Hanif Abdurraqib

Hanif Abdurraqib

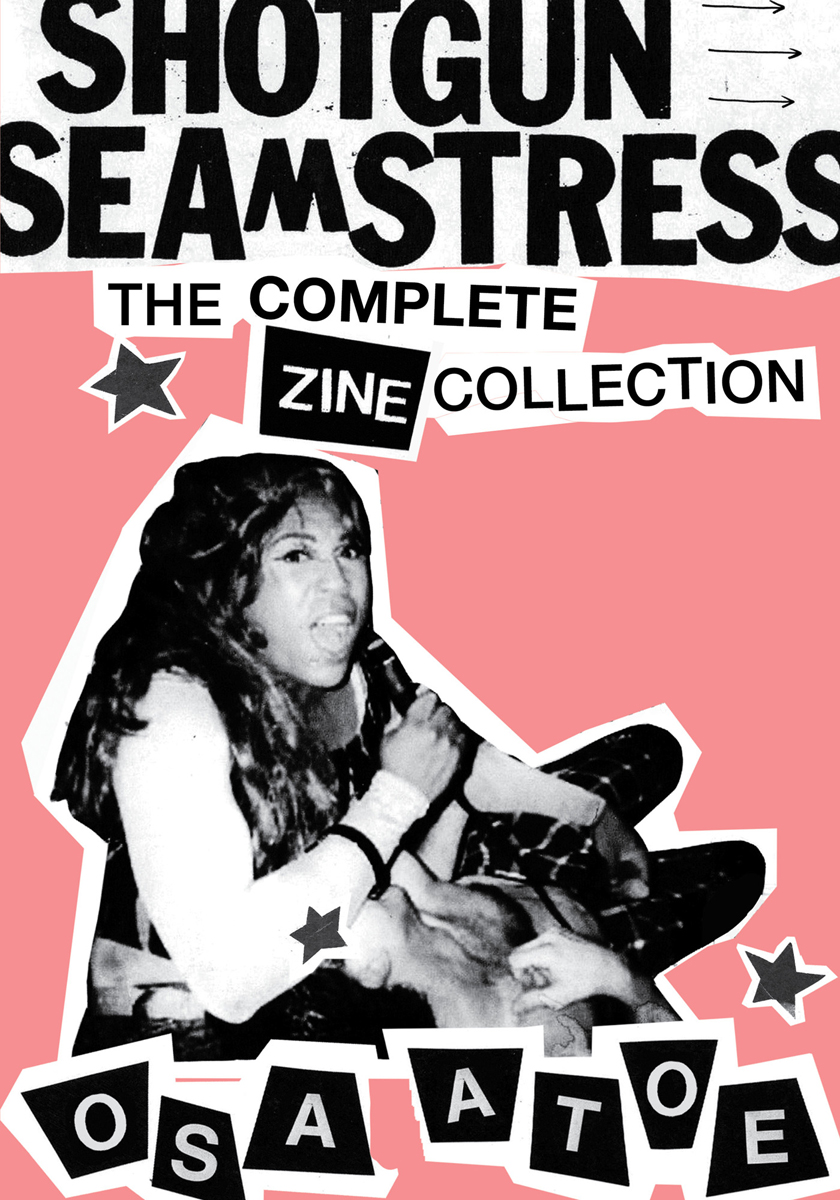

The legendary zine celebrating the mid-2000s Black punk scene, collected for the first time in a complete anthology.

