Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

“My brain is a shelter”: a show looks back at the feminist artist’s

early-’70s paintings.

Mira Schor: California Paintings, 1971–1973, installation view. Image courtesy Lyles & King.

Mira Schor: California Paintings, 1971–1973, Lyles & King, 106 Forsyth Street, New York City, through May 19, 2019

• • •

In Mira Schor’s surreal works from the early 1970s, dozens of which are now on view at Lyles & King, she appears as a kind of spectral action figure, often nude, finding her footing in a perilous and beautiful dream world. The young artist—then in her twenties, a New Yorker attending graduate school at CalArts—rendered the symbols of her psychic landscape in velvety gouache, favoring dusky or night skies, the moon, wild animals, towering palms, and giant succulents with searching spikes. Dynamically composed but curiously still, as if frozen outside of time, these introspective narratives, most of which have not been shown since 1973, if ever, are in possession of an unplaceable intensity. In the small to medium-scale paintings on paper, there are echoes of Henri Rousseau’s enchantingly stilted jungles, the elongated bodies and strange perspectives of Florine Stettheimer’s tableaux, and the witchy desolation of Gertrude Abercrombie’s nocturnal countryside scenes. But I’m hard-pressed to think of a contemporary of Schor’s working along similar lines.

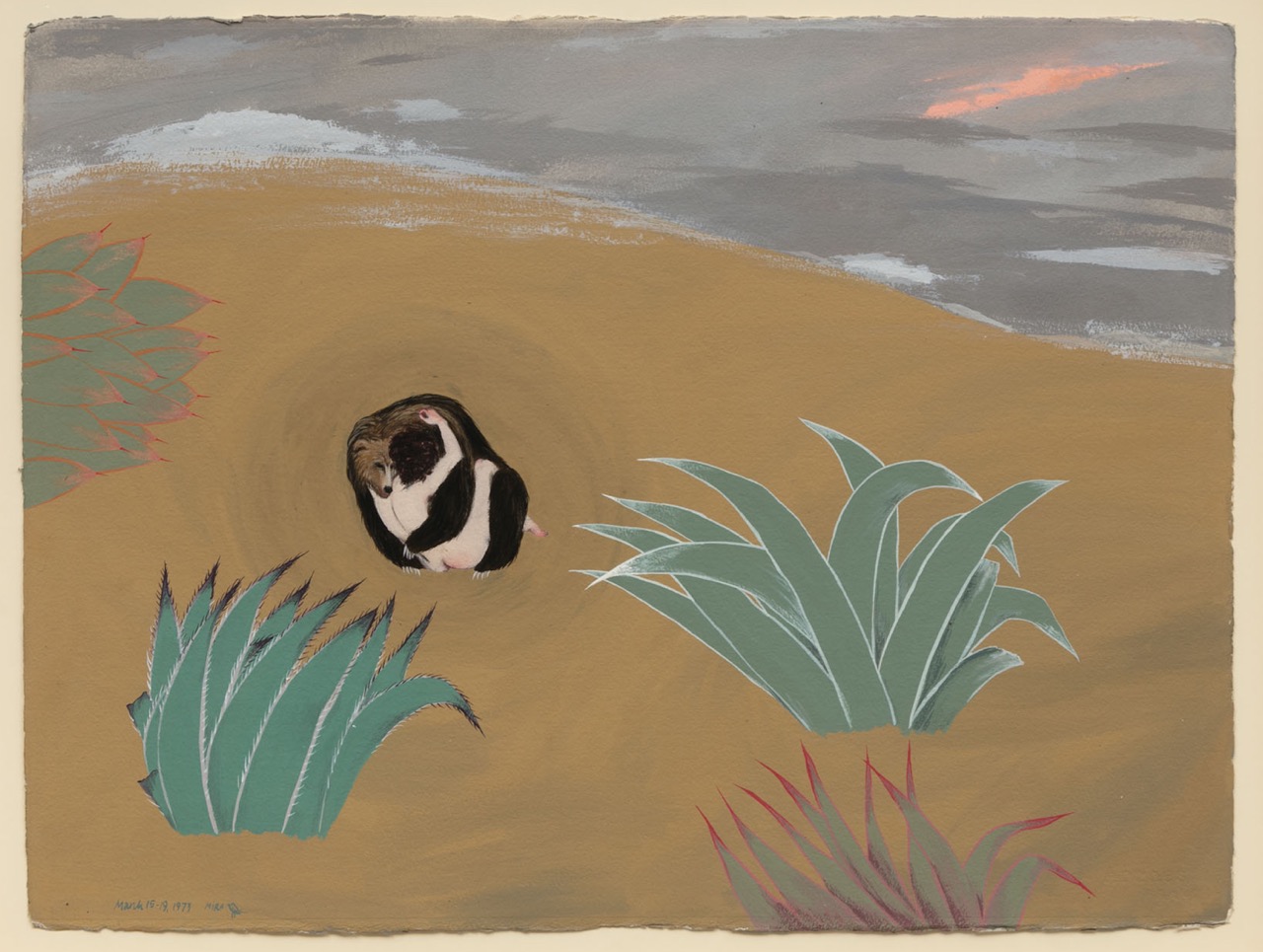

Mira Schor, Bear Triptych (Part I), 1972. Gouache on Arches paper, 22 × 30 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

