Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Walls Have Ears, the band’s trailblazing 1985 album, gets

its first official release.

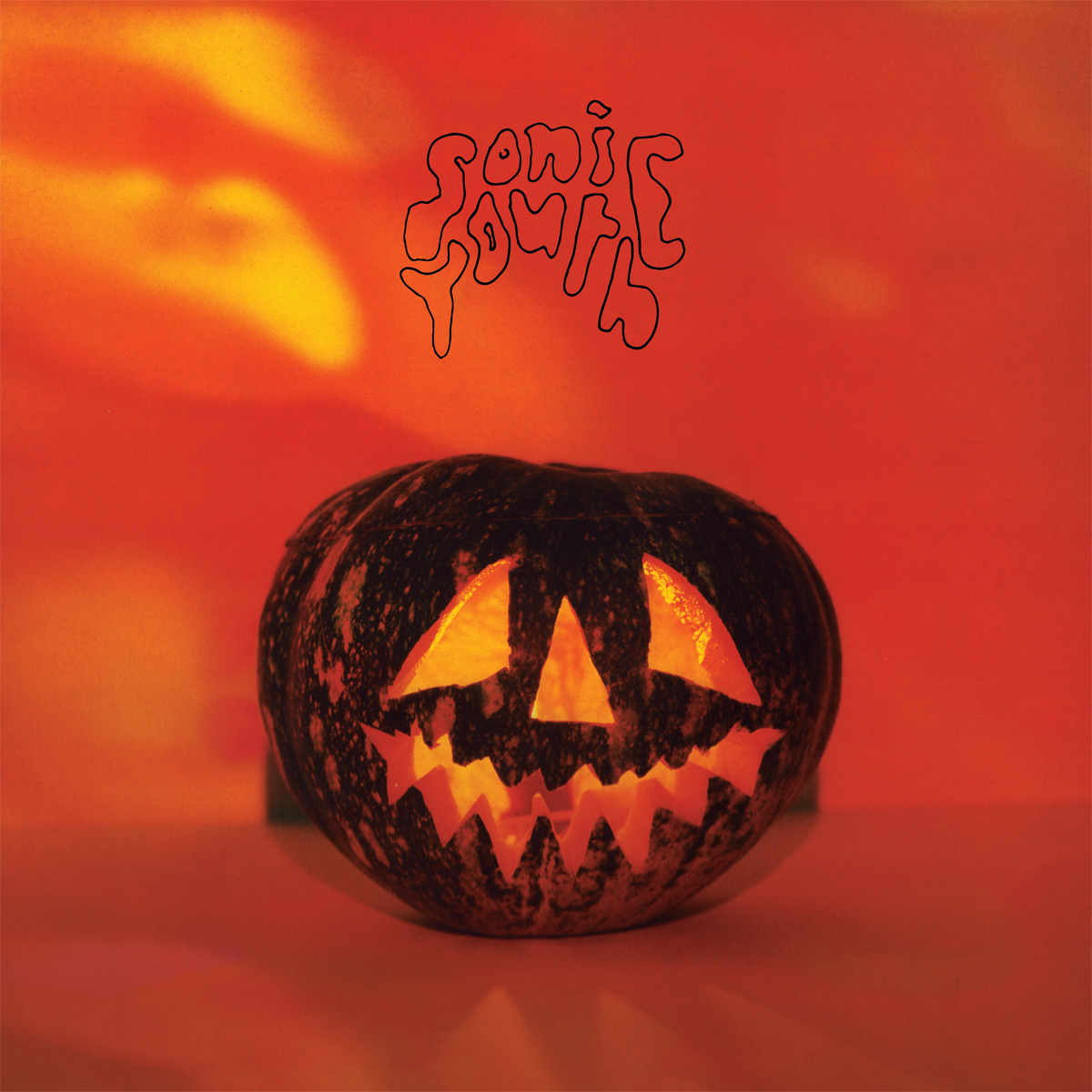

Walls Have Ears, by Sonic Youth, Goofin’ Records

• • •

Some memories are just weak—sour nostalgias and timid regrets that today is just today. Some, though, are firecrackers that can be lit anew every day, blooming to remind us that history holds the sign of miracles. Sonic Youth’s 1985 live album Walls Have Ears is the latter. What Sonic Youth did onstage in 1985 was the soft earth that grew much of what happened in rock for the next fifteen years, including but not limited to My Bloody Valentine and Nirvana. The band was coming out of a New York scene that had loosely been termed No Wave, which was a sort of dismantling of rock that decided to keep the guitars, meaning it was a dialectic rather than a break. Glenn Branca’s ensembles used masses of electric guitars tuned in nontraditional ways. Mars was a guitar band that reduced rock to a monomaniacal roar, and Lydia Lunch distilled all the lead singer macho into a different kind of yell, the sound of a woman piledriving bravado back into itself. All of these bands were decidedly unfriendly and that was the point—the No in No Wave was not optional.

