Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Into the dark: director Tsai Ming-liang’s elegy for moviegoing.

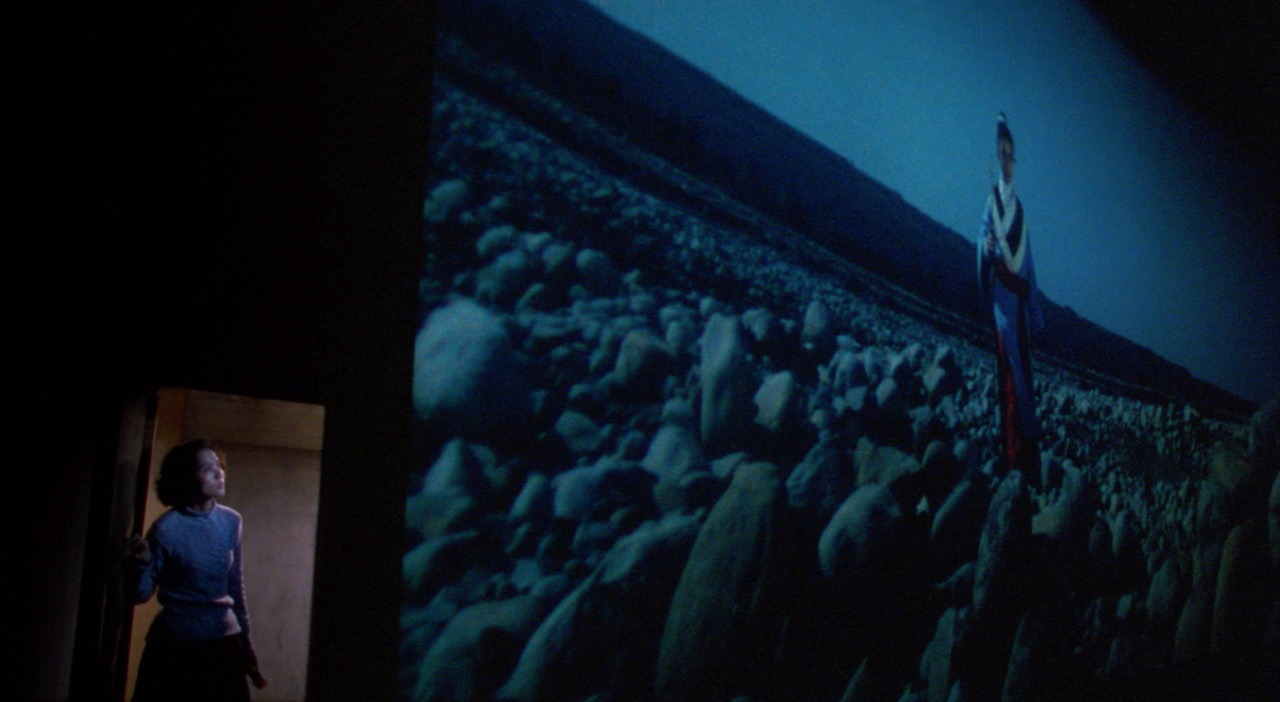

Chen Shiang-chyi as the ticket taker in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Courtesy Metrograph Pictures.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn, written and directed by Tsai Ming-liang, available to watch via Metrograph

• • •

“No amount of mourning will revive the vanished rituals—erotic, ruminative—of the darkened theater,” Susan Sontag wrote in “The Decay of Cinema,” an essay published in 1996. That keening has only grown louder over the past quarter century. It’s been especially pronounced ever since March of this wretched year, of course, when movie houses throughout the country shuttered; many may never reopen. In a gesture both plaintive and pleasingly perverse, the Manhattan-based Metrograph presents, via its virtual cinema, a new 4K restoration of one of the most melancholy films about moviegoing: Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), a playful, minimalist dirge that reminds us of the sublimities and absurdities of a practice that for some has been a pastime, for others a calling.

The film is set in the Fu-Ho Grand Theater, an actual bunker-like cinema, then perilously close to bankruptcy, on the outskirts of Taipei. (Tsai had shot a scene for his previous feature, 2001’s What Time Is It There?, in the movie house.) The prologue of Goodbye, Dragon Inn imagines the theater in better days: curtains blowing at the back of the auditorium reveal a nearly sold-out crowd raptly, reverently watching Dragon Inn, the 1967 wuxia triumph directed by King Hu. In just a minute or two, the brief opening segment potently calls to mind a passage from Roland Barthes’s 1975 essay “Leaving the Movie Theater,” which extols the subsidiary marvels of cinemagoing, a process that involves “letting oneself be fascinated twice over, by the image and by its surroundings—as if I had two bodies at the same time: a narcissistic body which gazes, lost, into the engulfing mirror, and a perverse body, ready to fetishize not the image but precisely what exceeds it: the texture of the sound, the hall, the darkness, the obscure mass of the other bodies, the rays of light, entering the theater, leaving the hall . . .”

