Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Thirty years after his death, the photographer gets the biopic treatment.

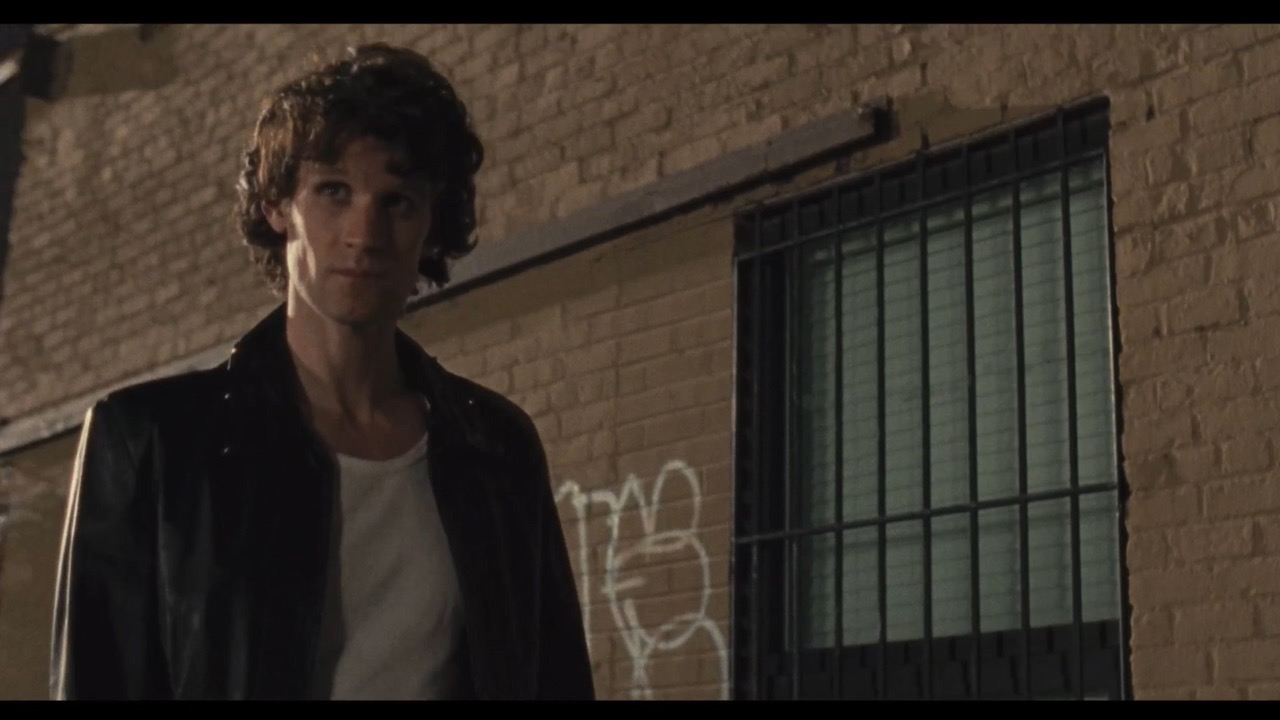

Matt Smith as Robert Mapplethorpe in Mapplethorpe. Image courtesy Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Mapplethorpe, directed by Ondi Timoner, opens March 1, 2019, in

New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago

• • •

The word perfect often has often been yoked to the work of Robert Mapplethorpe, whose black-and-white photos, whether of extreme S-M tableaux, flowers, or celebrities, are defined by the satiny elegance of classic modernism. The Perfect Moment was the name of the traveling exhibition that opened in 1988, just a few months before the photographer died, at age forty-two from AIDS-related complications, and which became a flash point in the culture conflagration that raged during the Reagan and Bush I eras. In 2016, the Getty and the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art cohosted Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium. Now he is the subject of that most imperfect of art forms: the biopic.

Ondi Timoner’s wobbly Mapplethorpe is the first docudrama devoted to one of the most significant artists of the second half of the twentieth century, a luminary who has already been the focus of two earlier documentaries: James Crump’s Black White + Gray: A Portrait of Sam Wagstaff and Robert Mapplethorpe (2007), which centers on the photographer’s crucial relationship, begun in 1972, with the older curator and collector; and Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato’s cradle-to-grave chronicle Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures (2016). In between these films, Patti Smith’s tender memoir Just Kids (2010) recounted her romance and friendship with Mapplethorpe, whom she met in 1967, when they were penniless and unshakeable in their commitment to their art.

Matt Smith as Robert Mapplethorpe in Mapplethorpe. Image courtesy Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Like many biopics, Mapplethorpe is frequently leaden, if not superfluous, given how extensively the artist’s brief, incandescent existence has been cataloged over the past decade-plus. A hint of branding opportunism attends to the release of Timoner’s movie, which premiered last year at the Tribeca Film Festival: Mapplethorpe marks a gruesome anniversary, bowing in theaters almost thirty years to the day of the photographer’s death, on March 9, 1989, and coincides with the Guggenheim’s recently opened Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now (reviewed by Ed Halter in 4Columns two weeks ago).

