Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

From personal family dramas to provocative humor: an expansive range of films by the boundary-pushing collaborators.

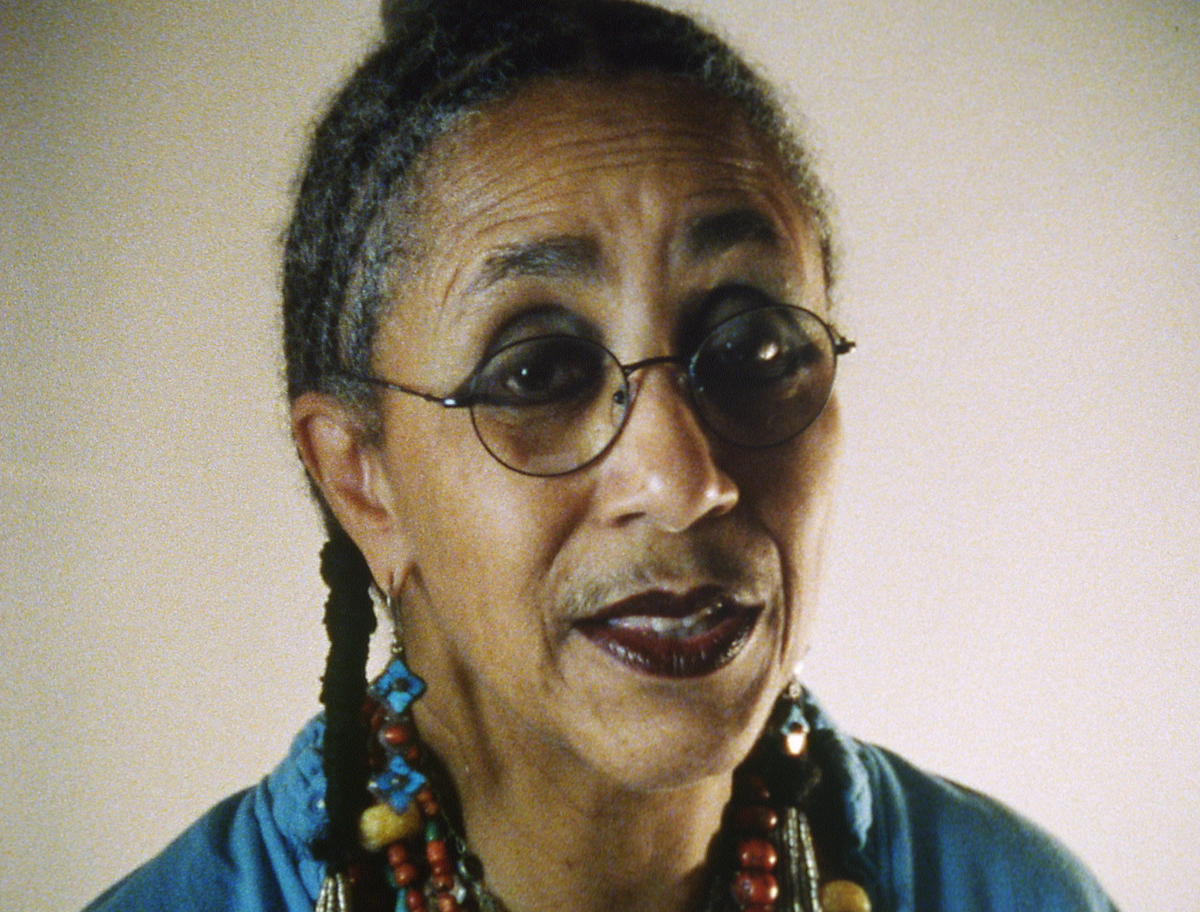

Still from The KKK Boutique Ain’t Just Rednecks. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

“A String of Pearls: The Films of Camille Billops and James Hatch,” Brooklyn Academy of Music, 30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn,

February 3–9, 2023

• • •

The six films that Camille Billops made with James Hatch, her longtime partner in love and creative pursuits, are usually classified as documentaries. The term seems too inadequate, though, for works that traverse so much psychic territory in so little time (all but one title in this sextet run under an hour). Racism, family trauma, shame, and taboos are the abiding themes in these movies—harrowing subjects often leavened by humor, whether that of the filmmakers or their subjects. “We’re border-crossers,” Billops says, while cutting Hatch’s hair in a field of sunflowers, in The KKK Boutique Ain’t Just Rednecks (1994). The declaration reflects not only the porous nature of their nonfiction moviemaking but also the strenuously guarded lines of propriety—regarding motherhood especially—they endeavored to explore.

Still from The KKK Boutique Ain’t Just Rednecks. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

When Billops made that statement, she and Hatch had been together for more than thirty years (they married in 1987); their relationship ended only with her death, in 2019, at age eighty-five (he died the following year, at ninety-one). They met in 1959 in Los Angeles, where she was born in 1933 to parents who were among the millions of African Americans who left the South in the Great Migration. At the time of their first encounter, she was a single mother with a toddler daughter (more on her in a moment), working full-time in a bank, finishing her college degree, and embarking on an art practice. Married with two children, Hatch, a white Iowan born in 1928, was teaching in the theater department of UCLA. (Billops’s stepsister, who was in the cast of a musical about civil rights that Hatch had cocreated, introduced them.) By the mid-’60s, Hatch was divorced from his first wife and he and Billops were living in New York, he as a faculty member at City College specializing in the history of Black theater and she as a ceramicist, printmaker, and painter increasingly invested in art and activism. (Two of Billops’s pieces are currently on view at MoMA’s Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces exhibition.)