Her eerie, erotic Bear Triptych (1972–73), a heart-quickening high point in the intriguing exhibition, makes plain the narrative, myth-making quality of her images. Part I depicts the dark-haired Schor seated on a steep sandy slope, her pale form the composition’s bright focal point. Framed by imposing cypress trees and a triangle of sky, she gazes into the eyes of a grizzly bear, its sharp claw resting gently on her shoulder as she wraps a long arm around its neck. In Part II, the sun sets on her weird Eden, and she stands turned away, hiding a bloody hand. It’s unclear what happened—the barbed tentacle of an agave plant is also stained, and the approaching bear is spattered with crimson. Part III delivers a kind of resolution: the artist and animal locked together, having sex.

Mira Schor, Bear Triptych (Part III), 1973. Gouache on Arches paper, 22 × 30 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

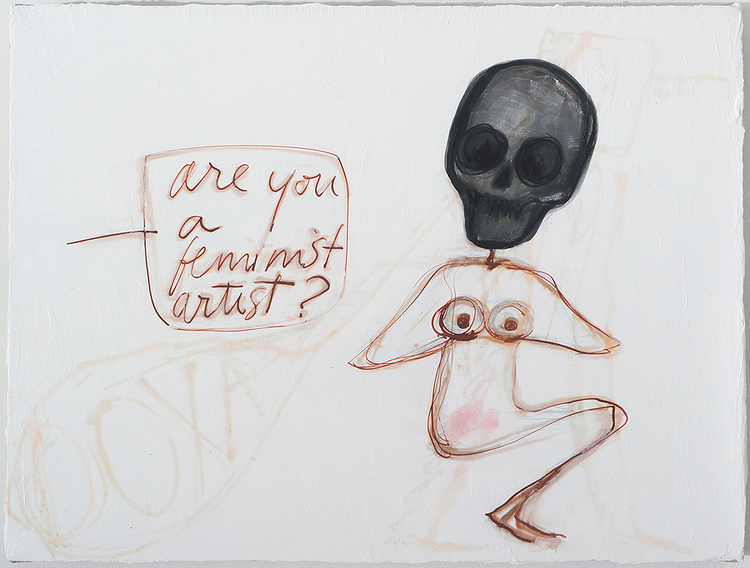

In the decades since, the painter, who is also a renowned author and theorist, has remained loyal to a strain of diaristic interiority descended from that of her fantastic early gouaches, as well as to her critical and sensual preoccupation with the wiles of her history-laden medium. But her fleshed-out pictorial settings have long given way to abstracted or roughed-in backgrounds, or to metaphysical non-spaces that hold ribbons of painted cursive aloft. And while she has continued to depict avatars of the self, unclothed specificity has been traded for naked semiotics; Schor’s “women” are often stick figures with blocks or speech-bubbles for heads. For her last solo show with the gallery, in 2016, she presented swiftly executed iterations of a body reduced to an armature for a skull and breasts, badgered by balloons of text, such as the recurring question “Are you a feminist artist?”

