Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Beauty, ugliness, an equalizing gaze: the artist channels the work of poet Wanda Coleman to share her vision of Los Angeles.

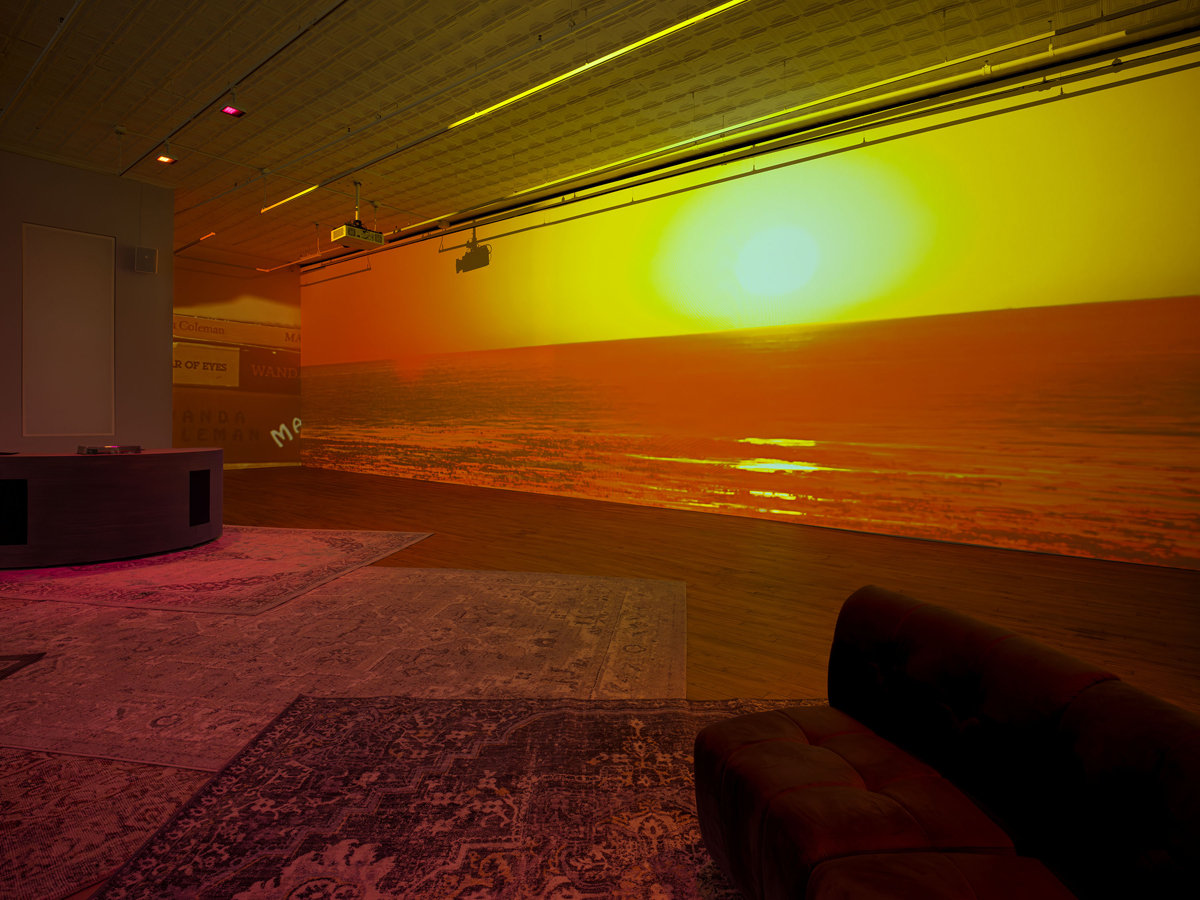

Cauleen Smith: The Wanda Coleman Songbook, installation view. Courtesy 52 Walker.

Cauleen Smith: The Wanda Coleman Songbook, curated by Ebony L. Haynes, 52 Walker, 52 Walker Street, New York City,

through March 16, 2024

• • •

With The Wanda Coleman Songbook, the installation at the center of Cauleen Smith’s latest New York solo show, the artist has transformed 52 Walker into the ideal space for deep listening and slow looking. The floor is covered with worn carpets, the lighting is dim, warm, and inviting, and the couches are remarkably comfortable. It’s a place where you feel like shedding your coat, plopping down your bags, and settling in. Drop the needle on a thirty-two-minute vinyl on the minimalist DJ table, watch the videos projected all around you, take in the scent wafting through the gallery (a mix of grass, eucalyptus, gasoline, ocean salt, flowers, and citrus, from what I could sniff), and find yourself immersed in Smith’s vision of Los Angeles.

Cauleen Smith: The Wanda Coleman Songbook, installation view. Courtesy 52 Walker.

That portrait is a complicated one, rooted in a clear-eyed, contradictory, ambivalent love—neither wavering nor idealizing. Smith lived in LA in the 1990s, making experimental films as well as a feature, Drylongso, which has found a second life with a 2023 Criterion Collection edition and a theatrical release. When she moved back to the city in 2017 after stints in Texas and Chicago, she writes in the liner notes for the EP featured in the exhibition, “I found myself looking for way-finders to help me navigate a terrain which was simultaneously familiar and alien.” One of those way-finders was the poetry of Wanda Coleman (1946–2013), known as the “unofficial poet laureate of Los Angeles.”

