Adam Wilson

Adam Wilson

Do not go gentle into that MFA program: Lucy Ives satirizes a

writer’s workshop.

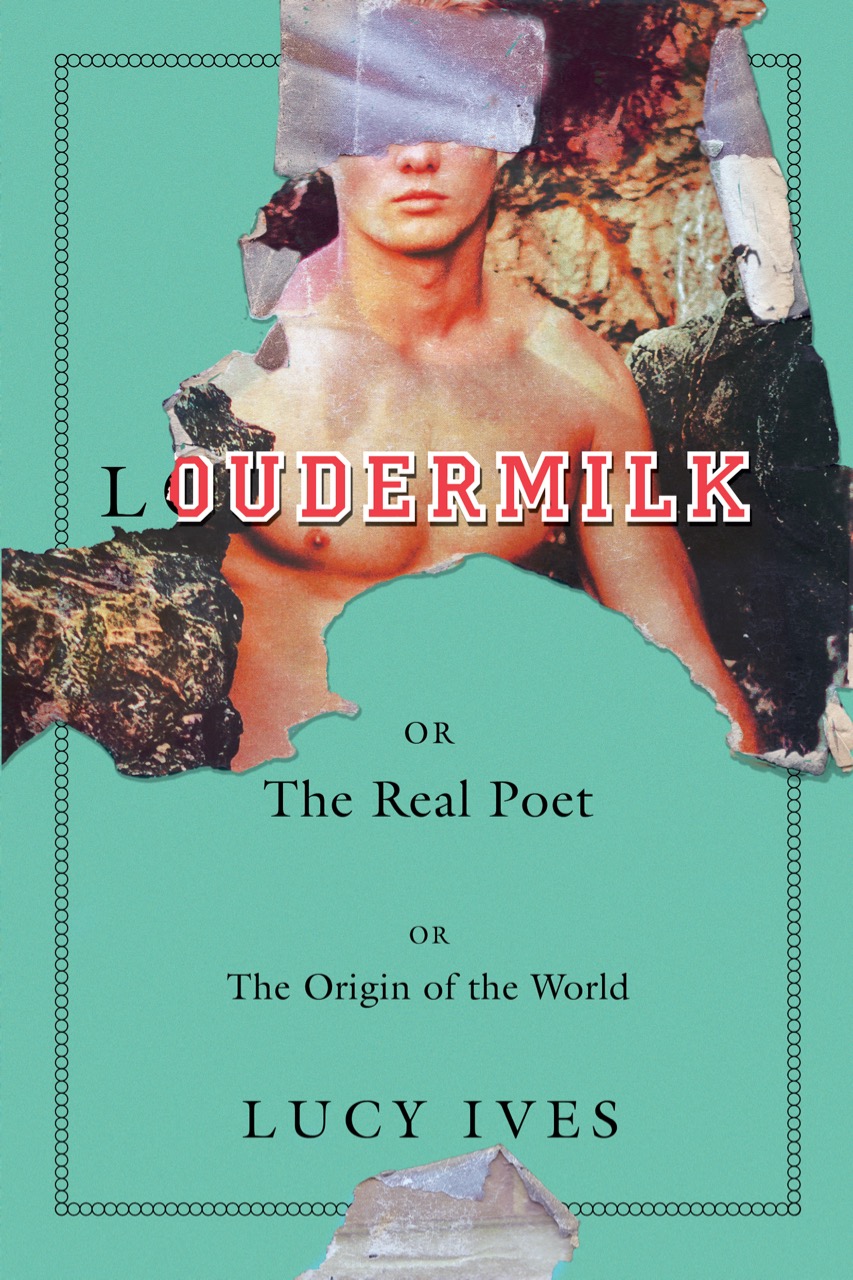

Loudermilk, or, The Real Poet, or, The Origin of the World, by Lucy Ives, Soft Skull Press, 334 pages, $16.95

• • •

In February, the New Yorker’s exposé of literary grifter and low-key psychopath Dan Mallory set the book world—by which I mean a small but vocal corner of Twitter—aflame. Mallory, an editor at William Morrow, and the pseudonymous author of a bestselling and suspiciously derivative thriller, turned out to have fabricated large portions of his personal history, including an Oxford DPhil and a bout with brain cancer. The internet was outraged, at least for a minute. Then the news cycle churned—a TV actor’s staged assault, Trump’s continuing long con—and Mallory faded into the annals of grifters past, alongside other recent standouts: Faux-NYC Party Girl, Blood Test Scammer, Fyre Fest Guy.

I thought of Mallory while reading Loudermilk, or, The Real Poet, or, The Origin of the World, Lucy Ives’s satirical novel in which a fraudulent poet, Troy Loudermilk, infiltrates a fictionalized version of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop (referred to as “The Seminars”) with the help of his ghost writer and reluctant wingman, Harry Rego. The book lifts its conceit from Edmond Rostand’s nineteenth-century play Cyrano de Bergerac—itself a fictionalized account of a real-life con-man poet—and like a play, Loudermilk begins with a dramatis personae, an affectation that tends to indicate one of two directions for a contemporary novel: either it takes itself too seriously, or it’s making fun of books that take themselves too seriously. Thankfully, Loudermilk is the latter.

