Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

An unflinching documentary from 1993 follows a male couple as they struggle against AIDS and stigma.

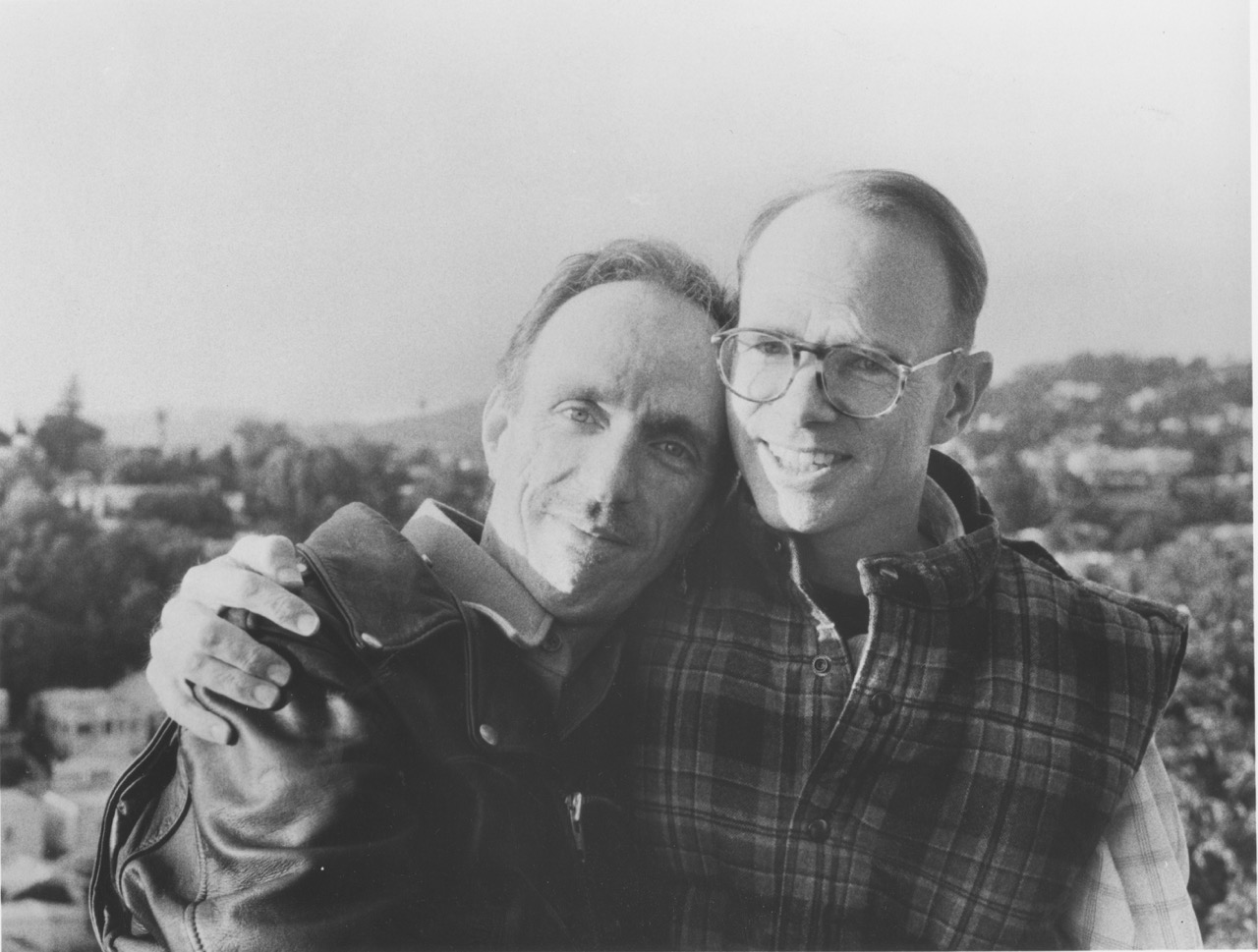

Still from Silverlake Life. Image courtesy Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Silverlake Life: The View from Here, directed by Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman, screening February 25, 2018, Walter Reade Theater, 165 West Sixty-Fifth Street, New York City

• • •

On June 15, 1993, PBS broadcast Silverlake Life: The View from Here, a raw, unflinching video diary of two gay men, Tom Joslin and Mark Massi, lovers for more than two decades, who are both dying of AIDS. Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival that January, the documentary, directed by Joslin and Peter Friedman—who completed the project after Joslin’s death—aired during a year that brought more grim news about the pandemic: patients with the disease started to show resistance to AZT, then the principal drug used to treat HIV/AIDS. Silverlake Life was televised five months into the presidency of Bill Clinton, a putative progressive who nevertheless signed two virulently homophobic policies into law during his first term (“don’t ask, don’t tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act). Adding further to the dissonance—cultural, political, sexual—of the era, six months after the broadcast of Silverlake Life, Jonathan Demme’s Oscar-feted movie Philadelphia was released in theaters, a decorous, desexed AIDS weepie that is the antithesis of Joslin and Friedman’s urgent, intimate chronicle.