Still from A String of Pearls. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

A SoHo loft Billops and Hatch purchased in 1973 quickly became an essential meeting place and salon for a multiracial circle of artists, writers, and performers. In this sprawling space the couple amassed the Hatch-Billops Collection, a trove of materials related to Black culture, and published Artist and Influence, an annual journal, begun in 1981, featuring interviews with (primarily) Black visual and performing artists of multiple generations. Their shift to filmmaking, in the late ’70s, seemed inevitable for such a boundlessly curious and energetic duo. “Film was just another art form, just different material,” as Billops told an interviewer in 1992.

Still from Take Your Bags. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Billops and Hatch share directorial credit on five of their six films; the short Take Your Bags (1998), for which she is the sole auteur, finds Billops wryly riffing on slavery and cultural theft to an exceptionally attentive little boy, a distant relative of hers. Despite this joint authorship, Billops was the catalyst behind many of their works, which often draw upon her own family’s history and frequently feature her—a vivacious figure with elaborate eye maquillage and a strip of hair above her upper lip—in front of the camera. Suzanne, Suzanne (1982), their first film, centers on Billops’s niece, who matter-of-factly recounts her past heroin addiction, her multiple arrests, and the merciless physical abuse she endured from her father, dead since 1968. Suzanne is not the only one interviewed; Billops extends her inquiry to Suzanne’s older brother, Michael, and especially to her mother, Billie (Billops’s older sister), who recalls the “relief” she felt after her husband died but who had done little to stop him from beating their child. In this gutting film’s most wrenching segment, shot in high-contrast black-and-white, mother and daughter take part in a restorative-justice tableau: Suzanne, in the foreground, with her eyes cast downward, calmly asks her mom why she didn’t intervene—an interrogation that causes Billie, seated directly behind her child, to break down into a very real torrent of tears. (Two decades after this inaugural effort, Billops and Hatch would turn their attention to the respective sons of Michael and Suzanne in A String of Pearls, investigating how these now twentysomething men approached the responsibilities of young fatherhood.)

Still from Suzanne, Suzanne. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

The far more ebullient Older Women and Love (1987), inspired by an aunt of Billops’s who had a much younger boyfriend, surveys several ladies north of forty who have likewise enjoyed (or were then currently enjoying) May-December romances. Interspersed throughout the tonic, candid assertions of the interviewees (“A fine, taut, thin male body moves me”) are staged segments spotlighting Billops at a gossipy gathering; among the guests delighted by her tea-spilling is George C. Wolfe, the renowned playwright and director then in the ascendant phase of his career (he also pops up in two later Billops-Hatch films).

Still from Older Women and Love. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Another partygoer eager to dish with Billops in those scenes is the young woman who would be the focus of the best-known title in the Billops-Hatch corpus, Finding Christa (1991). Christa Victoria is the daughter Billops gave up for adoption in 1961, when the child was four; in 1981, and now an aspiring singer, she sent Billops a cassette with an original composition, the lyrics explaining why she’d like to be reunited with the woman who relinquished her. As she did in Suzanne, Suzanne, Billops elicits the memories of relatives and friends in Los Angeles, asking them questions—“Do you feel I was justified in giving her up?”—they are sometimes reluctant to answer. Billops herself remains unrepentant (“I’m very sorry about her hurt. But I’m not sorry about the act”), stressing that Christa fared infinitely better with her adoptive family (whose loving matriarch is another talking head) than she ever would have under her care. For her part, Christa seems sanguine, dreaming of the day that she’ll perform for a “stadium of 50,000 people” eager to hear her “life songs.”

Still from Finding Christa. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Yet unlike Suzanne, Suzanne (for which Christa and Billops duet on the title song), there is no raw, cathartic moment between the two women. They appear together in fantasy sequences or stilted reenactments that are notable only for their odd tension. Those uneasy dynamics continued offscreen—Billops barred Christa from attending the Sundance awards ceremony where Finding Christa was given a top prize—until the younger woman’s death in 2016, three years after Billops had cut off all communication with her.

Still from Finding Christa. Courtesy the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

But a kind of bizarre onscreen abreaction does take place in The KKK Boutique. One of the more astonishing sequences in that project—which Hatch describes in voice-over as “a docu-fantasy about the ways that racism changes our souls” and is a clear forerunner to the satirical outrages of Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000)—shows Christa peddling dolls of different races like a hot dog vendor at a ball game. “Pick a baby, any baby,” she croons, before asking a group gathered around her, “What baby would you adopt?” In that scrum stands Billops. She makes a lot of noise, deflects the question—a way of admitting, perhaps, to a great wound she inflicted, the fallout from which she continued to suffer.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.