Cauleen Smith, The Wanda Coleman Songbook, 2024 (still). Courtesy the artist and 52 Walker. © Cauleen Smith.

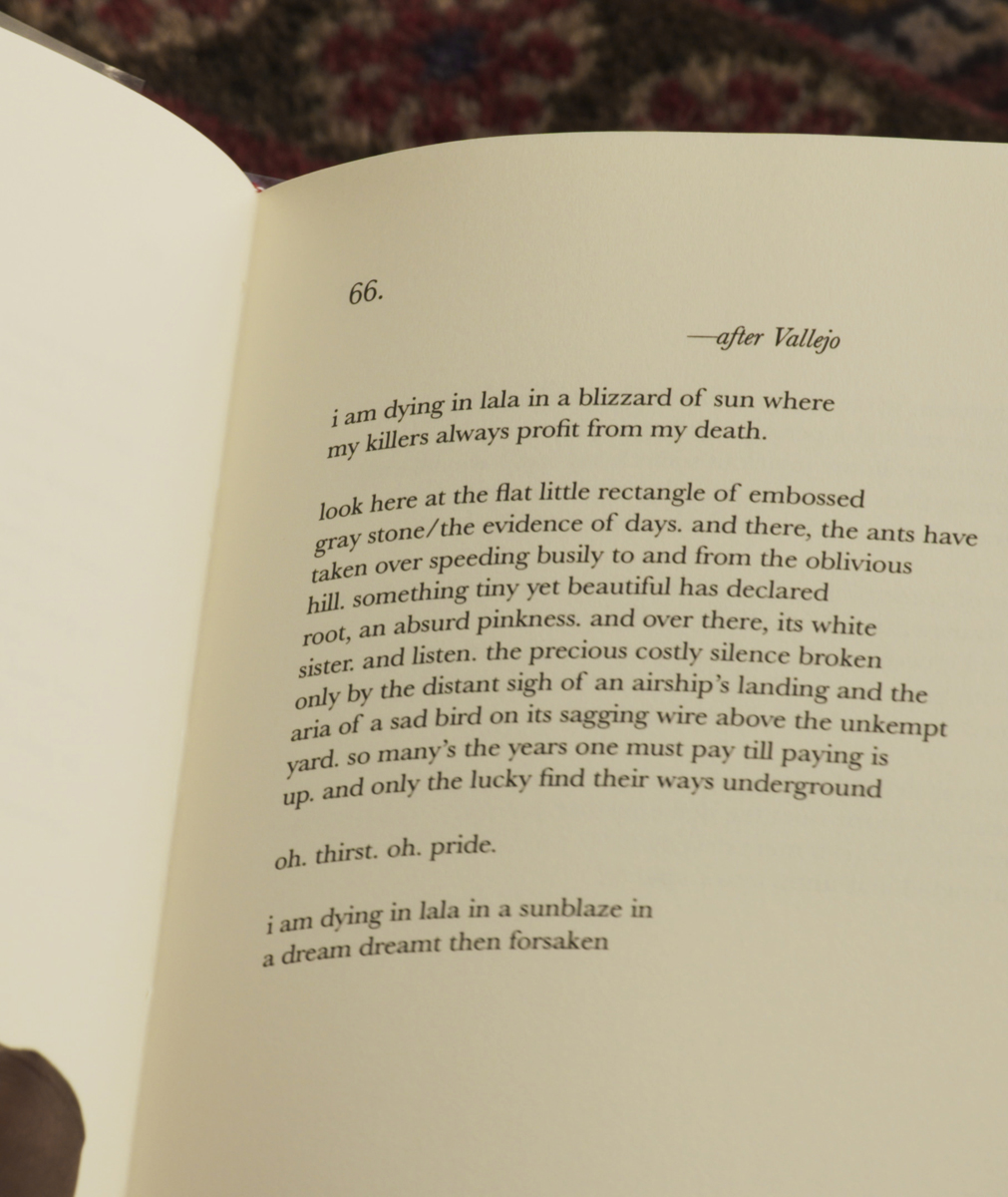

Coleman’s word craft is beautiful and brutal at once; her work offers up a layered, interpenetrating description of Black womanhood and of a city that has been both its home and tormentor. In her poetry, vulnerability and aggression are inextricable. She was a deeply unsentimental writer, and fiercely refused any whiff of respectability politics. (Her 2002 Los Angeles Times essay on Maya Angelou’s A Song Flung Up to Heaven is a diss track in the form of a review so unrelenting that it got Coleman banned from a reading at one of LA’s most important African American bookstores.) Coleman’s verse is remarkably musical—“from the infinite alphabet of afroblues . . . i cull apocalyptic visions,” she wrote in “American Sonnet 61” (1998). That quality inspired Smith to invite artists to interpret a series of Coleman’s poems, including the aforementioned sonnet. There are tracks by singer and cellist Kelsey Lu; multidisciplinary performer, vocalist, and writer Shala Miller; poet, musician, and activist moor mother with trumpeter, composer, and DJ Aquiles Navarro; singer Meshell Ndegeocello, who won a Grammy this year for best jazz album; guitarist and composer Jeff Parker and his daughter, singer Ruby Parker; singers and songwriters Alice Smith and Jamila Woods; and the avant-garde music collective Standing on the Corner. Some turn Coleman’s lines into spoken-word performances accompanied by moody music in a range of genres; others sing her poems; still others home in on resonant phrases or single stanzas, transforming them into haunting refrains.