A homosexual Gen-Xer then living in Washington, DC, I vividly recall the Tuesday night from a quarter-century ago that I watched Silverlake Life. Yet it’s not the details of my ineradicable viewing experience I want to share, but the observations of another admirer of the film, Robin Campillo, the French director and co-writer of last year’s BPM (Beats per Minute), a pulsating drama about the Paris branch of ACT UP set in the early 1990s. In an interview for Film Comment’s blog last October, Campillo, who joined ACT UP–Paris in 1992, spoke about the influence of Silverlake Life on his own movie: “I was thinking of this film, because for me, it’s a film which is so strong about the disease. But I didn’t want to represent the disease too much, because I thought it was so real in Silverlake Life. It’s a documentary, not a fiction. I didn’t want to make the same thing because you can’t do more than this film . . .”

Perhaps Campillo’s praise for a documentary that, despite its initial importance and impact, has faded from memory over the past twenty-five years inspired the organizers of the annual showcase “Film Comment Selects,” running February 23–27, to include Silverlake Life in the lineup. It’s a key artifact from the wretched epoch when a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS instantly equated pariah status, and whether you’re seeing the film for the first time or anew, the experience is gutting. Much in the same way that BPM vivifies the kinetic might of ACT UP—called “the last of the great new social movements of the 20th century” by one of the group’s vets—Silverlake Life makes overwhelmingly powerful a simple act undertaken by two men: to bear witness to their own rapidly decaying bodies. The endeavor stands as a testament not only to their devotion to each other, but to their determination to destigmatize their very existence.