Its cast includes Anton Beans, “emerging conceptual lyricist” and resident blowhard who “arrived already under contract”; Clare Elwil, nepotistic legacy of a deceased, forgotten poet “whose crowning achievement was, in the early 1990s, to have been profiled in the New Yorker”; faculty couple Don and Marta Hillary, drunk and oversexed, respectively, their marriage in decline; and the Hillarys’ daughter, Lizzie, a stoned teen who likes to urinate in her parents’ office plants. Enter Loudermilk and Harry, mismatched BFFs who met as the only males in an undergrad Feminist Lit class.

Loudermilk, as his name suggests, is voluminously American: blond, beautiful, kinda boring. Harry is the brains of their operation, a bookish introvert “destined to be persecuted by individuals bigger, richer, and stupider than he is.” Loudermilk applied to the Seminars using Harry’s poems, in exchange for which Harry shares Loudermilk’s $25K fellowship and the hypothetical surplus of his female pursuers.

Things proceed as expected: alcohol is consumed, poems are declaimed, dick and fart jokes abound, Loudermilk beds half the coeds on campus. A jealous Beans uncovers Loudermilk’s secret and attempts to unmask him, while the fraudulent Loudermilk’s rise to wunderkind status unmasks the keepers of the literary realm, revealing them as pompous, sex-crazed, superficial phonies.

This brand of campus picaresque resembles Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me (1966), and, to a lesser extent, Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin (1957), both of which were set at fictional colleges inspired by late-fifties Cornell. Ives is a poet as well as a novelist; she’s published a combined nine books in both genres over the previous decade. Like her predecessors, she has a fondness for wordplay, and moves between registers to comic effect. Her poets, for example, are “dreamy masturbators . . . masturbators of a weirdly self-aware and not very physical stripe.” Fariña’s and Nabokov’s novels exposed the American campus’s absurd insulation from world historical events, and Ives has a similar project in mind. Her book takes place in 2003 and 2004, as bombs fall on Baghdad, and George W. Bush campaigns for reelection. The absence of these upheavals hangs loudly over Loudermilk.

Instead, Ives’s episodic novel is set to the campus calendar: summer’s end, a welcome barbecue, a Halloween bacchanal. At the latter, Loudermilk fails to identify the costume of a woman with her head in an oven. He begs Harry to clue him in. “Anne Sexton,” Harry deadpans. Some of this is very funny, but at times Ives’s targets feel like low-hanging fruit. Don Hillary, for example, says things in class like, “I don’t give one donkey fuck what you do while you’re here . . . This is not a contest and I do not give out prizes.” He never amounts to more than a stereotype.

And unlike the Hillarys, the reader doesn’t quite fall beneath Loudermilk’s spell. Perhaps this is the point—Loudermilk is a cipher—but it’s hard to get invested in so vacuous a hero. Harry is a more appealing protagonist, but the novel’s ensemble cast means he doesn’t get enough stage time to fully emerge. There’s nothing analogous in Loudermilk to the pathos of Pnin’s yearning for the lost Russia of his childhood.

A closer cousin of Loudermilk might be the late poet-novelist Gilbert Sorrentino’s 1971 novel Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things, which ruthlessly and hilariously skewered the New York literary world. Like Sorrentino’s, Ives’s novel is meta-textual, sprinkled with the poems and stories that its characters turn in for class. But where Sorrentino’s meta-texts were clearly parodic, what we’re presented with in Loudermilk resists easy interpretation.

At times, for example, Clare’s stories resemble the fiction of Lucy Ives herself—specifically, her novella Nineties—while at others they seem to be poking fun at a certain brand of New Yorker realism. And the text offers no indication of what we’re meant to think of Harry’s poems: Are they garbage or pretty good? When we can’t trust the gatekeepers to tell us what to think, we’re left only with our own unreliable subjectivity.

A successful scam smashes the flimsy authority of the governing body, cracking the illusory presumptions that prop it up. The joke of Loudermilk is that $25K and a meager social kingdom seem like paltry payoffs for such laborious grifting. Why would anyone want to con his way into an MFA program? Loudermilk does it just to see if he can, then finds himself trapped in the existence he’s conjured. Ives’s novel is set in 2003 but it speaks to the current moment. Trump is like Loudermilk—he’s conned himself into a job he doesn’t want.

Adam Wilson is the author of the novel Flatscreen and the collection of short stories What’s Important Is Feeling. His second novel, Sensation Machines, is forthcoming from Soho Press in spring 2020. He is a National Jewish Book Award finalist, and a recipient of the Terry Southern Prize. His work has appeared in the Paris Review, the New York Times Book Review, Tin House, Bookforum, VICE, and the Best American Short Stories, among many other publications. He lives in Brooklyn and teaches regularly at Columbia University’s MFA Writing program.