Rumaan Alam

Rumaan Alam

The digital afterlife of a conceptual artist.

It’s generally agreed that the internet is doing something to our brains. We hear phantom alerts. We see filters. We itch for connection, and feel an addict’s pleasure when we achieve it. In ways both obvious and not, technology is changing us. Depending upon the sort of person you are, this will seem either something to celebrate or something to mourn.

I was going to begin by saying that the internet has changed how I think about one of my favorite artists. But I’m not sure whether it’s fair to claim On Kawara as a favorite; a true conceptualist, his art is so cool, so cerebral, all interesting—but still: favorite? Nevertheless, it’s true that Kawara, who died in 2014, is someone whose work I think about often, in part because one of the “people” I follow on Twitter is @On_Kawara.

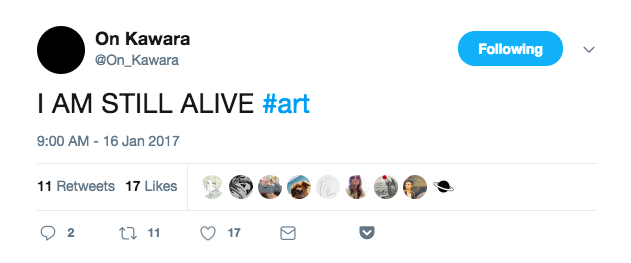

For the past four thousand–odd days, @On_Kawara has issued the same digital proclamation: “I AM STILL ALIVE.” Appended to this message is the statement #art. When you click on that #art, Twitter will deliver every statement so designated, and you see how broad a definition art really has.

@On_Kawara was started by artist Pall Thayer. He doesn’t call himself the project’s author but its maintainer: his role is to ensure the automated flow of daily tweets. I’m in awe of how this little bit of code that Thayer devised has changed my thinking about Kawara.

“I am still alive” is a phrase of Kawara’s; he sent almost nine hundred telegrams bearing that message, over a period of more than thirty years. It’s of a piece with his other long projects, all very interested in the day as a measure of time. Kawara mailed postcards noting the hour at which he arose, mapped his travels, or listed the people to whom he spoke in a twenty-four-hour period, and his Today series of paintings, undoubtedly his best-known project, was simply a rendering of the date on which the painting was made.

Kawara’s lists, maps, and telegrams have the impersonal remove of pure data; the latter, of course, leave the artist out of the equation altogether, a missive dispatched from one clerk to another. The Today series, with its stark white type over solid-colored backgrounds, offers something closer to visual pleasure, a signature, minimalist cool. I’ve long thought about the art as a statement divorced from the man himself. Years ago, I had someone paint me fake Kawaras, depicting the dates of my sons’ births; the artist is so separate from his work it didn’t strike me as a particular insult or violation.

But my steady exposure to the bot has changed how I think about the art. I cannot see a Kawara now without hearing the phrase “I am still alive.” And it’s an apt précis of everything the artist ever did. His abiding preoccupation was the mortal’s desperation to measure time. Kawara’s minimalism and precision once seemed chilly to me; now his entire project seems so touchingly human.

Given our recent history, we must accept that social media has some influence on civic discourse. It makes sense that an aspect of that influence will be curatorial. Some will find this galling, but I find it fascinating, because it’s so hard to predict what work will look right on Instagram or resonate on Twitter. If there is a generation who understands Yayoi Kusama as someone who made beautiful backdrops for selfies, well, at least that generation will remember her.

If you sort Twitter using #art, you can watch as thirteen, eighteen, twenty-five, forty-three people around the world tweet about art. They’re looking at Monet in a museum, joking that their diner grilled cheese is a thing of beauty, showing off a page in their own sketchbook. The critic or consumer accustomed to asking “But is it art?” may someday ask instead if it is “#art.”

I’ve probably spent as many minutes with @On_Kawara as I have in museums actually looking at On Kawara’s work. Of course, with conceptual art, the idea is as important as the image, and authorship seems almost beside the point. If I claim this artist as among my favorites, does it matter if I’m thinking of the unauthorized bot or the man himself or is it simply enough that I am thinking?

Kawara’s telegram series began with three messages: “I am not going to commit suicide don’t worry,” “I am not going to commit suicide worry,” and “I am going to sleep forget it.” This is a bit of context that really shapes how you weigh the fourth, oft-repeated message, “I am still alive.” It can feel like a threat, it can feel like an admission, it can feel despondent, it can feel hopeful.

On Kawara gives us so little of himself that our reading of his words reveals us, not him. In death as in life, the man remains stubbornly unknown. But @On_Kawara distills him to a voice, a direct address no less, liberated from the canvas, from the postcard, from the map.

Among Kawara’s projects were calendars; the most ambitious stretched one million years into the past and one million years into the future. They’re simply pages of dates, a dizzying array of numbers. At the 2015 Guggenheim retrospective, the dates were read aloud as a performance. There’s something similar about @On_Kawara’s tweets. We’re only a few thousand days into it but it’s a short leap to imagine a million tweets, all identical, a litany and maybe a liturgy.

Now that the artist is actually dead, the statement “I am still alive” doesn’t feel plaintive or reflective. Of course, curators and art historians have conferred upon Kawara something close to immortality. But @On_Kawara has given the man immediacy. I now see all of Kawara’s work as the product of a mind fretting over its eventual demise. So too do I see it as the product of a man who triumphed over that demise. He actually is still alive.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novel Rich and Pretty. His stories have appeared in Crazyhorse, StoryQuarterly, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere; his writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the New Republic, and elsewhere. His novel That Kind of Mother will be published in 2018.