Monica Amor

Monica Amor

From the neo-concrete to the culture of the Amazons: A Multitude of Forms looks back at the Brazilian avant-gardist.

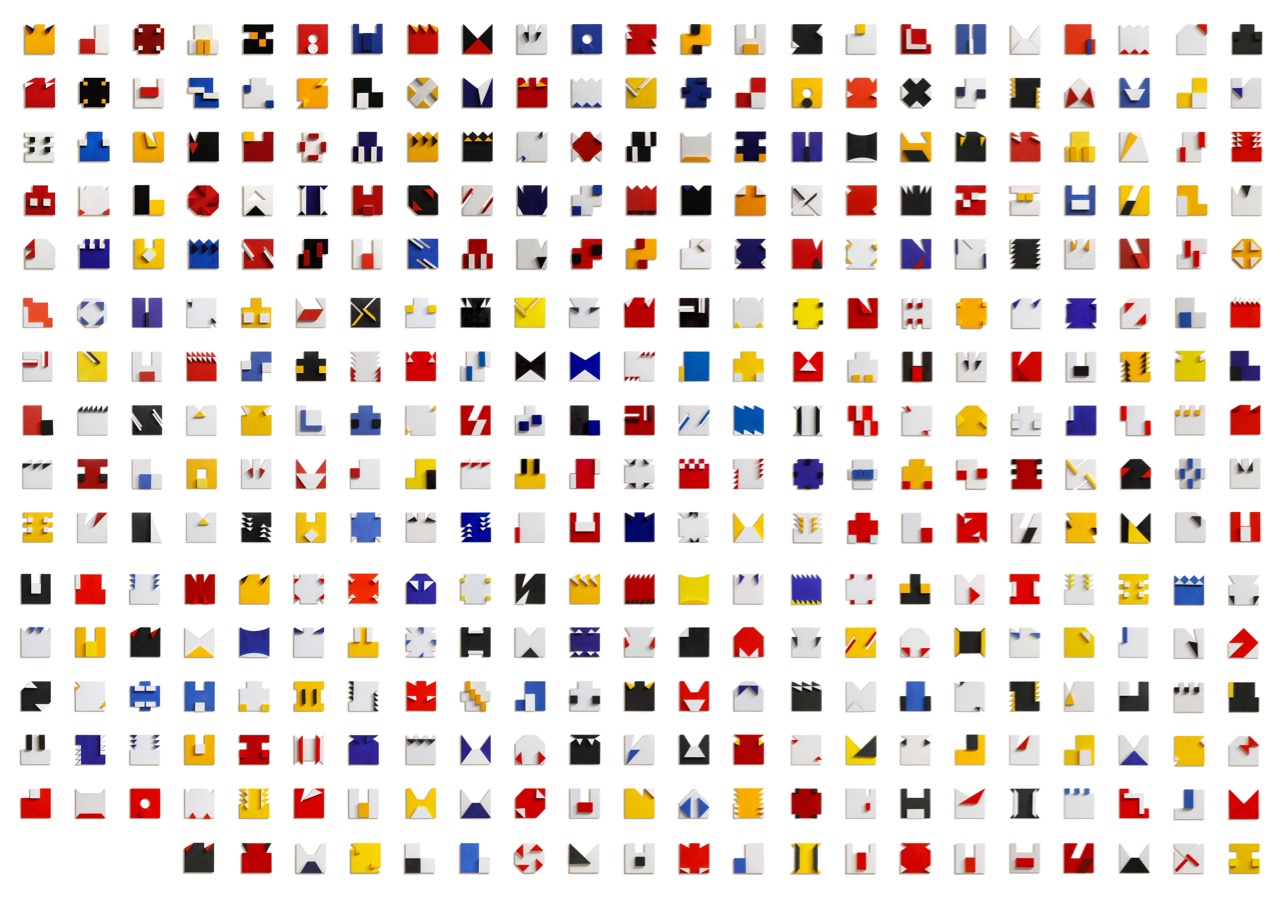

Lygia Pape, Livro do tempo (Book of time), 1961–63. Tempera and acrylic on wood, 365 parts. Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms, Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York City, through July 23, 2017

• • •

The Met Breuer’s ambitious retrospective of Lygia Pape (1927–2004)—her first US museum survey—offers a unique opportunity to take a deep dive into the pioneering Brazilian modernist’s oeuvre. It also sets some intriguing art historical stakes, challenging established narratives that marry Pape’s work to that of her better-known countrymen, Lygia Clark and Helio Oiticica—fellow members of the neo-concrete movement. Formed in Rio de Janeiro in 1959, the group aimed to refashion geometric abstraction by liberating the work of art from the frame or the pedestal and bringing it into the space of the everyday. Like Clark and Oiticica, Pape began by producing sculptural reliefs and two-dimensional works during an initial period of fertile experimentation, and by the end of her career was creating pieces that directly involved the body of the artist and/or those of her viewers. But as this exhibition illustrates, her path along the way diverged from that of her close colleagues.