Shotgun Seamstress: The Complete Zine Collection, by Osa Atoe,

Soft Skull Press, 368 pages, $40

• • •

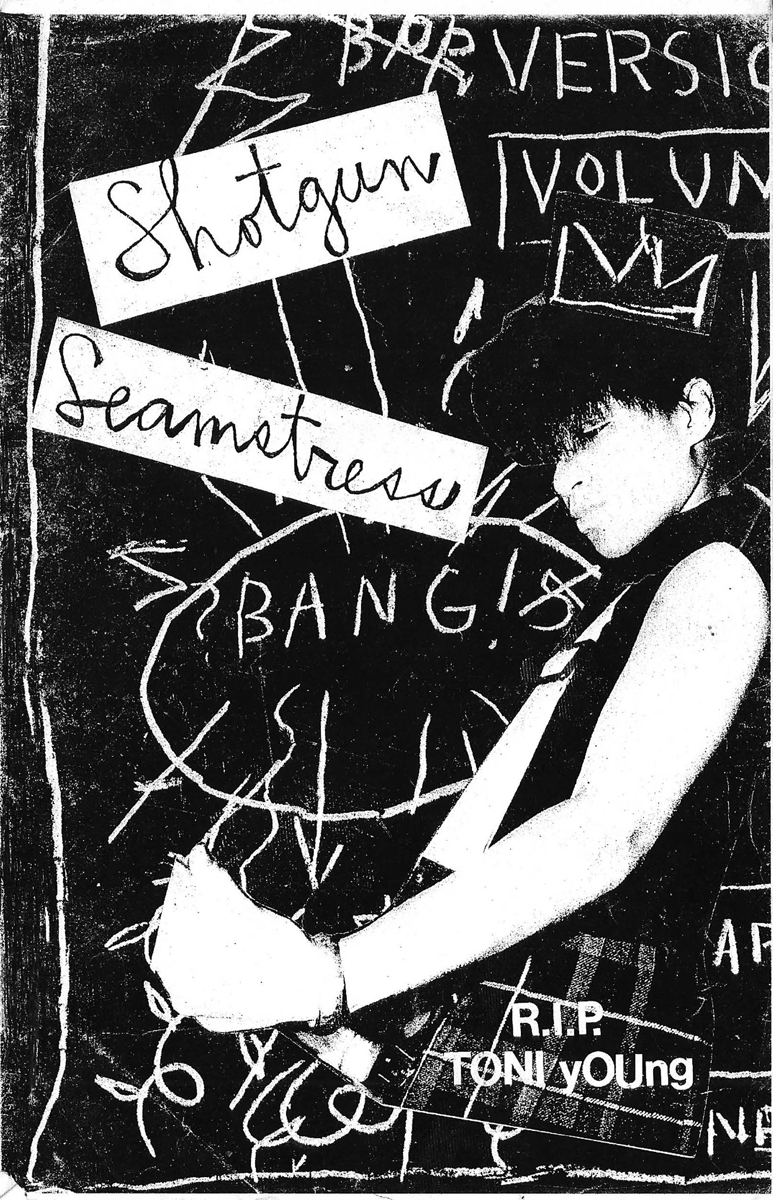

I’m not sure of the year, but I was introduced to Toni Young—a DC hard-core legend who died unexpectedly in the ’80s—through the zine Shotgun Seamstress. In the days when I would most aggressively traverse the Midwest punk scene(s), in the early to mid-2000s, going from my hometown of Columbus to Dayton, to Chicago, to Pittsburgh, to Detroit, and so on, there were always punks with a stash of assorted zines from sometimes far-off places. And that’s how I first saw Toni Young. In the infantile moments of the internet, before it became The Internet We Now Know, I would search for photos of Young, or ask about her on the music message boards I frequented, with little success. All of the earliest visuals I saw existed in zines, black-and-white shots pasted on white pages. In one picture, she was wearing a checkered skirt and a black polo, running her fingers along the bass strings. Droopy socks and a pair of Chuck Taylors that had taken a beating not even the monochrome of the image could obscure. She looked like the punks I knew, the ones I would sporadically see at shows. I was lucky, in certain ways. Sure, I was the only black punk in the room once in a while. But more often than not, especially in Detroit, especially in Dayton, there was a group of us, cutting knowing glances in each other’s direction, meeting up outside to commiserate after the music died down and before we all retreated back to our separate pockets of the Midwest, sometimes sharing phone numbers or online usernames.

From Shotgun Seamstress, by Osa Atoe. Courtesy the artist / Soft Skull Press.

The gift of Shotgun Seamstress, both then and now—as all of the issues created by the artist Osa Atoe beginning in 2006, out of Portland, have just been anthologized and released in a single volume by Soft Skull Press—is one of history. Even if you weren’t the lone black punk wallowing in the back of a packed venue, even if you had a crew to make space for you in the pit, to joke with you on a walk back to the car, to throw hands when the time called for it, there was a point, for me, where it felt like the present mode of the black punk had simply arrived, unattached from lineage. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe that black punks existed before me and mine, it’s simply that I didn’t have the knowledge or text or imagery to work backward. To see Toni Young was to be shown a past precedent that made my present possible. It illuminated a shared lineage that I felt connected to—all of us black and fighting for our own space in our own corners of the punk ecosystem.