Sonic Youth came out of this—both Lee Ranaldo and Thurston Moore did time with Branca before starting the band along with Kim Gordon—and by their third album, Bad Moon Rising, they had started to find ways to capture all of that No Wave energy and somehow combine it with the rock they were also disavowing. (“Bad Moon Rising” is, after all, the name of a Creedence Clearwater Revival song, so the disavowal was always in flux.) When Lunch herself passed an early tape of Bad Moon Rising to British promoter Paul Smith, he loved it so much he started a label to put it out in England: Blast First. Sonic Youth went to England for shows in early 1985 with drummer Bob Bert, and by the time they returned to England in the fall, they were working with Steve Shelley, who remained their drummer for the next twenty-six years. Smith became what Ranaldo called the band’s “unofficial manager,” and, as “a gesture of goodwill to try and raise some cash for our living expenses,” he put together Walls Have Ears from three shows in the UK, one with Bert and two with Shelley. The problem is, he didn’t tell the band he was doing it. “We were totally bummed out that he had done this without asking us or without our approval,” Ranaldo told me. This was “a hiccup in an otherwise fruitful partnership,” and the band kept working with Smith until 1990. They also, quite concretely, believe in this album.

The band has now reissued Walls Have Ears for its first legitimate release, adding a few songs but keeping the gorgeous jack o’lantern cover. At the time, Walls Have Ears was an actual holy grail. It was the first memory I have of seeing a “bootleg” recording of an active, current band. The printing seemed luxurious, and my older friends who had $40 to spare said this was the real deal (which is the kind of thing people who spend too much on records always say). The best I could do was a tape of the album from one of those friends, and it was more than enough.

