Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

“You have the grace”: in Olivier Assayas’s 1996 metamovie, a radiant Maggie Cheung.

Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Irma Vep, written and directed by Olivier Assayas, available to stream on the Criterion Channel and HBO Max

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that movie theaters in New York City, where 4Columns is based, and other cities throughout the US remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

Some movies transport me to such states of delirium that I am driven to see them multiple times in the same week. One of these exhilarating films happens to be about moviemaking itself: Olivier Assayas’s sinuous, kinetic, waggish Irma Vep, which opened at Manhattan’s Film Forum on April 30, 1997, eight months after my arrival to the city. I was a graduate student then, with obscene amounts of free time—a schedule conducive to my cine-gluttony. There were so many gaps in my pitiful film knowledge; I had so much to see and discover. An oblique, supremely enjoyable course in movie history, Irma Vep, Assayas’s sixth feature, not only helped fill in some of those lacunae but also acquainted me with the writer-director, whose oeuvre I would assiduously study.

The movie also marked my introduction to performers who completely besotted me, chief among them Maggie Cheung, for whom Assayas expressly wrote the project. (They first met in 1994, at the Venice Film Festival.) The actress plays a version of herself: a superstar of Asian cinema, here cast by René Vidal (Jean-Pierre Léaud)—a desiccated, unstable auteur, decades removed from his initial triumphs—in the lead role of his bedeviled reimagining of Les Vampires, the famed Louis Feuillade serial from 1915 that starred mononymed legend Musidora as Irma Vep, a cabaret singer involved in a crime syndicate.

Maggie (or should that be “Maggie”?) is first seen entering a shambolic, fractious Paris film office, having just arrived off a twelve-hour flight from Hong Kong. Amid the squabbling of the bumptious production managers and various other crew members on Vidal’s remake, Cheung emits a serene, celestial glow. Assayas once described the actress as “an up-to-date version of an old-fashioned movie star”; never dimming, her preternatural radiance, her extraordinary ability to bring the past to the present and vice versa, is the quality that links her most strongly to big-screen divinities of yore. (Another metamovie, Stanley Kwan’s Center Stage, an unconventional biopic from 1991 about Ruan Lingyu, a silent-screen goddess of prerevolutionary Chinese cinema who killed herself in 1935, also showcases Cheung’s talent for inhabiting different temporalities: she plays herself, Ruan, and the characters the icon performed.)

Jean-Pierre Léaud as René Vidal in Irma Vep. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Much of the chaos surrounding Irma Vep’s film-within-the-film stems from René’s tenuous mental health. That this faltering filmmaker is played by Léaud, who, having made multiple movies with François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, stands as the most paradigmatic actor of the Nouvelle Vague, signals Assayas’s sly humor about French cinema’s putative decrepitude. Though only in his early fifties when Irma Vep was made, Léaud looks a hundred years older. Yet René, no matter how prone to tantrums, isn’t the butt of an easy joke; by the end, he emerges as something of a valiant figure, proving himself to be an avant-garde genius. Léaud, for his part, brings to the fore his character’s indestructible dignity; beneath René’s outsize outbursts lies pathos, not buffoonery.