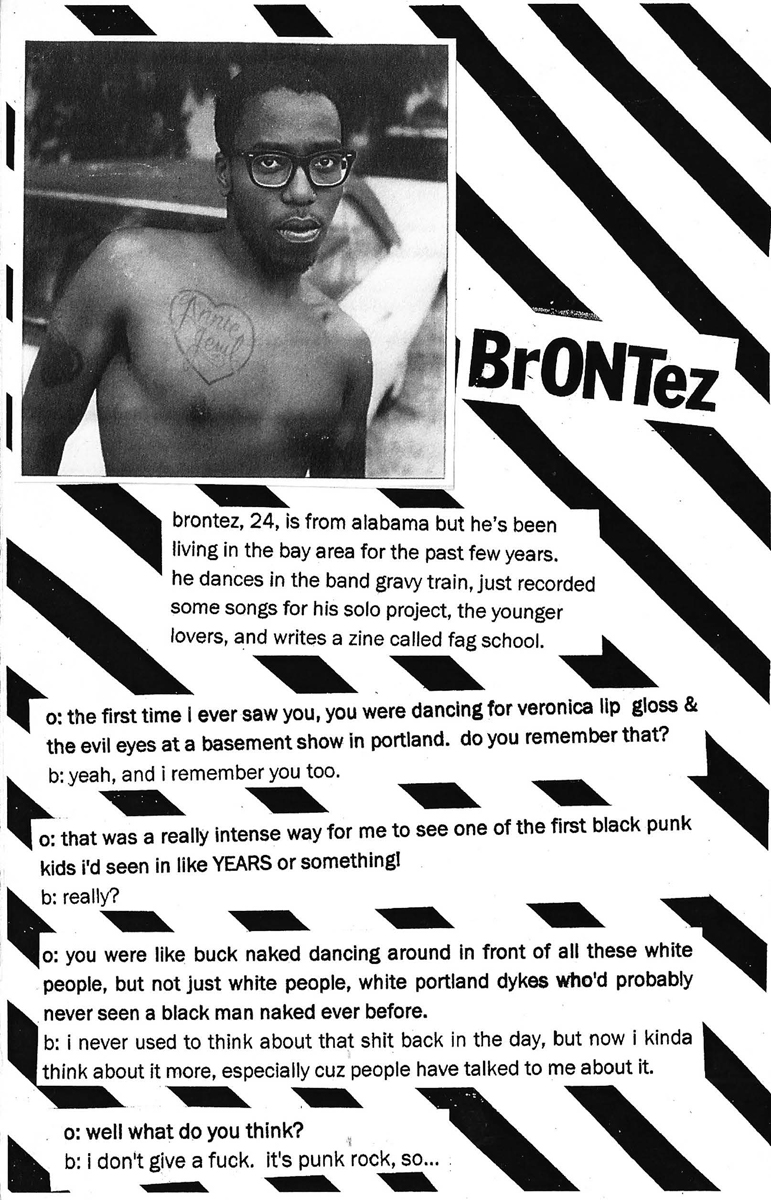

To look at Shotgun Seamstress in 2022, collected in this way, is to be met with the best sense of overwhelm. Even if (or maybe especially if) one had never encountered the zine before. The book does the reader the benefit of presenting the zines in their original form, with their original artwork, the familiar uneven margins that are the result of even the most careful DIY zine-making. This makes it a sort of aesthetic time machine (and, occasionally, a very literal one). Take, for example, an interview with a then-twenty-four-year-old Brontez Purnell, in the era of performing with the band Gravy Train in the mid-2000s, a flashback that will be especially surprising for those who only came to Brontez recently, through the brilliant writing of his current era.

From Shotgun Seamstress, by Osa Atoe. Courtesy the artist / Soft Skull Press.