Made with the support of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Timoner’s project is filled with explicit tensions—specifically, those between still and moving images—a contrast that has the effect of undermining the very premise of a biopic: to dramatize, with some authority, pivotal scenes from a life. Throughout Timoner’s film, photographs by Mapplethorpe (and a few of him taken by others) pop up on screen, their formal rigor and beauty highlighting the movie’s obviously limited budget—and its limited imagination. (Seemingly hardest hit by this lack of funds was Mapplethorpe’s wig department.) The stark juxtaposition between static archival record and reenactment jumps out instantly: an opening montage of photos of the real Mapplethorpe, beginning with his boyhood in Floral Park, Queens, and culminating with him as a young man, sometime in the late 1960s, bedecked in a ROTC uniform, segues to the actor portraying him—Matt Smith—wearing that same military outfit and pacing a room, smoking. For the next one hundred minutes, as we follow the photographer’s ascendance to his demise, segments of Smith-as-Mapplethorpe first wielding a Polaroid SX-70 camera and then a Hasselblad 500 are augmented by a fleeting portfolio of the real pictures those respective sessions yielded.

Matt Smith as Robert Mapplethorpe in Mapplethorpe. Image courtesy Samuel Goldwyn Films.

By insisting on drawing the spectator’s attention to the actual and the simulation, Timoner—who’s made several documentaries, including We Live in Public (2009), a shallowly conceived gloss on privacy and surveillance, and who cowrote Mapplethorpe, her narrative-feature debut, with Mikko Alanne—places an undue burden on Smith, a British performer best known for his work in television (Doctor Who, The Crown). Physical resemblance to the central personage isn’t a requirement for a successful biopic, but it doesn’t help that Smith often calls to mind the sexless Crispin Glover. Rarely do we sense the dark erotic allure that Mapplethorpe, memorably described by Fran Lebowitz in Bailey and Barbato’s documentary as looking “like a ruined Cupid,” held for his lovers, models, and muses (who were often one and the same).

Also miscast is Marianne Rendón as Patti Smith. Too femme and sporting one of the film’s ghastliest perukes, the actress evinces none of the poet-rocker’s feral, androgynous energy and sinew, an incongruity that is similarly heightened by the Mapplethorpe photos of the musician, as thin and lethal as a blade, that flash onscreen. Another victim of bad bewigging, John Benjamin Hickey portrays Sam Wagstaff—a patrician silver fox IRL, who succumbed to AIDS-related pneumonia two years before Mapplethorpe died—with all the charisma of a Dockers dad. A scene of their postcoital chat, cut to immediately after Mapplethorpe and Wagstaff flirt hard in an elevator following the older guy’s visit to the younger one’s studio, typifies the movie’s reliance on facile eureka moments and telegraphing dialogue. (As for that coy edit, from pickup line to rumpled sheets: it’s funny how a film about a paladin of man-on-man action should show so little of it.) Wagstaff proudly displays to his bedmate two of his prized pieces, Hippolyte Flandrin’s 1835–36 painting Nude Youth Sitting by the Sea and Wilhelm von Gloeden’s circa 1902 photograph Caino, both key predecessors to Mapplethorpe’s 1981 Ajitto series. “Wow. I like that. I like the shape,” Robert says of the naked figures in each, their knees pulled to the chest and their heads bowed. And after asking Wagstaff, born a quarter century before Mapplethorpe, his age, the photographer pauses for a beat before responding, “I’ll never know what it’s like to be fifty.”

Matt Smith as Robert Mapplethorpe in Mapplethorpe. Image courtesy Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Despite the multiple biopic banalities—and somewhat surprisingly, given the Mapplethorpe Foundation’s involvement—Timoner’s movie isn’t shy about depicting its subject’s voracious desire for fame (“Hustler-hustler-hustler. I guess that’s what I’m about,” Patti quotes Robert as saying in Just Kids) or his crude hypersexualizing of several of his black male models. And images too hot for the Guggenheim exhibition (which I took in a few hours before seeing Mapplethorpe), such as the infamous shot of anal fisting, are given more than a cursory glance here, when the artist’s younger brother and soon-to-be assistant Edward (Brandon Sklenar) tremulously looks through his sibling’s X Portfolio.

Yet ultimately the movie, with its gimcrack period pageantry, cannot escape its essential conundrum: that it is subordinate, inferior to the still images that festoon it. By Mapplethorpe’s end, I wondered whether Timoner’s feature was perversely arguing for its own dispensability. Lying in a hospital bed, Matt Smith/the photographer looks directly at the audience and delivers the film’s final words: Take the picture. It sounds less like a command to aim and shoot than sage advice, a prescription for one medium over the other.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.