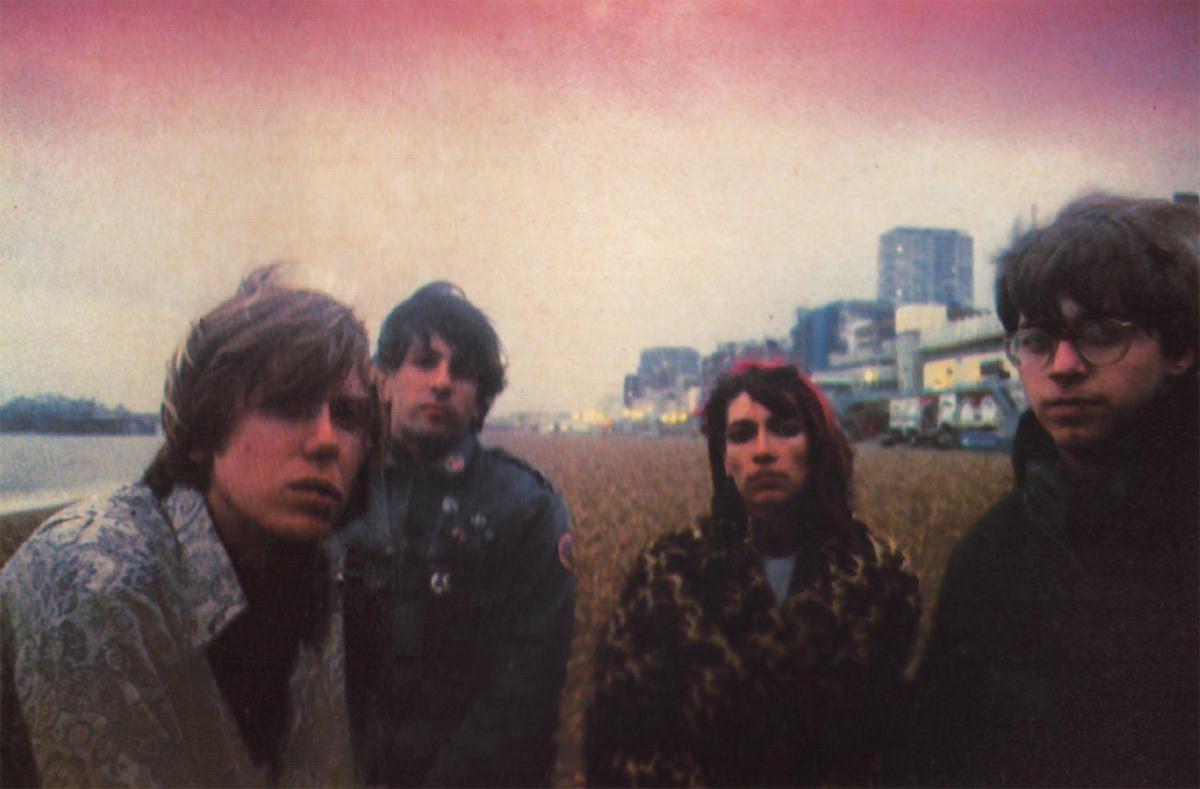

Sonic Youth. Courtesy Riot Act Media. Photo: A. J. Barratt.

This was the sound of a world coming into view, a band completely united and twice as musical as acts that allegedly played “better” than these kids tuning their guitars this way and that. “We were furious and playing furious shows and we were loud, anarchic and kind of all over the place,” Ranaldo told me, “kind of half a comedy act and half dead serious.”

“Brother James” appears here twice, a big slab of downstrokes and subtle harmonic resonances hammered out as unsubtly as possible. Early in the song, all of the guitars hang together and bend down and up almost a whole step. It’s the first draft of the whammy bar rollercoaster dip that Kevin Shields made central to My Bloody Valentine—that weightless, unbodied embodiment where all the noise and fury switches immediately into this sharp lightness. Kim Gordon growls the words like a resistance fighter face-to-face with her comrade: “Take my hand you might as well, we’re going straight to hell.” It seems like Brother James is driving to meet God with her, but who knows. The version with Bert (retitled “Brother Jam-Z”) is a brutal summoning, and the version with Shelley has less of the drums in the mix but more of a pulse, so you get the scrabbly squirrel lunge of the strings with this new kind of anxious ecstasy beneath it.

The comedy was there in Thurston’s stage banter, like “we’re gonna do a couple of Alice Cooper songs.” (They did not.) The songs were joined together with cassette tapes playing snatches of Stooges and Madonna, whom Ranaldo confirms the band “loved.” “People thought we were just making fun of all that stuff, but we weren’t,” he said. “We were totally enthused that there was aboveground music that we could relate to.” The stage tapes made it more like what Ranaldo called “a modernist turn, where you were listening to an hour-long set that had all these different episodic things going on.”

Shelley, drummer for a Michigan band called the Crucifucks, had ended up staying in Kim and Thurston’s apartment while they were doing dates in the UK with Bert, who quit at the conclusion of the tour. “So we came back to New York and there was Steve sitting in their apartment,” Ranaldo said, “and without thinking or without auditions or anything, we just said, ‘You want to be our new drummer?’ basically. And that was the beginning of Steve joining the band.”

One of the first things Shelley wrote with Sonic Youth is “Expressway To Your Skull,” a high point on EVOL, an album that had yet to come out when Walls Have Ears appeared. The song begins with a big open tuning, strummed as if life is a breeze. The band kicks in with a repeating two-hit motif woven into what is more or less a single chord drone. Thurston sings about killing “the California girls,” which is demoted to an “exploding load” and then drifts into talk of a “mystery train” and a “three-way plane,” meaning the sex and murder are confused and the song becomes a small rockslide on Thurston yelling “to your SKULL.” This live recording makes the later studio version irrelevant, in its power and also in its quiet, because the most important part of this tape, for young Sashi, was the final five minutes of this song. Thurston and Lee and Kim tap the backs of their guitar necks to create a ribbon of sustain while Steve taps his cymbals. The way out of rock music here was not to make it scarier, but to let it simply dissolve, to let genre die. Every time I hear this, I find myself at the same big lake, an expanse where there are no arguments about rock, just a long, wide view of reflected light.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was recently published by Semiotext(e).