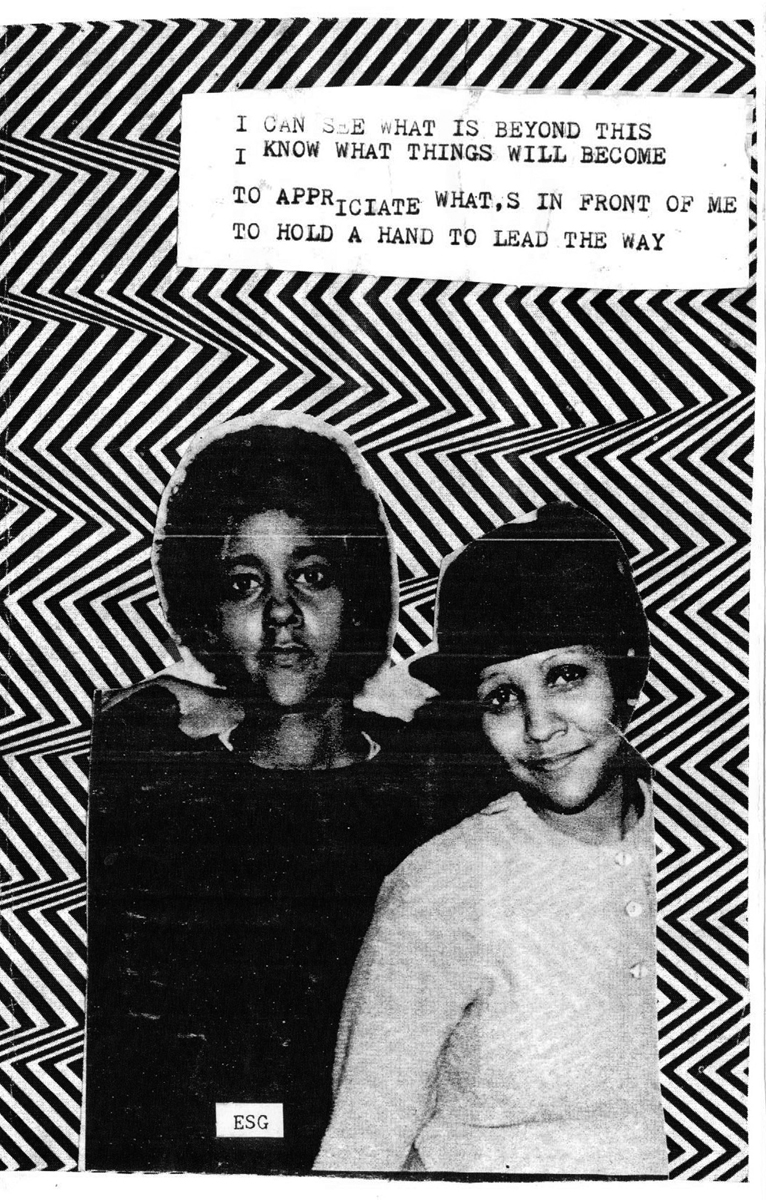

But even beyond the opportunities for visceral nostalgizing, what shines in Shotgun Seamstress for me, even more than in the past, is the great thoughtfulness Atoe takes with interview subjects and delivery of information. The excitement that is woven into the texts. In the scene reports from Portland, which run down full seasons’ worth of shows in short, exuberant bursts. The writing itself, all through each of the zines, has moments of fluorescent breathlessness interspersed with patient, personal vignettes. In the fourth issue, a poem called “Madivinez” by the writer Lenelle Moïse is handwritten in thick black ink, an ode to love, and the limits of language (“I tried / to look up “lesbian” / but the little red book denied / my existence. / I called you, remember?”). Stories of friends and shows and the moments within. An ever-expanding web of black punks reaching for other black punks.

From Shotgun Seamstress, by Osa Atoe. Courtesy the artist / Soft Skull Press.

Shotgun Seamstress, in this form, is also an ode to zines and zine-making, as I understood it in my younger days. The zine was a way to report on your scene, the life you were living where you were. And, due to the transient nature of both scenes and the people in them, zines from many elsewheres might arrive in your hands from some traveling band or some traveling punk. The joke on my scene and ones I orbited was that everyone wanted a zine to represent our chaotic corner of noise, but no one wanted to work on it. To build a zine is a labor of love, and little else. It is a physical practice, complete with paper cuts, glue residue lining fingertips, and the hauling of copies from the print shop back to wherever you housed them.

To see Shotgun Seamstress rendered this way, with so much attentiveness, years after its run, is to see a reciprocation of that labor. A fitting reciprocation, given all that Shotgun Seamstress offered in its time. It was a place where black punks were held with care. As an aging, elder millennial black punk, turning through the pages now still feels as it did before: like a collective gathering of people you maybe knew, musing on things you cared deeply about. Not just Atoe, but all of the writers who contributed to the zine—Adee Licious and Senora Grayson’s guide to traveling around the country for free, via train-hopping and hitchhiking, remains a singular delight. It reads as sort of a condensed, punk version of a green book.

From Shotgun Seamstress, by Osa Atoe. Courtesy the artist / Soft Skull Press.

That guide stands out for how it balances the other gift of Shotgun Seamstress. Beyond history, beyond the dispensary of Black Punk Knowledge and the reporting from the scenes of shows and the extending of a hand toward other black punks, the simplicity of saying I exist, so I know that somewhere, you exist, there’s another reality. The zine, this monument to a scene and a people, also helped black punks survive a scene that could be unkind. Less kind to some of us than others, depending on how identities intersect, or what part of the country one lived in. But the zine was, and remains, a blueprint for survival. Sometimes in the most tactile sense possible—where to go, how to travel, what to avoid. But sometimes just in the small reminders that exist in the interviews, dispatches, and essays. All of them telling black punks that they did not get to their version of here alone. There is a past that echoes with our presence, and a future to be built from it.

Hanif Abdurraqib is from the east side of Columbus, Ohio.