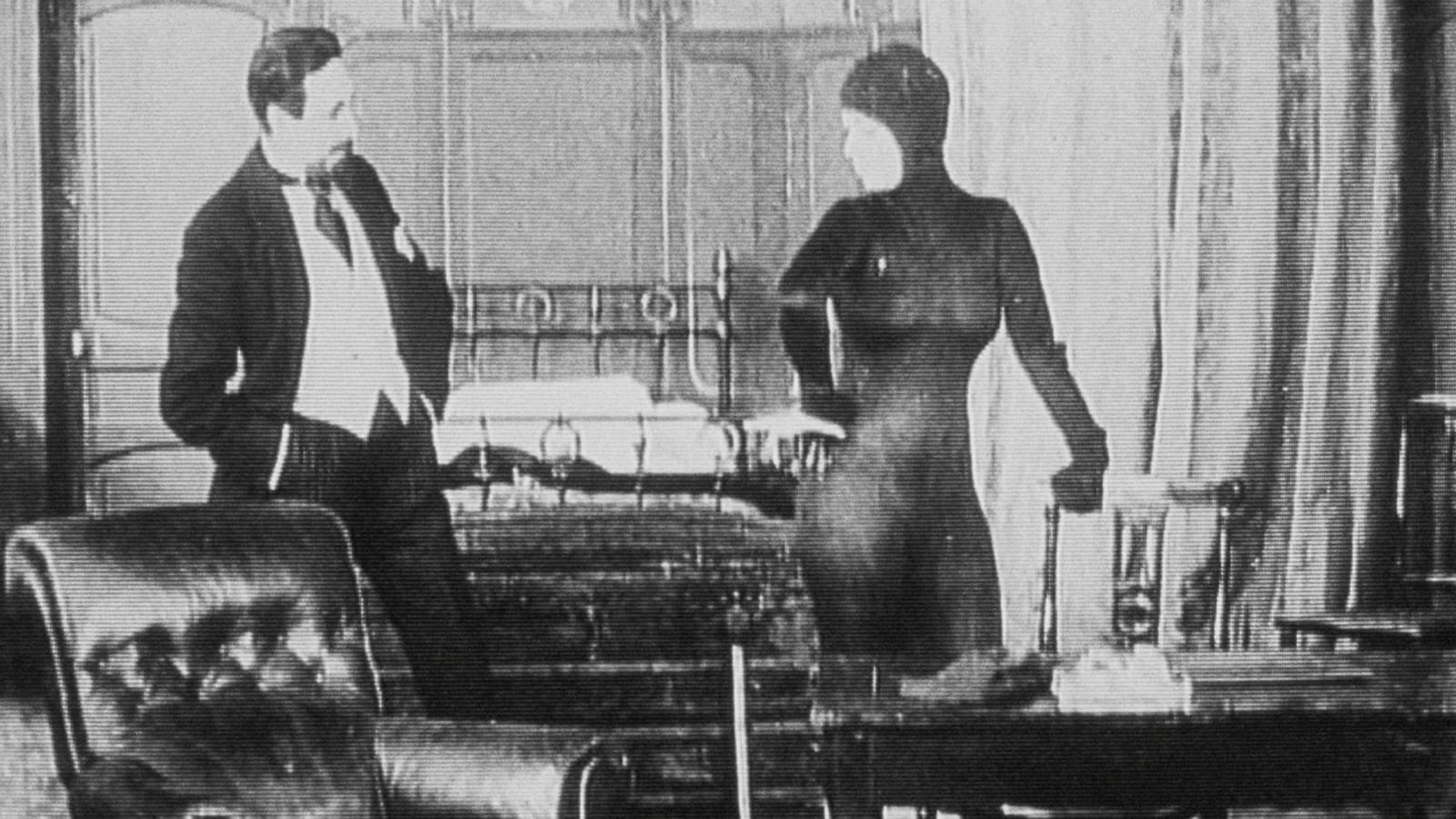

Musidora (right) as Irma Vep in Les Vampires. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

The easily agitated filmmaker, always impeccably dressed in scarves and herringbone blazers, seems most at ease when discussing his redo of Les Vampires with Maggie, who is committed to her director and appears to be the only one among the cast and crew who wants to go about their work calmly and efficiently. “You can be Irma Vep because you have the grace,” René tells his star, in thickly accented, often unintelligible English, after they watch a clip from a DVD of The Heroic Trio (1993), Johnnie To’s wuxia marvel in which Cheung plays a chopper-riding bounty hunter—one of many HK action films starring the actress littering René’s living-room floor. To further prove his point, he inserts a VHS tape of Feuillade’s original, cued to a scene of Musidora clad in her most infamous costume, a full black bodysuit and balaclava; surely the woman we’ve just seen execute midair leaps and flips (even if done by stunt doubles, as Maggie is quick to point out) on René’s TV can update the feline theatrics of the silent-film star.

But first, Musidora’s outfit will need to be modernized, a task that occasions one of Irma Vep’s funniest segments: a trip to a sex shop where Maggie, trying on various latex catsuits and fetish wear, will be fussed over by tetchy costume designer Zoé (Nathalie Richard, another actress I first encountered in Irma Vep with whom I would develop an ongoing fascination). Always in a state of high dudgeon with her French coworkers, Zoé seeks to allay Maggie’s doubts about the kinky getup (“Are you sure this is what René wants?”), delivering this charmingly consonant-elided assurance about the director’s vision: “If he wants ’ooker, I say it’s okay.”

Nathalie Richard as Zoé and Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Zoé, like many others involved in the remake of Les Vampires, is smitten with Maggie; in the same way, Irma Vep clearly reveals Assayas’s enchantment with Cheung. (They were married briefly, from 1998 to 2001, splitting amicably. They made one more movie together, 2004’s Clean, in which Cheung, in her last major film role to date, plays a woman struggling to kick her dope habit, get her life together, and reclaim her young son.) And, as several of her colleagues do, Zoé casts her aspersions on René’s project—“It’s been done. Why do it again?”—if not all Gallic cinema. (What would Zoé have made of Assayas’s announcement earlier this year that he’s adapting Irma Vep into an eight-part TV series?) This internalized Francophobia is most piquantly on display during an on-set interview Maggie endures with a young TV journalist who yaps effusively about John Woo and Arnold Schwarzenegger before declaring his country’s cinema “a crypt” and “only for the intellectuals.”

Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep. Image courtesy Criterion Collection.

Maggie’s response to this inane dichotomy evinces her lucidity: “I think there are different audiences for different films. And there’s nothing wrong with that.” This exchange would be mirrored nearly two decades later in Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), another supple, immensely intelligent, ingeniously casted metamovie animated by questions about the state of cinema itself. The later film pairs Juliette Binoche, playing Maria Enders, a middle-aged, internationally acclaimed actress—a character not too far removed from Binoche herself—with Kristen Stewart, who had then recently completed the Twilight series, as Valentine, Maria’s dutiful but strong-willed assistant. Maria, who’s decided to drop out of the latest X-Men installment, has grown increasingly cynical about the movie industry. But Valentine delivers several eloquent defenses of the big-budget cinema her boss denounces—the well-reasoned rejoinders pleasingly emerging from a young woman who, IRL, had starred in one of the most successful movie franchises of all time.

I had a much more demanding schedule in 2015, when Clouds of Sils Maria opened theatrically, than I did as a wastrel graduate student. But I still couldn’t resist seeing it twice in one week.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.