Chen Shiang-chyi as the ticket taker in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Courtesy Metrograph Pictures.

Those secondary pleasures still exist, even if in significantly diminished form, during the event on which Tsai’s film is centered: a final screening of Dragon Inn on the last night that the Fu-Ho is open for business. (The theater closed down in 2002 after thirty years, shortly after Tsai completed filming.) No more than ten spectators are to be found in any of the roughly three hundred slightly tatty carmine seats. One of them, an unnamed young man (Kiyonobu Mitamura), who we later learn is a Japanese tourist, has escaped the pouring rain—a common element in Tsai’s water-logged oeuvre—and taken a seat midway through Dragon Inn. Several rows down sits a little boy, momentarily unattended and blissfully absorbed with his bag of candy. Meanwhile, the ticket taker (Chen Shiang-chyi), a forlorn woman with an iron brace on her right leg, sips tea and takes small bites from a large pink steamed bun in her tiny office. She’ll slice a chunk of that delicacy, lovingly wrap it, and leave it upstairs for the only other employee at the Fu-Ho that night, the projectionist, played by Tsai’s signature actor, Lee Kang-sheng.

Lee Kang-sheng as the projectionist in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Courtesy Metrograph Pictures.

Unhurried and composed of long, static takes, Goodbye, Dragon Inn alternates between the action within the auditorium and that in the warrens, staircases, and hallways outside it. Inside the theater, the Japanese visitor cruises—his hard stare at a middle-aged gent never returned—and rebuffs the overture of another like-minded spectator. These carnal, comic pursuits occur elsewhere in the Fu-Ho: in the men’s room, here transformed into an exquisitely framed tableau in which three men stand for eternity at the urinals, each hoping someone else will make the first move; and in a storage area of the theater, so cramped with boxes that the sex-searchers barely have room to squeeze past one another, physical proximity that paradoxically seems to dispel rather than expedite lusty action.

During this awkward roundelay, the first line of dialogue is spoken, occurring about halfway through Goodbye, Dragon Inn’s eighty-two minutes: “Do you know that this theater is haunted?” All cinemas, Tsai’s movie suggests, are shrines to the supernatural—places, at once holy and profane, where we commune with the outsize phantasms shimmering before us. Or, to quote Sontag again, “Movies resurrect the beautiful dead.” A tweak on that aphorism is borne out when we discover that two attendees at the Fu-Ho’s final screening are Shih Chun and Miao Tien, actors in King Hu’s opus who behold their younger selves onscreen. We watch them watching, a profoundly moving moment as the camera remains tight on Shih’s face. Shadows and light play across his visage, tears slowly form in his eyes, and he breaks into a slight smile.

Yang Kuei-Mei as the peanut-eating woman in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Courtesy Metrograph Pictures.

Although just a handful of people speak no more than a dozen lines in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, Tsai’s film is dense with sound, not least the slurping and crunching of aggressive snackers in the audience—aural gags that are supplemented by expertly timed visual ones, like the two bare feet that suddenly materialize and rest on top of a seat immediately behind the Japanese guy. The aural harshness is balanced by a more harmonious musique concrète, such as the whir of a film projector and the various muffled registers of Dragon Inn as it’s heard throughout the Fu-Ho.

Chen Shiang-chyi as the ticket taker in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Courtesy Metrograph Pictures.

All of these stimuli, all of these annoyances, all of these delights are possible only when we take the risk of sitting in the dark with people unknown to us—an adventure that most of us won’t be able to resume for an uncertain number of months. I first saw Goodbye, Dragon Inn in the fall of 2003 on the enormous screen of the Walter Reade Theater during the press screenings for the New York Film Festival. Revisiting it seventeen years later on a laptop while seated at my desk in the living room, I thought of another line from Barthes’s essay, with “the device” supplementing “television”: “In this darkness of the cinema . . . lies the fascination of the film (any film). Think of the contrary experience: on television, where films are also shown, no fascination; here darkness is erased, anonymity repressed; space is familiar, articulated (by furniture, known objects), tamed: the eroticism . . . the eroticization of the place is foreclosed: television doomed us to the Family, whose household instrument it has become—what the hearth used to be, flanked by its communal kettle.” I long for the day when I can once again be flanked by a stranger’s unshod feet.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.