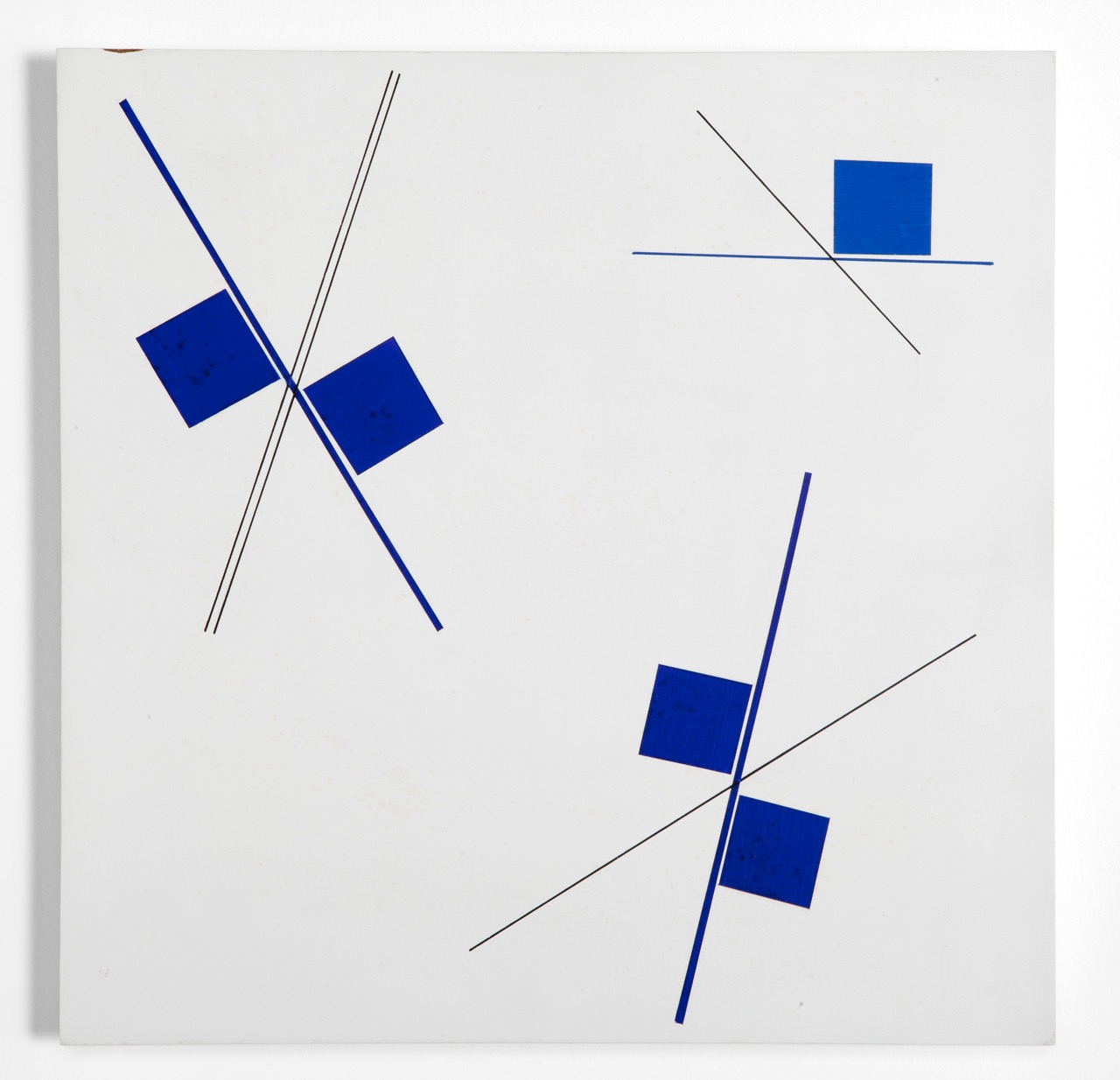

Lygia Pape, Pintura (Painting), 1954–56. Gouache on fiberboard. Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