Mira Schor, Are You a Feminist Artist?, 2015. Ink, acrylic on gesso on linen, 12 × 16 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

She always has been. Enrolled in the Feminist Art Program at CalArts in its inaugural year, she was witness and party to a landmark moment in feminist art history; the radical ferment of the program’s separatist experiment, led by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, is the unseen backdrop of Schor’s art from this time. In this light, the paintings here are fascinating in part for what they are not. Her contribution to the fabled Womanhouse (1972)—for which the twenty-one women students in the program, along with their teachers, transformed a deserted Hollywood mansion into a collaborative art environment—is a case in point. Amid the clamor of installations and performances that reclaimed traditionally feminine crafts, or critiqued the home as a site and symbol of drudgery, confinement, and sexist socialization, her in situ Red Moon Room stood out as a painterly wildcard. The immersive self-portrait, whose checkerboard tiles spilled onto the room’s floor, featured her standing in a long dress, big hands gesturing mysteriously in a room that opens onto a barren purple landscape, glowing beneath the title’s red moon.

Mira Schor, Interior with the Moon, 1971. Gouache on paper, 9 ¾ × 14 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

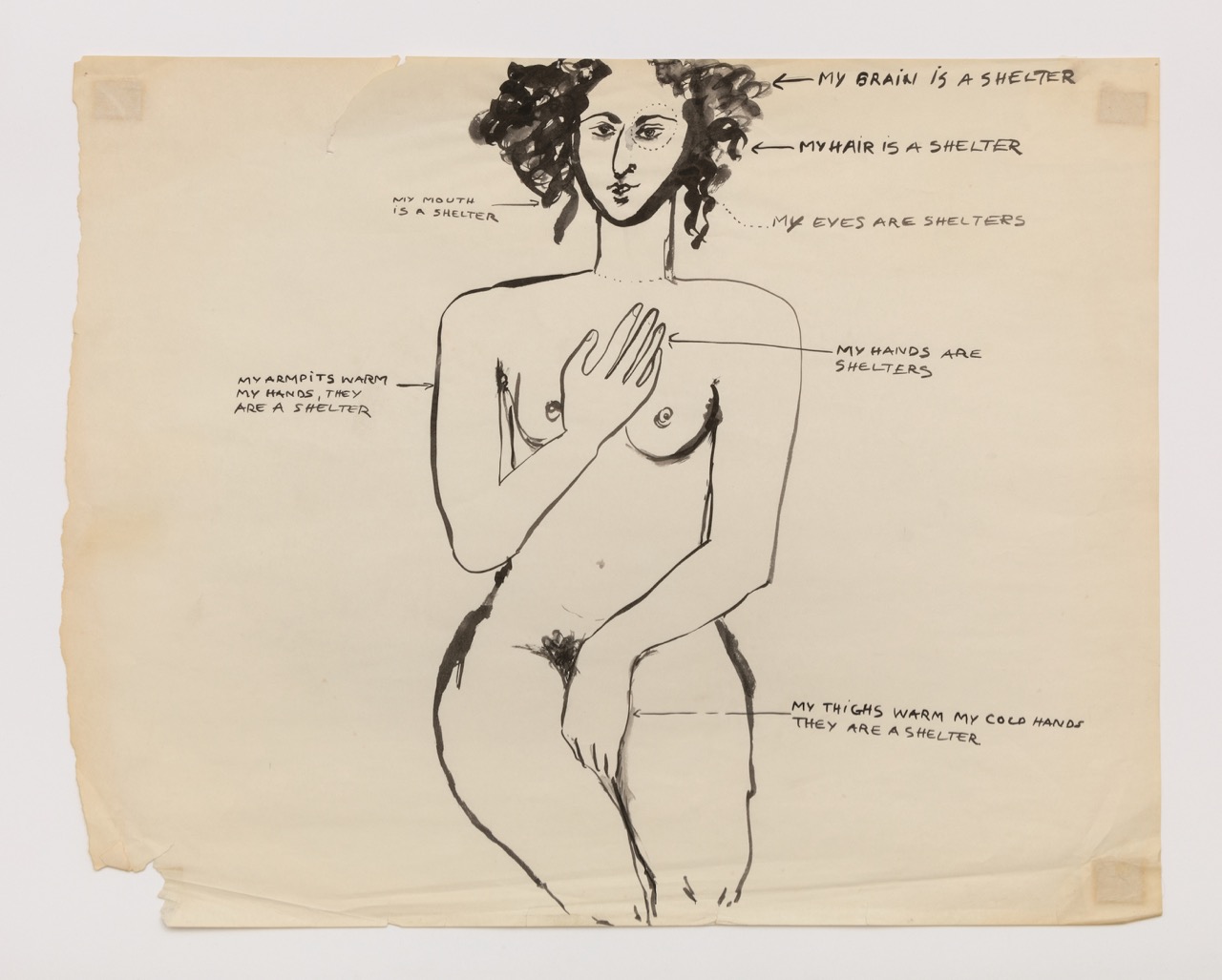

Interior with the Moon (1971), currently on view, which she made the summer before, closely relates to her Womanhouse room, having in common its patterned floor and isolated female protagonist (and two moons); the expressively distorted perspective, luxuriant palette, and inscrutable symbolic precision of both recall the court and garden scenes of Rajput painting, which Schor cites as an influence. But in smaller, compositionally simpler works, such as the ones hung salon-style on a wall in the front gallery—a series of fancifully graphic, Warholesque shoes; a wry one of women in their underwear; a group of gorgeous cacti—she paints with one foot outside her exacting alternate universe. Nearby, the matter-of-factly titled Mira Schor, Feminist Art Program, Class Assignment: Self Image (1972), a drawing on torn, yellowing paper, tells us something about the curriculum’s bent. The quick diagrammatic sketch of her naked form uses arrows to label her body parts. “My brain is a shelter,” she begins at the top, bringing to mind the speech-bubbles, text-images, and metaphors of the body that lay in her future.

Mira Schor, Mira Schor, Feminist Art Program, Class Assignment: Self Image, 1972. 18 ¾ × 24 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

