we realize slowly, has been deceiving himself for years, for decades even, about his intentions and abilities, the quality of his love. As a father, he has been absent at best, and even more, in denial, meeting his son in bars to take the edge off, pretending that everything will ultimately turn out fine. Even his reaction to GJ’s disappearance gets spun through such a filter: “When your son is an addict,” he tells himself, “you can think things like He is missing and that is a welcome distraction and not feel like a monster.” The harsher truth, with which Greg doesn’t want to reckon, is that we are all monsters in aspects of our lives. “He felt a surge of rage course from his trunk into his arms,” Hunter writes, describing the final run-in between Greg and GJ, just before the latter’s disappearance. “Fuck you, he screamed inside his head at his sweaty, sick son. Fuck you for being weak.”

Hunter is addressing the complexity of love, particularly the love between a damaged parent and a damaged child. Indeed, Eat Only When You’re Hungry portrays parenthood as a kind of circular dance, in which there is never any resolution, and more often than not, what lingers is less reconciliation than regret. “He made it a year before his next rehab,” she writes. “He made it another three years. He made it only six months after that. It felt like GJ held Greg by his ankles over a ravine. At any moment he could let go and the whole world would go tumbling past. Soon Greg stopped trying to right himself; he got used to everything being upside down.”

Meanwhile, the futility of the quest is evident to everyone, especially Marie, who becomes one of the book’s unlikely heroes, tough and funny, if not fully accepting of her fate. “Don’t you want the rest of your life?” she asks Greg, lamenting all the time spent on GJ. “If we can’t get those years back, then I want the remaining years I have to be mine.” All the same, when late in the novel the doorbell rings at her condo, both she and Greg fall all over themselves to see if it’s GJ. “He pushed himself onto his knees,” Hunter writes, “but Marie was faster. She tried to run for the door but tripped over the glass and fell, crawling through the shards as fast as she could.”

What are we to do with all this love and longing, imperfect and incomplete though it may be? Eat Only When You’re Hungry eschews easy answers, or resolution in any fundamental way. The novel ends where it begins, with Greg back in West Virginia, his relationships—to Deb, to Marie, to his lost son—as unreconciled as they have ever been. “Today is Tuesday, that much I know,” he tells himself, a refrain that resonates throughout the book. The implication is that we are never sure of anything, not absolutely, and also that perhaps this is enough. Or, as Greg elaborates, about his family: “Impossible to know them with any finality. Impossible to hold them. He felt a sharpness in his eye—the salt of a tear? Or maybe it was just that it hurt to look now. It hurt to see.”

David L. Ulin is the author of Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, which was shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of the Los Angeles Times.