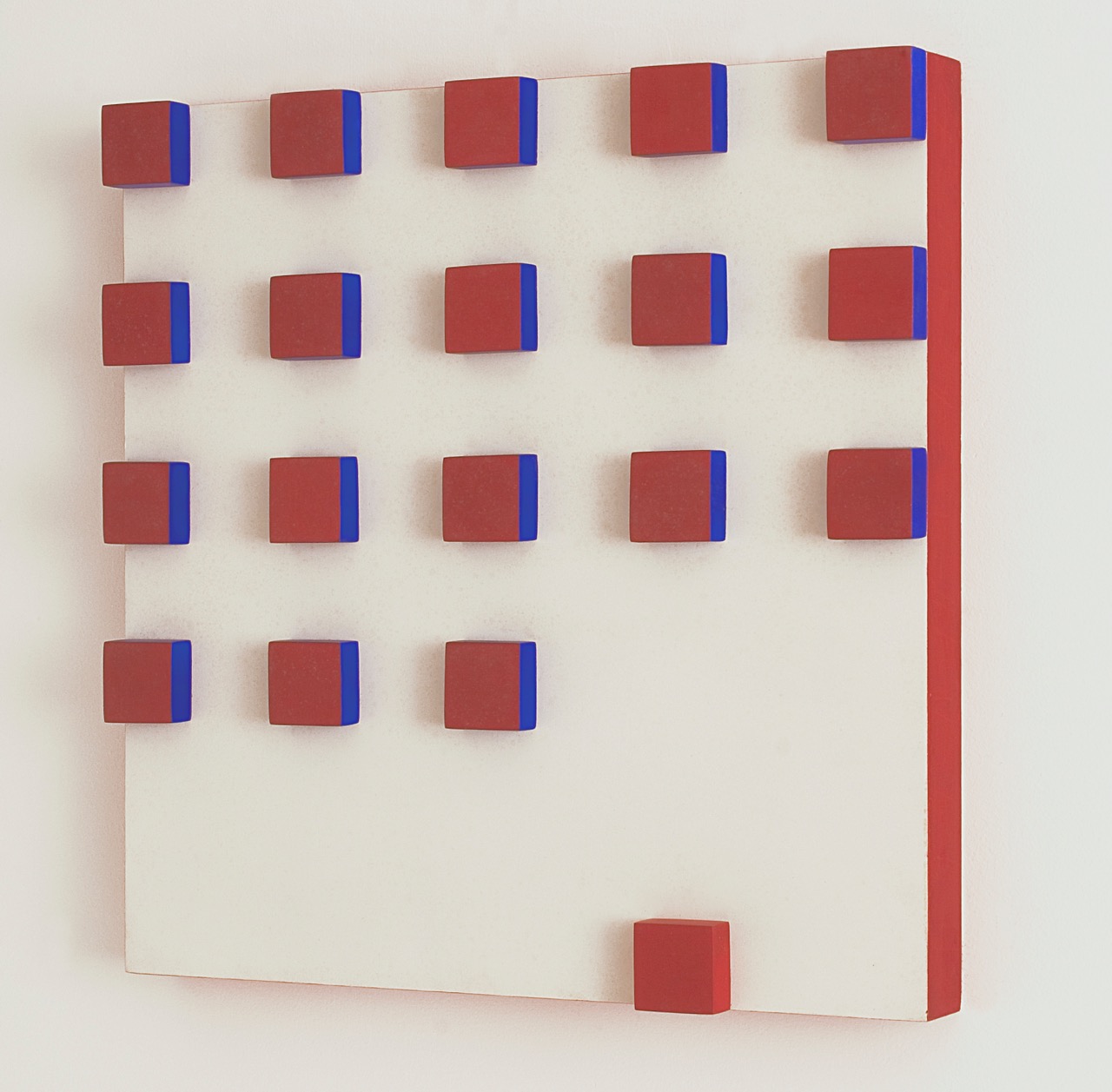

The show is organized chronologically, and deftly balances the many aspects of Pape’s practice. The first gallery presents a wall of early gouaches on fiberboard that attest to her fluency in the geometric vocabulary privileged by the neo-concretists. These compositions from 1954 to 1956 are colorful and dynamic, revealing an intuitive approach to shape and line that signals the influence of Swiss concrete art, which was exhibited at the first São Paulo Biennial in 1951. This gallery also features beautifully installed square wall reliefs with geometric shapes painted in a Mondrianesque palette of white, black, and primary colors protruding from predominantly white backgrounds. Relief proved instrumental for these artists—especially Clark and Oiticica—as it facilitated a transition from the static realm of the wall to the performative realm of the body.