The idealistic program’s innovative pedagogy, which used the consciousness-raising group as a model, recasting art education as a post-patriarchal debriefing process, had its problems, unsurprisingly. What could go wrong at this boot camp of forced self-actualization, conducted by two feminist artists who were themselves undergoing a period of artistic upheaval? Both women were rejecting the values of the male-dominated art world, in which they, against the odds, had won some success. Schapiro, who had survived the New York AbEx boys’ club in the 1950s to become a hard-edge painter in the 1960s, was now making large-scale fabric collages (“femmages,” she called them). Chicago, who had mastered the skills of auto-body painting to made slick abstractions in line with the pop-minimalist Finish-Fetish movement, was embracing performance, china painting, and, most famously, the vulvar forms that would become the basis of her monumental installation The Dinner Party (1974–79).

Schor clashed with both of these formidable personalities not only over their teaching styles, but also their ideas. “Judy has her naive obsession about ‘central core imagery’—which some of the women swallow,” she complained in a letter to her friend, the painter Yvonne Jacquette, two months after the closing of Womanhouse. Referring to Chicago’s theorization of a tendency in women’s art to use round or radial shapes (as well as explicit vaginal references) to represent embodied female experience, the alienated Schor illuminated one of feminist art’s early fault lines, landing on the side that rejected essentialist iconography.

Mira Schor: California Paintings, 1971–1973, installation view. Image courtesy Lyles & King.

There’s a scene in Johanna Demetrakas’s documentary Womanhouse (1974) in which the students, sitting on the floor of the old mansion’s living room, commiserate about their artistic self-doubt. Chicago chimes in, recounting a recent frustration, where she went back and forth for an hour, deciding on the dimensions for a drawing. “I couldn’t get inside and connected to what I wanted,” she proclaims. “Every time, every decision,” she tells the younger women, “it’s that kind of process.” They must shut out the noise of the external world, she demands, to ask, “What do I want?” Demetrakas includes the briefest reaction shot of Schor, who nods almost imperceptibly at her teacher’s passionate words. Perhaps to the young feminist artist, who would soon leave the program, Chicago’s instruction didn’t mean so much. Schor’s California Paintings show she was already working with precocious certainty.

Johanna Fateman is a writer and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She is coeditor of Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, published by Semiotext(e). She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a book.