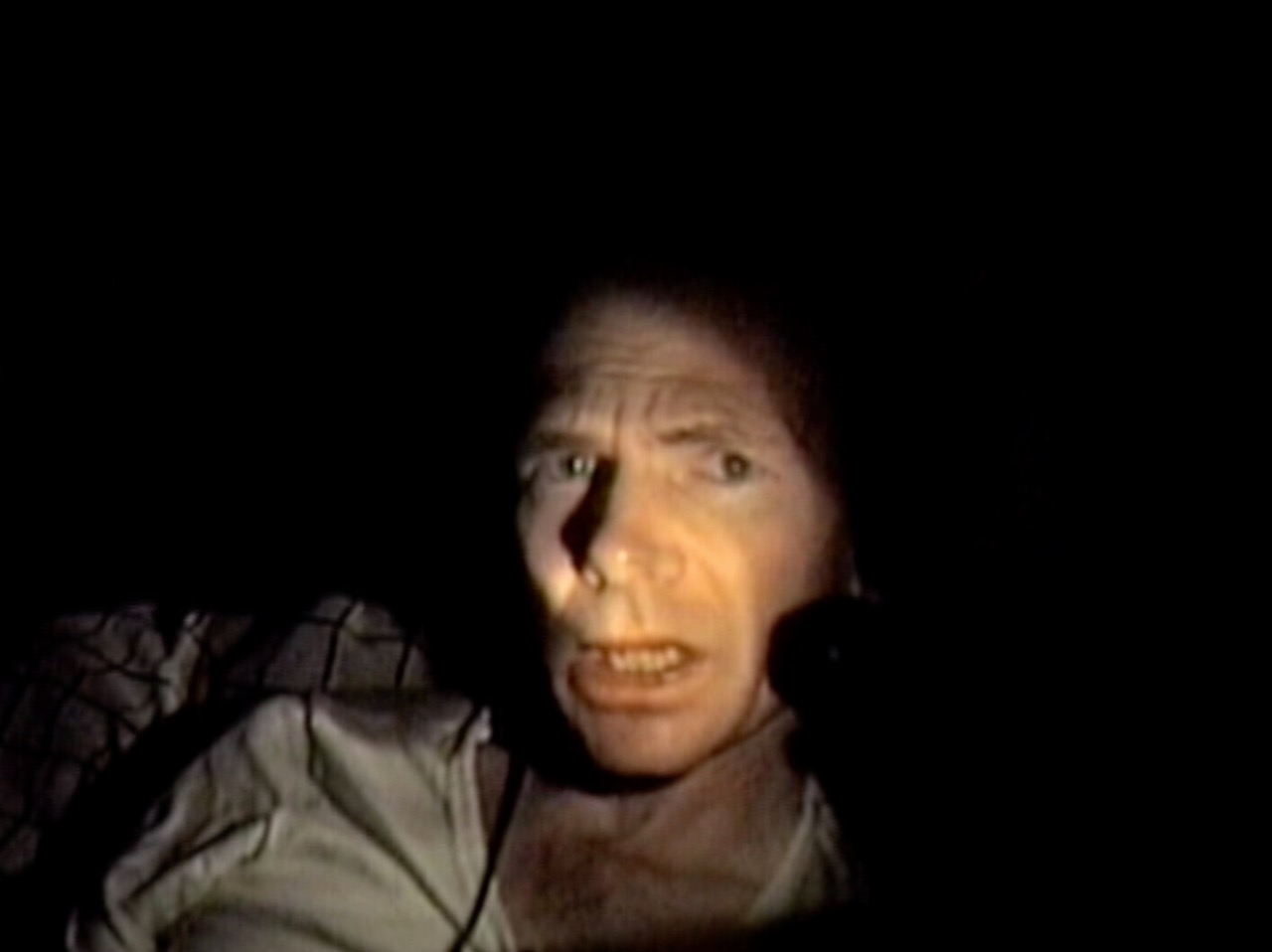

Still from Silverlake Life. Image courtesy Peter Friedman.

Silverlake Life, the title a salute to the gay neighborhood in Los Angeles where Joslin and Massi had been living, begins achronologically. Massi—ginger-haired, goateed, skeletal, with KS lesions visible on his neck, face, and arms—speaks into the camera after the documentary’s defining event: the death of his boyfriend of twenty-two years. The very recent widower recounts to Friedman (who, as he explains in introductory voice-over, was a student of Joslin’s in the mid-1970s at Hampshire College) his effort to close his lover’s eyes just after Joslin’s demise. Massi is alarmed to discover that the eyelids, contrary to what countless films have shown us, don’t stay shut. “I apologized [to Tom] that life wasn’t like the movies,” says Massi, who, appositely, is wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the title of a 1985 box-office hit: Cocoon, about a group of scofflaw seniors rejuvenated by aliens. (Massi died in 1991, the year after Joslin.)

Still from Silverlake Life. Image courtesy Peter Friedman.

Life wasn’t—isn’t—like the movies, but Joslin had for decades been committed to making movies of his life, a radical notion for a gay man born in 1946. Interspersed throughout Silverlake Life, which records Joslin and Massi at home, at doctor’s visits, running errands, and traveling before Joslin becomes completely bedridden, is footage of an earlier cine-memoir by Joslin: Blackstar: Autobiography of a Close Friend, completed in 1976 (and easily found online, at no cost). Massi features prominently in the earlier film, too—by ’76 he and Joslin were already several years into their long union—evincing the ardor for (and occasional exasperation with) Joslin that would remain undimmed by the time of Silverlake Life. (Contemporaneous with and complementary to Blackstar is the revelatory documentary Word Is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives, featuring twenty-six men and women forthrightly discussing the perils and joys of being queer. The film, which premiered in 1977, was made by a collective whose members included Rob Epstein, another student of Joslin’s at Hampshire College. Epstein would go on to direct other significant LGBTQ nonfiction movies, such as The Times of Harvey Milk, from 1984.)

Near the end of Blackstar, a project made less than a decade after Stonewall, Joslin, standing in a snowy patch of land not too far from the New England house he grew up in, notes that deception and evasion were survival skills that gay people learned early. “I don’t want to lie anymore. So I make this film,” he declares. That same conviction permeates Silverlake Life, which neither spares the viewer the physical agony he and Massi endured nor hides the simple pleasures that buoyed them. The most quotidian acts—going to a record store, enjoying a slice at Hard Times Pizza—register as heroic feats. Joslin’s camcorder went everywhere, including to a couples counseling session, during which Joslin confesses, “There’s a certain amount of desperation in relation to this kind of thing—the videotaping.” Silverlake Life is a project born of desperate times. The documentary’s subtitle—“The View from Here”—anchors the film to a specific moment and place. “Here” has become “there and then.” The view—courageous, shattering, stirring—remains the same.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. From November 2015 until September 2017, she was the senior film critic for the Village Voice. She is a frequent contributor to Artforum and Bookforum.