Lygia Pape, Relevo (Relief), 1954–56. Gouache and tempera on fiberboard on wood. Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

For Pape, though, that transition was less direct, as from 1955 to 1960 she pursued a dedicated exploration of line and texture in drawings and woodcuts. These thoroughly two-dimensional works, primarily executed on Japanese paper, play with linear repetition, symmetry, and the role of negative space in the production of form. The woodcuts, which the artist retrospectively called Tecelares (Weavings) sometime between 1979 and 1983, have been discussed as investigations of ambiguous space (by rejecting traditional figure/ground relations), and in terms of a mode of spectatorship that unfolds over time—both paramount concerns of the neo-concrete manifesto. Indeed, these prints have been hailed as the climax of Pape’s neo-concrete contribution. But the centrally organized composition Pape favored subtly activates the viewer’s sense of the image’s frame, that is to say, the thing that separates the space of art from the space of the world. It is precisely this distinction that Clark and Oiticica sought to overcome.

Lygia Pape, Tecelar, 1960. Woodcut on Japanese paper. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

Rather than engaging neo-concretism’s injunction to vanquish the pictorial plane, these prints stress the materiality of the surface. This of course corresponds to the process of physically imprinting the woodblock onto the paper—the traces we see thus favor the tactile as opposed to the optical. This oneness of material, technique, and form seems to have provided rich ground for Pape to reject individual expression while accentuating texture to repress the virtual space of the white plane. The figure of weaving the Tecelares invoke suggests that the traces of the woodblock are interwoven with the paper like the weft and warp of a textile.

Lygia Pape, Livro da arquitetura (Book of architecture), 1959–60. Tempera on cardboard, 12 parts. Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

In an adjacent gallery, the Book of Creation and the Book of Architecture (both 1959–60) also deal directly with their own materiality. Here, on cardboard pages measuring approximately twelve by twelve inches each, various techniques (collage, cutouts, origami-like folds) produce abstract images symbolizing themes of space and figures of origin. Facsimiles of the unbound folios are available to viewers in the exhibition; as if paging through an interactive pop-up book, visitors can manipulate the boards in the order of their choosing, thus disrupting the traditional linear temporality of reading and bridging the divide between viewer and art object.

Lygia Pape, Roda dos prazeres (Wheel of pleasures), 1967. Porcelain vessels, droppers, distilled water, flavorings, and food coloring. Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

After a hiatus in the sixties, when Pape designed title credits for experimental filmmakers and worked as a graphic designer for a Brazilian food company, she came back to the visual arts with a practice that rejected object-making and the confines of the museum. With a new focus on the body, Pape organized performative actions at the margins of the city (beach, favela, parks). At the Met, pristine reconstructions or recently filmed versions of these actions eclipse the charged political moment in which Pape was working. Her commitment to occupy public space during this period is thus decontextualized, and remains largely untheorized in the exhibition. Though the curators do make an effort to provide some of the far-grittier documentation of original performances, other works (like Wheel of Pleasures [1967], a circle of bowls containing flavored liquids tinted by food dye that the artist would taste alongside her viewers) look like decorative objects rather than performative devices. The museum’s invitation to interact with Wheel of Pleasures on specific days does not alleviate this problem, which points to the larger issue of how to present works of a participatory, public nature in a museum context.

Lygia Pape, Ttéia 1, C, 1976–2004, reconstructed 2017. Golden thread, nails, wood, and lighting. (Prior installation view.) Photo: Paula Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape.

Pape’s turn to performance in public space was followed by a series of videos and photographs documenting the native populations of Brazil, their traditions and environments. Next to these pieces, a large-scale installation of golden threads and dramatic lighting titled Ttéia 1, C (Web 1, C), conceived in 1976 but only realized in 2002, produces a dematerializing effect accentuated by the all-black space that houses the installation. It is a dramatic counterpoint to the obdurate materiality of Pape’s prints, but it sits oddly next to her anthropological and sociological work of the time. Her last sculptures, Amazoninos (1989–92), exhibited at the very end of the show, clearly attempt to synthesize Pape’s lifelong interest in abstraction with her commitment to foregrounding the culture of the Amazons. However, these iron works, consisting of abstract elements extending from a flat surface and painted in solid colors, are rather ornamental and fail to convey the complexities of these two distinct veins of inquiry. In the end, for unfamiliar viewers, the varied concerns that weave throughout Pape’s practice may feel unresolved here, raising more questions than the curators can answer in this format. The exhibition is a rich overview of the artist’s rigorous and compelling oeuvre—but also a reminder of the scholarship that still remains to be done on this acutely important artist.

Monica Amor is a professor of modern and contemporary art at the Maryland Institute College of Art. She writes and lectures regularly on postwar and contemporary art with special attention to interdisciplinary practices and the dynamics of global modernity. She is the author of Theories of the Nonobject: Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, 1944–1969 (University of California Press, 2016) and is currently writing on Philippe Parreno’s work. Her next book project is entitled Gego: Weaving the Space In-Between.