Cauleen Smith: The Wanda Coleman Songbook, installation view. Courtesy 52 Walker.

“In that Other Fantasy Where We Live Forever” (2001), reimagined on the album by both Alice Smith and by Jeff Parker and Ruth Parker, presents the city as the prism through which Coleman remembers, with tender nostalgia and deep heartbreak, a past love. When she recounts the relationship’s end (“when you split you took all the wisdom / and left me the worry”), she seems to be speaking as much about the loss of Black Los Angeles as she is about the breakup. (From its high point in the 1970s and 1980s, the African American population has dropped consistently, thanks in large part to gentrification and other forms of structural racism.) Cauleen Smith’s cinematic choices reiterate and translate Coleman’s admixture of longing and grief. Observations from a day in the life of the city, from sunrise to sunset, appear on two long walls—suitable for panoramic shots—and two narrow segments of a third. There is the sea, of course, and beaches, but also Pacific Park amusement park, flower stalls, a neon motel sign, cars on freeways, crows on power lines, purple bougainvillea, the Hollywood Hills, oil wells, hikers in twilight, a skateboarder, liquor stores, and more. Tony Tasset’s “Rainbow,” a ninety-four-foot-high painted steel sculpture installed at Sony Pictures Studios (formerly the MGM lot) shows up, as does Watts Towers, the sculptural fantasy built between 1921 and 1954 by self-taught artist Simon Rodia out of broken pottery, old pop bottles, seashells, and other humble materials. A Chinatown faux-pagoda and Yves Klein–blue coral reef–like structure embedded with Asian souvenir-shop figurines is carefully examined by the camera, becoming a kind of landscape. An image of graffiti reads “DEATH TO TAGGERS” next to skulls-and-crossbones. A parade of lowriders drives past. Every so often, we see a stack of Coleman’s books on a table or arranged on a shelf, or a close shot of a single page, or a hand riffling through a volume faster than we can read it. The music from the album plays alongside this footage without being a synced soundtrack—it depends on viewers to operate the turntable, so there is an everchanging interplay between audio and video.

Cauleen Smith: The Wanda Coleman Songbook, installation view. Courtesy 52 Walker.

Cucolorises, contraptions used in the film industry to cast shadows or silhouettes, create non-cinematic imagery in corners and behind the DJ table. One throws a helicopter on the wall; another, based on a viral photograph by Estevan Oriol (“the Ansel Adams of LA”), presents “LA fingers”—a pair of ring-clad hands forming initials of the city. Yet another shows an Olmec head with a broad nose and lush lips—a nod to Afrocentric myths that have arisen around the possible origin of these colossal sculptures (and the Olmecs themselves) in Africa.

Cauleen Smith, The Wanda Coleman Songbook, 2024 (still). Courtesy the artist and 52 Walker. © Cauleen Smith.

Smith’s visuals are precise: though not an exclusively working-class view of LA, or a Black and brown one, it is at least one that sees the city’s toniest neighborhoods from a distance, and its less-privileged areas proximally. There is a leveling effect in her shooting technique—the camera moves slowly and deliberately, no matter what it fixes upon, and there is a softness to the editing. There is no judgment here, no moral hierarchy—no indication that what we are looking at from one moment to the next is good or bad. Beauty, decrepitude, and sheer ugliness exist in equal measure. Smith’s camera tracks horizontally and vertically, but—as far as I could tell—never zooms in; people or things may move toward it or away, but it never impinges on their space. For decades, the classic, almost clichéd views of Los Angeles have been shot from police helicopters, whether OJ Simpson’s slow-motion ride in his white SUV or Rodney King’s beating, or any number of less notable car chases and pileups. Smith avoids this point of view. She doesn’t look down on the city—figuratively or visually—but only across and up. When we do see a clip of a police helicopter, it is from the ground, spied behind one of Watts Towers’ spires.

Cauleen Smith, The Wanda Coleman Songbook, 2024 (still). Courtesy the artist and 52 Walker. © Cauleen Smith.

These formal strategies are also political strategies—a refusal to heroize or demonize; an insistence on witnessing everything, including those sights too often overlooked; a call to sit with the contradictions of Los Angeles, and perhaps of the whole complicated, infuriatingly vital world we live in. “LA is a shy one, a real one, and a terrible beauty,” Smith writes in the liner notes. “You can’t really see how gorgeous it is in a drive-by, you have to sit with the banality, the horrors, the wildness of the city until it begins to become legible.” With The Wanda Coleman Songbook, she’s created the perfect space for us to do just that.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns. Her new book, on the treachery of emotions, will be published by Floating Opera Press this spring.